In the latest edition of our award-winning interview series, we decode how an accountant at Delhi's Le Meridien hotel became one of India's most loved filmmakers

Shoojit Sircar. Pic/Sameer Markande

But you’re not like this [as a person],” an assistant on the sets of Sardar Udham exclaimed to filmmaker Shoojit Sircar — observing him seated, with two buckets full of fake blood, getting constantly replenished on either side of his feet.

But you’re not like this [as a person],” an assistant on the sets of Sardar Udham exclaimed to filmmaker Shoojit Sircar — observing him seated, with two buckets full of fake blood, getting constantly replenished on either side of his feet.

ADVERTISEMENT

He would dip into it with a mug, splashing that blood to dry earth himself, to get the colour right — all the while operating the camera, filming the Jallianwala Bagh sequence in Sardar Udham (2021).

It’s gory as hell. But Sircar wanted to get April 13, 1919, just right. Martial law in Punjab. Curfew in place. No one allowed to help the injured and dead. One man dealing with dead bodies after dead bodies.

Shoojit Sircar joins Hitlist editor Mayank Shekhar for the first in-person edition of Sit With Hitlist post the pandemic

Shoojit Sircar joins Hitlist editor Mayank Shekhar for the first in-person edition of Sit With Hitlist post the pandemic

It’s a scene Sircar had been living with, ever since he first visited the actual Jallianwala Bagh site in 1998 — much before he’d even thought of becoming a filmmaker. He’d been going back to that sequestered memorial park, through a narrow passage to the entrance in Amritsar, every year since. It’s a walk down from Golden Temple.

Watch the entire interview here:

This was his only chance to recreate what he believes was the turning point of India’s freedom movement — the massacre of thousands of people, peacefully protesting the draconian Rowlatt Act, that allowed the British government to incarcerate Indians, without proper trial, under the pretext of ‘national security’: “It gave birth to many unsung revolutionaries, of which we only know about Bhagat Singh, and now Sardar Udham.”

It took Sircar four months to get the colour of blood right. Real blood for shoots is usually imported. They didn’t have the budgets. Jallianwala Bagh is also kinda immortalised from Gandhi (1982), by Richard Attenborough, who had resources to bring down train loads of people from Punjab, to shoot the short scene in Delhi.

Sircar had to shoot in Punjab itself, to get the look of thousands of actors/extras right. He hired locals. Some of them were children trained in Gatka style of martial art. They’d do free-falls and heavy-duty acrobatics, although they’d never faced a camera before.

On day one, actor Vicky Kaushal was his usual enthusiastic self. But as the shoot progressed, with humans being carried like carcasses in wooden carts, and the smell of fake blood and dust around, the cast and crew started getting affected.

Once, when the shooting had packed up for the day, a young girl was still around, that the assistants insisted they should shoot with, anyway. Sircar decided to casually pick the scene, knowing they didn’t need more. Soon as the girl started crying for her mother (in the scene), Kaushal began uncontrollably howling as well. The girl was a little flummoxed. They kept the camera rolling from a distance, most of which made it to the final film.

Deepika Padukone and Amitabh Bachchan in Piku (2015)

Deepika Padukone and Amitabh Bachchan in Piku (2015)

Every moment in the Jallianwala Bagh scene, step by step, Sircar says, is mentioned in Hunter Commission and the Congress report, besides survivor statements of ladies named Ratan Devi and Attar Kaur. It lasts a lifetime in Sardar Udham: “I have not left any single shot in my edit room. Everything is used.”

Some might dub this as an over-indulgence of sorts. It will remain etched as one of the most haunting sequences in Hindi cinema still. Unsurprisingly we talk about it for a good portion in this conversation. Only as a nod of sorts for the fact that Sircar filmed this one sequence, over 21 days in Punjab!

Sardar Udham is essentially a London-based period film, for which Sircar extensively referenced series such as Peaky Blinders and The Crown to get the era right.

Sircar with Vicky Kaushal on set of Sardar Udham

Sircar with Vicky Kaushal on set of Sardar Udham

As for a wider inspiration, while there is no direct connection, Sircar calls Sardar Udham “a tribute to Akira Kurosawa’s relatively lesser known film, The Hunters, set in Siberia, filmed as a Japanese-Russian collaboration.”

Which makes me segue into his film company, Rising Sun. Is that a reference to Japan? “Well, we didn’t think about it. My producer Ronnie [Lahiri] suggested Rising Sun. It sounded positive. I asked him to check if there is any other Rising Sun Films. There wasn’t, so went ahead!”

I ask this because over a decade and half, while the eclectic Sircar undoubtedly has belonged to commercial Bollywood, he remains essentially an independent filmmaker, which is an anomaly of sorts.

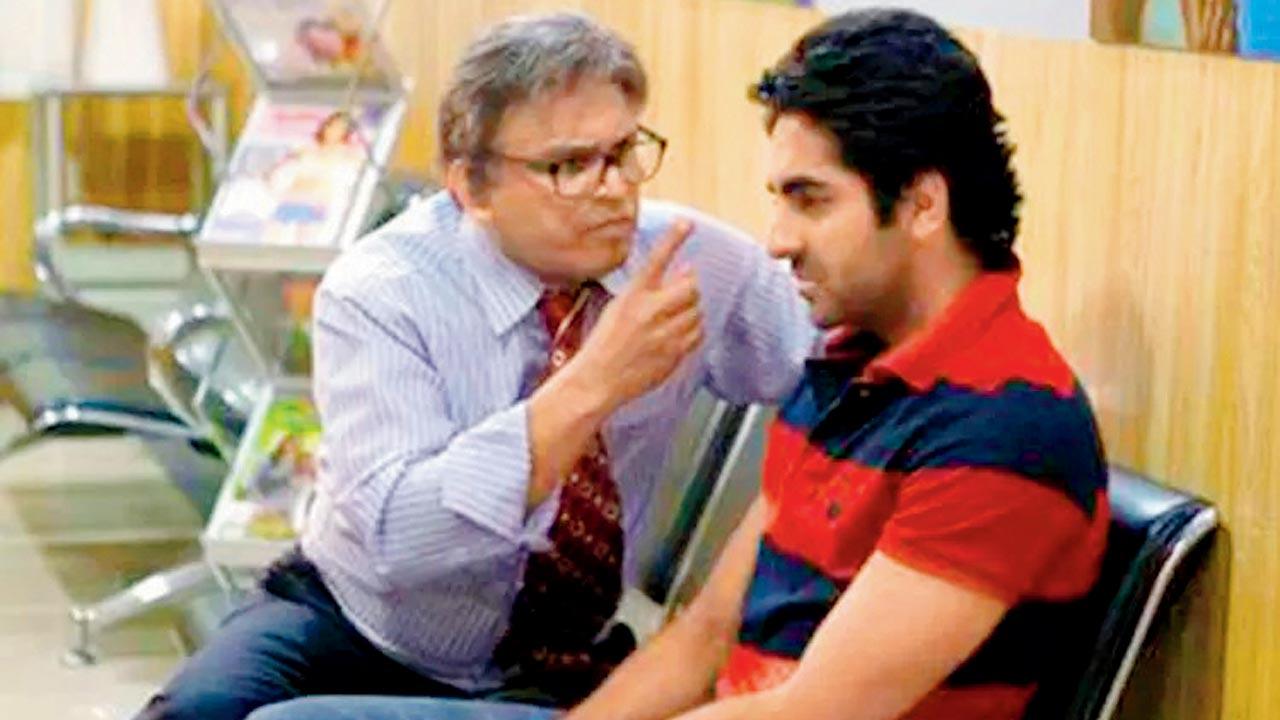

Annu Kapoor and Ayushmann Khurrana in Vicky Donor

Annu Kapoor and Ayushmann Khurrana in Vicky Donor

Throughout, he has teamed with the same producers, Goa-based Lahiri originally from Shillong, and Bihar-born, Russian educated Sheel Kumar, taking care of the finances. Besides more or less the same crew of writers (Shubhendu Bhattacharya, Juhi Chaturvedi), cinematographer (Avik Mukhopadhyay), editor (Chandrashekhar Prajapati), and the like.

He says, “[By independence], you [mean to] do a film on your own terms. Of course, we compromise sometimes. And I have been compromising [as well]. But film after film, I have reduced that.

Also Read: Sit With Hitlist: How not to be the ‘minimum guys’

Crafting your own path is a lesson I have learnt from the city [Bombay] itself, and its film industry. Otherwise, nobody will let you be what you are — forcing on to you what works. And in cinema, there is nothing like, ‘what works’ — it is an expression. You do what you are compelled to, from the inside — what you feel like; you do that.”

Which explains how the money being thrown at him to script a sequel to Vicky Donor (2012) is pretty much the budget of an entire film — he doesn’t reveal the number — but he won’t click that bait, simply because Vicky Donor is behind him, and he’s “not that filmmaker anymore.”

The auction is only natural, given that a Rs 4.5 crore Vicky Donor — a slice-of-life comedy on sperm donation, that even Sircar hadn’t imagined would capture an audience beyond those interested in quirky movies — picked up close to R80 crore at the box-office! This equals ‘family audience’ in Bollywood speak.

Debutant Ayushmann Khurrana was the star. Which also opened up a minor film industry for Khurrana headlining a series of comedies on similarly taboo subjects — balding, old mother pregnant, gay love, etc.

With Sircar, these benefits can be a challenge: “I am actually very scared of the wrong audience, and unnecessary hope. I am openly telling you — with Gulabo Sitabo (2020), I faced so much of that. I was doing a film with Amitabh Bachchan and Ayushmann Khurrana. So people think it is Vicky Donor and Piku coming together!

I faced so much flak after [Gulabo Sitabo came out] — this film is so slow, nothing happens… But that is what I had made. I wasn’t thinking [Vicky Donor and Piku] in my head. Don’t expect it. Yet, how do I convey that? It is so difficult. So sometimes, wrong audiences can really harm your film!”

To be fair, Sircar has dabbled in multiple genres, without getting overwhelmed by the success of his previous work. In fact, if you notice, he consciously shifts from light-hearted to serious subjects/treatments — say, a political thriller Madras Café, after Vicky Donor; a strikingly sombre October, after Piku. It’s something he describes as mere coincidence. Rather than an effort to alter his mind space.

Shoojit Sircar wielding the camera during shoot

Shoojit Sircar wielding the camera during shoot

“A movie is not like a mask, that you take off after it’s over, and put on another. It stays inside you forever. I am Sardar Udham. I strongly feel about it. I strongly feel about greed in Gulabo Sitabo. I feel for October, because I have been in ICU for three months with my mother. And I know exactly what happens [being around] a comatose patient. I cannot just throw it away.”

Sircar debuted as a feature filmmaker with Yahaan (2005), set in Kashmir, about a local girl and an Army officer, during the height of insurgency/militancy. One of the aspects that stood out in that film was its coolly lit bluish tint, lending a surreal touch to the screen, although the film was shot on actual locations.

Also Read: Sit with Hitlist: Farhan from the madding crowd

I am wondering of this level of visual sophistry had much to do with his work in advertising, which is how he first got into films. Sircar says, if anything, his works are often more informed by documentary filmmaking, which is also what he dabbled in for close to five years before.

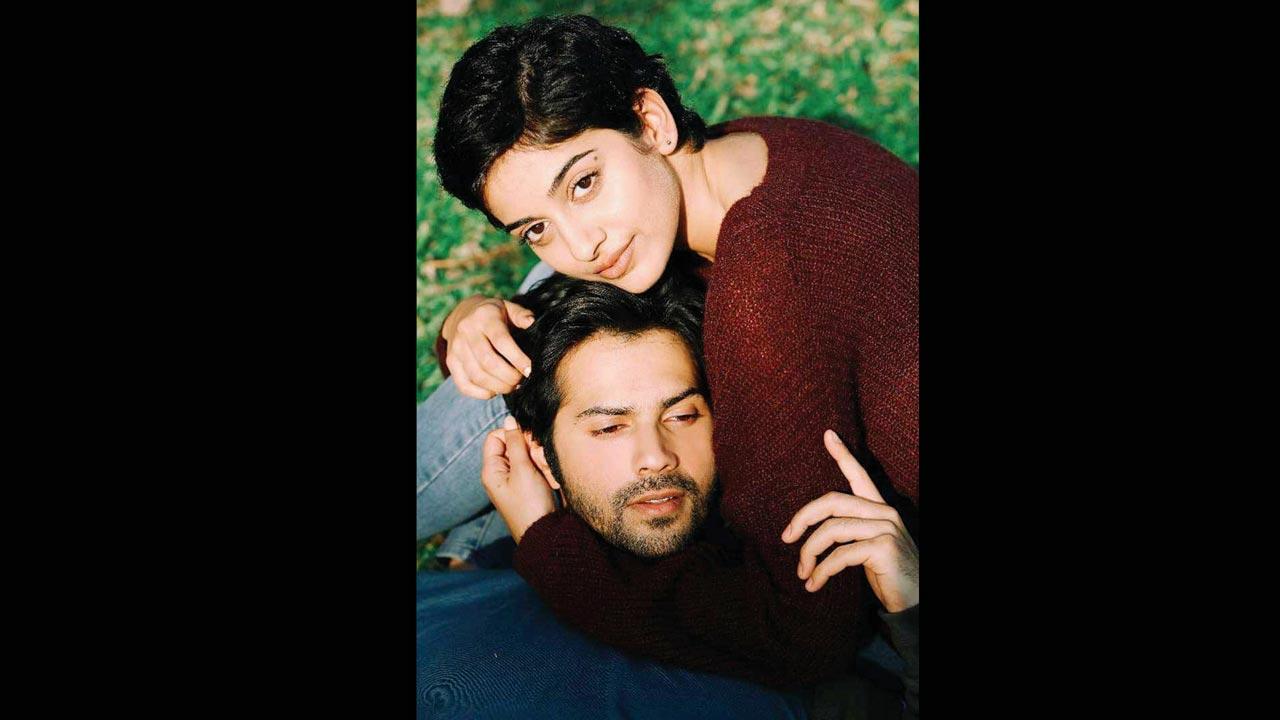

Banita Sandhu and Varun Dhawan in October (2018)

Banita Sandhu and Varun Dhawan in October (2018)

Yahaan was also the debut feature film of Swedish cinematographer Jakob Ihre. What’s Ihre best known now for? Shooting the stunning HBO series, Chernobyl. Yup! “Jakob was once in Delhi to shoot a documentary for BBC4. A friend of mine was the sound person for the film, who introduced us. Of course I knew of the Polish film school he was from, which is really good. I did a commercial with him, which was also done on my own terms. The ad was for toughened glass.

But the film, for around three minutes, unheard of at the time, was all about reflections. With Yahaan, I was wondering if I would get Kashmir right — I had done a documentary there, and knew what Charar-i-Sharief or Habba Kadal Bridge will look like.

I needed a different perspective. The first thing Jakob told me when I took him to Kashmir is it looks like Bosnia, which also had problems going on at the time. In winters, Kashmir, like Bosnia, is brown and silver. Jakob got onboard and shot Yahaan.”

They’ve been friends since. The script of Yahaan “bounced like a ping pong ball” between all the corporate studios in Mumbai, until Sircar first went ahead with it himself, with Jimmy Sheirgill and Minissha Lamba in the lead roles.

Ad films have also allowed Sircar financial independence, and some flex to make only the features he wants. It also turned him into a patron of the arts early on, in the early ’90s, while he worked in an amateur theatre group Act One in Delhi: “I was a mole from my [theatre] group in the advertising industry. I’d make money from ads, and whatever I’d earn, I’d put into theatre. That is what my job with the group was — you make the money, bring it to us, and we will do plays!”

Act One had performers like Manoj Bajpayee, Gajraj Rao, Piyush Mishra, among others, who later moved to movies and Mumbai. Sircar continued in advertising, mitigating the struggle that involves, in hindsight, romanticised notions of stepping into showbiz city, with few rupees in wallet, friends with culinary benefits, and sleepless nights in railway platforms. Sircar has none of those heartbreaking stories of following a personal passion.

In fact, strangely enough for a Bengali, the arts, cinema, and literature were totally external to his growing up years. Football was his life’s primary goal; something he actively pursues at 53 still.

Graduating in commerce from Delhi’s Bhagat Singh College, Sircar was quite comfortably placed as an accountant in one of the city’s top hotels, Le Meridien. Which is a longish walk down from the Capital’s cultural district, that houses National School of Drama, and several theatre performance spaces.

Almost like a turning point of a movie script, a moment of epiphany as it were, Sircar’s friend [his writer now] Shubhendu Bhattacharya asked him once to step out to watch a play, after lunch, during work hours.

That was Satyadev Dubey’s production Andha Yug, written by Dharamvir Bharti, starring Naseeruddin Shah, Amrish Puri, Rohini Hattangadi. He says something happened to him once he watched that 3 pm show. There were no tickets available for the following 6 pm show, but he bribed the guard to enter again. By 9 pm, when he walked back to his office, he had “turned into a zombie.”

Following week, he watched Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali at India International Film Festival in Delhi’s Siri Fort auditorium. A film he had repeatedly slept through, during growing up years. The penny had dropped: “Then I started reading and watching with a different eye.” He joined theatre, then ads, thinking little of the debit and credit accounting of such a call.

Which takes us back a little to the film October (2018), one of his most personal works, since as he said, it came from the experience of nursing his mother in an ICU ward. But its setting — the full expanse with doors that demarcate the contrasting inside and outside world of a five-star hotel is clearly from his time from Le Meridien?

“When [writer] Juhi bounced off the structure, character and idea about how the film would be, it clicked: ‘Okay, hotel — I know hotel, so I will go into this’. I had no problem in understanding the hotel. My art team said we will create it. I said, no, you cannot create this. It has to be real.”

As is the story — emotive, seeping through the pores, at every level. Even if there’s a touch and feel of Sircar in the lead character, Dan, the fact is, if you rewind to when the film was being planned, the last person you’re likely to imagine in the lead role is the boisterous Varun Dhawan — of ‘tera dhyan kidhar hai, tera hero idhar hai’ fame! There has to be a story behind Dhawan breaching a likely mental/casting block. There is.

Sircar recalls, “Varun had been calling to meet me for quite some time. I live in Kolkata, and would be in Mumbai for two days and leave, so I wasn’t getting time. Once when I had a flight to catch, I saw his text, “Dada, when is your next?” I told him that I was in town, but leaving in a bit.

He said his house was close by. I asked him to quickly drop in. He said he’ll take a shower and come, and that he’d just woken up. I told him nobody will see him: ‘Just walk in as you are’.

I still have his picture from that day — he was clumsy, holding a bottle that fell. He said, ‘Sorry, Dada, sorry.’ While talking, he zoned out completely. I don’t know what he was talking to me about.

[As an actor], he wasn’t on my radar at all. I looked at his torn jeans. He said, please, don’t look there. He just sat there, said, ‘Theek hai, Dada.’ And left. In the flight I kept thinking about him. As I landed, I called up [writer] Juhi and [producer] Ronnie. This is what the clueless Dan is, you know — he doesn’t know what he’s doing, saying, where he is…”

The unlearning of the Bollywood star started before shoot. For script, Sircar only shared the first half of the film. For prep, Sircar passed on a piece of meditation music to Dhawan and asked him to simply stare at a house-plant every morning with it!

“On the first day, we shot the film’s last day’s conversation with the girl — it’s an important scene. I thought I’ll catch him raw, the way I had caught him in the office that day. He said, ‘Dada I am not doing anything [in the scene]’. We rolled the cameras in the rehearsal take, and used it in the film.”

It’s a little like how Sircar got Ayushmann Khurrana into the infamous sperm donation scene in Vicky Donor. Khurrana had to go to a private room to donate sperm.

Except, there were no instructions on paper about what he’s supposed to do. There were CCTV cameras placed in the room. Khurrana was clueless. He got out of the room and said, “Aise thodi hota hai? (What am I supposed to do; this is not how it happens!” The cameras captured that actual line.

In Dhawan’s case of course, the idea was to keep him slightly clueless all through the shoot, instead — something the camera captures convincingly in October.

As for another unlikely casting, the one that comes to mind is John Abraham. Abraham incidentally won the National Award for Vicky Donor—as the film’s co-producer. No knock on Abraham. But he isn’t quite the first actor one might have in mind for Sircar’s reasonably intellectual political thriller, Madras Café. It was a deeply researched procedural on the plot to assassinate Rajiv Gandhi, called “the PM” in the picture.

Sircar admits, “You can say Madras Café was one film that I just quickly wanted to make. By 2010, the entire Tamil group [LTTE] had been wiped off. The [assassination] case was completely shut.

I just thought I must go ahead and make this [before it’s too late]. I didn’t wait too long. The research and script were quite good. In terms of my craft around making the film, I would do it completely differently now, and with an absolutely fresh mind. It could have been much more powerful. That’s one film I would really want to go back, and remake.”

What would he do differently, in particular? “Of course, I will take real names [of characters], as I did with Sardar Udham. I’ll go with a completely new set of cast. There are many places where I have compromised, in terms of dialogue. Then there is the heroism part of the film. My idea of heroism has changed, from then and now. For me, heroism is not about [being a] hero [type]. For me, heroism is doing the right thing — rather than not. That is what it is.”

That’s of course a film yet to be seen, but from what we have of Madras Café, as it exists, it is by no means even vaguely a low point in Sircar’s career — wonderfully farmed from the Jain Commission Report, it survives as an important, albeit slightly over-the-top document, detailing the assassination of PM Rajiv Gandhi.

If at all, the cursory low point in Sircar’s career might well be a film of his that we haven’t seen. And that’s because it never got released—Shoebite, the director’s first collaboration with Amitabh Bachchan. From my memory of what went wrong with the film was a dispute between two companies, Percept and UTV. The former were first producing the film.

There was a hitch over Bachchan’s remuneration, reportedly. Percept brought on board Anil Kapoor for the lead part instead. Sircar and Bachchan jumped ship together, bringing in UTV to produce the film instead. Copyright issues followed. I needlessly jog my memory for Sircar, who is understandably not so forthcoming on this.

“Well, it’s a long story. But I can tell you where we are now, I think. So, finally, the film is with Disney. And Disney is also Fox, and Disney is also UTV. They can actually release the film. They are still figuring it out. What’s happened in the past is over.”

The Fox angle in the story could have to do with the original concept of Shoebite being Hollywood filmmaker M Night Shyamalan’s. Is that true? “So, the script was adapted by Rensil [D’Silva], who had just done Rang De Basanti. Later we found out that this was an idea by Manoj Night Shyamalan. I stepped back. Then Ronnie Screwvala [UTV boss then] was doing a film with Shyamalan and [our project] restarted. Since the basic idea was written by Shyamalan for a Hollywood film, we requested for a regional version. It was messy. But it is quite sad that the film still in the cans. It should release.”

The other messy stuff that’s made it to print in the past, so far as Sircar is concerned, are cases registered by writers against two of his films, Gulabo Sitabo and October, over copyright infringement. Much talked about before release, allegations hurled, press lapping up.

“It is distressing. When it happened with October (a Marathi filmmaker alleging rip-off), I was completely shaken up. We thought we were creating something absolutely fresh, and new, and everything had come out from my own deepest experiences, and Juhi’s as well. Same with Gulabo Sitabo. This is no way. Tons of stories can stem out of landlords and tenants. But after the film [releases], there is nothing. After the film is gone, there’s nothing.

The entire panel of writers’ association has seen the film, and given us a clean chit. What else you can do? I was telling Ronnie the other day: I hope with Sardar Udham, nothing comes up. Ronnie told me I should get used to it. It will come, so it’s okay; be ready for it. It is distressing sometimes. We could not enjoy the release of October, because of this. Normally I go to the theatre and watch the film [with the audience]. We didn’t.”

Thankfully none of the above this has impacted his works consequently. Bachchan, for instance, was happy to sign up with Sircar, despite their first film together having been a non-starter. The released movie is Piku (2015), of course. The brief he gave to his writer (Chaturvedi) for it was long scenes; “sometimes 20 pages long.”

Sircar wanted to stage Piku as a play first — “experience from theatre really helped” — and then cut at the editing stage. The driving force being to test the acting styles of three really diverse performers—besides Bachchan, Irrfan and Deepika Padukone, whose subtly expressive eyes were really the leads as well.

Sircar reasons, “Mr. Bachchan, as a person, is all method—he will rehearse, and be so particular — you can’t use left-hand on the rehearsal, and right-hand on the take. You can’t. On the other hand, Irrfan is someone who just lets go. And he can go on. Deepika is natural. You have to tap into her internally, as an artiste.

My instruction was that in this film, nothing is happening, nothing is moving. It’s in the drawing room of a Bengali household. If you notice, there are a lot of silences in the film. And I want audiences to hate this Bengali family.

Irrfan, though, had just convinced himself that there will be a love angle to the story eventually: ‘You’ve cast me with Deepika, there will be conversations; of course we’ll get romantic’. I had to constantly explain to him that’s not going to happen. People will define [this relationship] in their

own way!”

It’s not like the actors didn’t have other apprehensions. Bachchan, for one, did. Until Sircar practically convinced him by actually enacting his part over a narration — after Big B had read the script, with long notes on side margins sent as feedback. While it doesn’t show, the soft-spoken Sircar does have a stubborn streak. It’s that same indie cinema spirit about working on one’s own terms.

When Piku released, Sircar says, it was being deemed as an altogether Bengali movie: “I said no, it’s a Hindi film.” Unsure why he had to be defensive, because Piku is indeed a Bengali film — so specific, that it’s universal enough.

With the added bonus that most Bengalis I’ve met have so identified with this family — of a cranky daughter, who’s had it with a loud unselfconscious, child-like dad, obsessed with his bowel movements — that they repeatedly watch Piku, as if it was their home video.

An air force officer’s son, Sircar grew up across defence establishments, given his father’s transferrable job. He spent a lot of time in Delhi. For home, he chose Calcutta still — far from Mumbai’s maddening movie crowd, that he occasionally returns to, for work, and disappears into the “17 football fields” around his Salt Lake, Kolkata address. He says this is also to root his two daughters into a local/Bengali culture — a privilege he didn’t enjoy himself.

But speaking to him for an hour and some, before a live audience, I sense this could be because Sircar, an ardent devotee of Satyajit Ray, is as genially Bengali as it gets. When it comes to the most special skill the community enjoys, no matter where they are in the world — ‘adda’, that long, warm conversation on things from here and there, that can carry on, even when the cameras are switched off. As was the case with this edition of Sit with Hitlist.

Shoojit Da would tell us a thing or two about good health — the importance of walking. Not brisk walk; just walking. And the right posture to hold a phone, which is not to hold it at all — 20 minutes of cellphone on palm plus wrist equals 17 kg burden on the shoulder. I’ll take that advice from a footballer, who can be quite the Dada on a field, dribbling much younger men like Ranbir Kapoor and Abhishek Bachchan into exhaustion.

He’s also happy to heckle on the field. Which isn’t my mental image of him, given the gentle demeanour. Equally unsurprised that his assistant was flummoxed looking at him going absolutely berserk with blood and gore, shooting the iconic Jallianwala Bagh sequence in Sardar Udham.

Also Read: Anurag Basu: Ranbir and I never fought on Jagga Jasoos

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!