One of India’s greatest filmmaking talents ever, polymath Bhardwaj, opens up on the man behind the movies

Vishal Bhardwaj. Pic/Ashish Raje

Gulzar-Vishal Bhardwaj's musical combo is top of the charts’ stuff. But Vishal’s first mentor, from the world of poetry was, in fact Dr Bashir Badr, whom he calls the “greatest poet of the century, an asset to [his hometown] Meerut,” who had to flee Meerut, however, because of the riots in 1984.

Gulzar-Vishal Bhardwaj's musical combo is top of the charts’ stuff. But Vishal’s first mentor, from the world of poetry was, in fact Dr Bashir Badr, whom he calls the “greatest poet of the century, an asset to [his hometown] Meerut,” who had to flee Meerut, however, because of the riots in 1984.

ADVERTISEMENT

Bashir Sahab had heard rumours of a likely attack on his house in Shastri Nagar. His home was indeed burnt down by a raging mob later.

In the rush that he fled for Bhopal, Bashir Sahab left behind his diary, with all his poetry, written over the past year. When he briefly revisited Meerut, he asked for two people—one, Mr Bhandari, who was 70 years old, and the other, Vishal, who was 19 then.

Vishal Bhardwaj with mid-day’s entertainment editor Mayank Shekhar. Pics/Aishwarya Deodhar, Ashish Raje

Vishal Bhardwaj with mid-day’s entertainment editor Mayank Shekhar. Pics/Aishwarya Deodhar, Ashish Raje

He asked both if they remembered the ghazals and his poetry from the destroyed diary. Bashir Sahab had gone into depression. Between the old man, Bhandari, and teenager, Vishal, they recalled all of the great poet’s works to him, word for word as he penned them back again: “This is how Bashir Sahab got out of depression.”

Vishal used to spend every evening, listening to Bashir Sahab’s words of the day. With poetry, he says he has a photographic memory: “At one point, I could recite the entire book of Gulzar.”

This Bashir Badr story I’d heard before, over drinks, with his former associates once. As is with such nights, I’d forgotten most of it the next morning.

Including details of the tragic events preceding Vishal’s father Ram Bhardwaj’s demise—which he recounted in detail, before a live audience, during this conversation. Only, a few weeks later, he sent in a word if that anecdote could be omitted. It’s about father and son. Too sensitive. We left it at that.

Earlier, he would cry, recalling the incident to do with his father’s death. But he says, “I found my catharsis in that scene in Haider [2014], when Shahid [Kapoor] returns to his home that’s burnt down, and he’s holding a cricket bat.”

The other story about Vishal that I have stored in my hazy memory, hanging with his former colleagues, is about how, as a kid in Meerut, he was caught in a crossfire, and he saw a dead gangster, right in front of him.

“Oh, those are actually two separate incidences,” Vishal says. “There was Tyagi Hostel in Meerut, where all these gangsters used to live. There was a wall, with a hole, between my school and the hostel. That’s the short-cut route we took to get to school. This is where the [chief] gangster used to live in the warden’s house. The warden used to live in the hostel!

“On my way, I would see him lay out and dry his bullets, guns, grenade, in the sun. The gangster was very fond of me and other kids. He would offer us to hold his gun, tease us with pulling the trigger.

“Once, during school exams, we heard gunshots fired. We went over to the gangster’s courtyard after. And he was lying dead, right there, with fresh blood, killed by cops, in a gang war! That’s the first time I saw a dead body. I was in Class VII, so must’ve been 12 or something.”

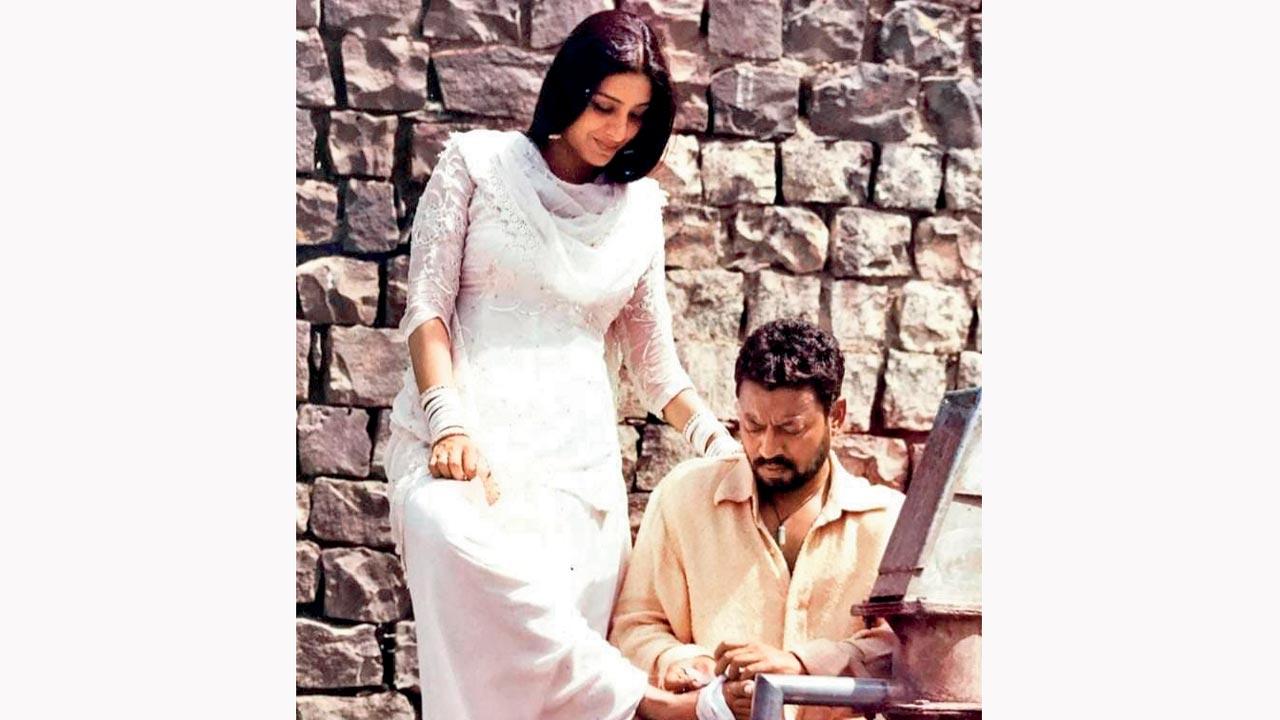

Maqbool, an adaptation of Macbeth, was Bhardwaj’s first film with Irrfan Khan

Maqbool, an adaptation of Macbeth, was Bhardwaj’s first film with Irrfan Khan

The other incident has to do with Hindu-Muslim riots, which Vishal says was common enough in Meerut: “But even then, the level of enmity [that we see now] didn’t exist.”

Vishal’s house was next to a Muslim family’s: “They had a large bungalow. The father was a learned gentleman. He had three daughters. My landlord was a police sub-inspector, with 10 children.

“Those kids decided ki hum Muslim kama lete hain, meaning score/kill Muslim people [during the riots]. That’s how it worked. I even heard them plan on going after one of the daughters.

Tabu in Khufiya

Tabu in Khufiya

“There was word from the police station that these boys had an hour [to do whatever they liked]—kama lo toh kama lo. That’s before the police would charge in.

“This is also how it worked. I knew about these boys’ plans. They had bought country-made pistols. They intended to enter the house, and blast the gas cylinder.

“The Muslim man inside had a Donali [double-barrelled gun] that he shot in the air. During what ensued, I got caught in the crossfire, and found my way out of it, into another house. My family got worried, because I had gone missing.”

Vivek Oberoi and Saif Ali Khan in Omkara

Vivek Oberoi and Saif Ali Khan in Omkara

This is when Vishal naturally pauses in the chat: “That’s the psyche of a mob. I have seen it. You ask an individual to kill another? They won’t. You get 50 people to do the same, without taking on guilt and moral responsibility? They will.

“This is why incidences like lynching and mob behaviour pain me. The support comes from the system.”

As with many great artistes, you only have to dig into Vishal’s past to figure what informs his life as a filmmaker and public figure too. Although pretty much all of his films, as a director, have been based on works of literature.

It might be fair to say, that’s only on paper. Consider his last feature, Khufiya (2023, on Netflix). It’s adapted from Amar Bhushan’s novel, An Escape to Nowhere.

I first read the book in 2013, basis a recommendation in Swapan Dasgupta’s column in The Times of India. Page for page, the film barely reflects the original text, which was more a survey of bureaucrats, fighting over foreign postings. Which is probably what R&AW really is, on a daily basis, anyway. Rather than Salman/SRK like James Bond agency, banging it in the killing fields.

Vishal says, “The book is a cold account of a surveillance operation. The detailing is so good. [Author] Amar Bhushan-ji was once the counter-espionage chief himself. Now, such a book is not even possible. Because the government has placed a ban. No officer can write such a book anymore.”

What about the leap of faith that he takes thereon from the book—surely, he had R&AW agents/officers vet the script, in case it seems too far-fetched? The original research, Vishal says, came from “seven to eight years spent”, working on a film based on the IC 814 hijacking (of 1999).

“I met Mr Ajit Doval [currently India’s national security adviser] several times. He had then retired [as the Intelligence Bureau chief]. Doval Sahab is a fascinating man, and a great storyteller!

“I also interacted extensively with ex-R&AW chiefs, Mr [AS] Dulat, Mr [CD] Sahay… Along with Mr [Vivek] Katju, the foreign secretary—these were the gentlemen chiefly negotiating with the hijackers. In any case, they really tell you what they want to. They might make you believe they’re answering your questions. But they’re not. It’s their point of view.”

Vishal’s film on the IC 814 hijack subsequently got shelved: “After the Tandav episode, Amazon Prime Video got paranoid. They pulled the plug on the project. They said they don’t want to touch anything political.

“The film actually had nothing to do with politics. The whole country was humiliated in that episode. It had nothing to do with a party. Now, Anubhav Sinha is making a series on it for Netflix.”

During the IC 814 homework, Vishal also met the IPS officer Arun Kumar, who was associated with the incident. In 2008, Arun became the first investigating officer from the CBI on the Aarushi-Hemraj Noida double-murder case (still unsolved, by the way).

Hence, Meghna Gulzar’s Talvar (2015), which Vishal produced and scripted, with precious/incisive details from Arun who, in turn, inspired late Irrfan’s character in the film.

Tabu, Vishal’s other muse, plays the lead in Khufiya, while the spy-thriller follows this R&AW sleuth’s story of love and loss with her Bangladeshi handler. None of which, of course, exists in the novel that the film is based on.

Citing his Shakespearean adaptations (Maqbool, Haider), to works of Ruskin Bond (The Blue Umbrella, Susanna’s Seven Husbands), Vishal says he’s essentially keen on the basic plot: “I have to know the drama I’m creating—and find a three-act structure, voice, characters, and my own politics and social environment in it.”

To illustrate this best, no better example than to go back to the aforementioned Tyagi Hostel, along with Meerut’s Kachehri Road, full of gangsters, Anand Shukla, Rampal Tyagi, et al. All of whom treated Vishal as their “blue-eyed boy.” Because he could sing and play cricket well. Watch them placed together in Omkara (2006), i.e. Othello. Shakespeare feels like an excuse.

One of the gangsters Vishal knew there was Langda Rathee, who got onscreen as Langda Tyagi. And that’s Saif Ali Khan, in what was easily the greatest casting-against-type for the decade. Vishal thanks Aamir Khan for this unusual choice.

Around the time, Aamir and him were zeroing in on a script, Mr Mehta & Mrs Singh, to work together: “Aamir was seeing the film a certain way. When we were close to the shoot of Mr Mehta & Mrs Singh, he was uncomfortable about how I was seeing the film.

“We are both headstrong people. We parted ways. But he’s great fun to spend time with, and during our chats, I told him about Langda Tyagi, the character I was writing.”

Aamir was fascinated by the world (of Omkara), and Langda Tyagi’s language, in particular, and wished to be considered for the part. He got busy with his next (Rang De Basanti).

Vishal was too eager to hit the set, rather than wait for Aamir, which would take long. But he realised, “Aamir is intelligent, and commercial. If this role can excite him, I’m sure it should excite another star.” Hence, Saif 2.0 (post Dil Chahta Hai).

There’s been was a similar hit-and-miss between Vishal and Shah Rukh Khan. They were to adapt Chetan Bhagat’s 2 States together (later filmed by Abhishek Varman on Arjun Kapoor, Alia Bhatt). What happened there?

Vishal says, “We had differences over the setting. I wanted to set the film in a bank like ICICI, and not in a college, or elsewhere, that Shah Rukh would’ve preferred. We felt the pain, though. I recently wished him for Jawan. Every time we meet, he repeats, we have to do a film together.”

While his sensibilities are innately artistic, it’s evidently clear, Vishal has throughout aimed for a spot in the mainstream, and achieved it, in his own right. He emphasises, “Maqbool [2004] opened the doors for me!”

◆ ◆ ◆

An apt way to introduce Vishal, as we did in this conversation, is as one of India’s greatest filmmaking talents, ever. There have been few polymaths with that many hyphenated top-end talents, within desi filmmaking—director, producer, music composer, singer, lyricist, writer of screenplays, and dialogues (often separate in Hindi cinema, because most don’t hold an equal command over language).

Vishal writes dialogues in pen on A4 sheets. But gets confused with his own handwriting later. One thing he misses his former associate Abhishek Chaubey (Ishqiya, Udta Punjab) for is deciphering what he’s written. Now, he has to figure it out himself. The instructions on the screenplay he keys directly into the computer.

The greatest polymath of all in Bombay was probably Kishore Kumar who, Vishal tells me, he shares his birthday with (August 4)!

But much before all of the above, Vishal was an “all-rounder” cricketer once—batter, and right-arm spinner—with an eye on international cricket. Former Test player Gursharan Singh spotted him in a match in Meerut, and suggested he move to Delhi. Which is the reason he did.

“I couldn’t have made it to the Indian team from UP. It was too big a state then [Uttarakhand hadn’t been bifurcated]. The facilities weren’t up to the mark. And the UP team barely made it up the chain in the Ranji Trophy. So, I would have never got noticed.”

In Delhi, he played with the likes of Manoj Prabhakar, Maninder Singh, Sunil Walson, Tilak Raj (who Ravi Shastri hit for six sixes), Chetan Sharma… Speaking of the latter, did Vishal whack Chetan out of the park, ever? “Yeah, I did.” That’s one thing he has in common with Javed Miandad!

Reminiscing those times is a lot like, as Vishal quotes Ghalib: “Yun hota toh kya hota!” Dealing in ‘counter-factuals’: “I came to Delhi. Right before the match, I broke my thumb. Couldn’t play the whole year. Next year, my father died. If cricket hadn’t left me, though—how would I have been in music, or the movies then? This world has no retirement age!

“Since then, I’ve learnt that if something unlucky happens to me—a greater reward awaits. I feel bad, of course, when something happens. But I don’t get disappointed.” From an early age, Vishal used to dabble in musical instruments lying around. Music was internal to his home.

Although with a day-job, Vishal’s father Ram—“everyone called him Ram Sahab”—was a lyricist in Bollywood. He would often visit Bombay, from Meerut, with family.

This is when Vishal spent time with film/music folk in Bollywood. On one such evening, his dad mentioned to his friends about how Vishal, “around 18 then”, had composed a short tune over his father’s lyrics.

His dad’s friends were hugely impressed. They got composer Usha Khanna on the phone to hear it. Usha loved it enough to include it in the final

composition.

“That someone like Usha-ji took my tune to expand into a whole song gave me my first validation. That validation gave me confidence.” The song, Khuda dosti ko nazar na lage, is from the film, Yaar Kasam (1985). At 19, Vishal recorded his first composition. Asha Bhosle was on the microphone.

After college in Delhi, he moved to Bombay with a job at a music label to pursue music, professionally. Vishal also had a brother, Rajeev, seven years elder to him, in Bombay—struggling to make it in films as a producer: “He had no money. But he wanted to produce movies. How do you?”

Rajeev passed away early. Decades later, Vishal became a formidable producer in Bollywood. I wonder if he feels, in some ways, it’s the story of two siblings coming full circle? He just wishes his brother was around to see it.

Filmmaking itself was an invisible milestone in his head, he says. “I had no intentions. I had seen nothing. Manmohan Desai to Blue Lagoon [for the sex scenes] was the range of my film knowledge!”

It was during the making of Maachis (1996) that he was composing music for, Vishal recalls, “Gulzar Sahab told me, I’ll become a director in five years. He actually pushed me into it. I used to ask him too many questions during the filming, editing…” The children’s film Makdee (2002) marked Vishal’s directorial debut.

Given he was a musician first, isn’t it strange that he’s never attempted a proper musical in films? He reasons, “In my earlier movies like Omkara, Maqbool, I did have actors lip-sync to songs. Because I also wanted to retain my power as a composer.

“With time, the purity of cinema took over. How do you then justify lip-syncing? The background score is the director’s voice. Anyway, India has a long tradition of cinema and music. Even if I do a musical, it would have to be on a subject that is totally non-musical.”

By the looks of it, his current obsession may be mystery/thrillers. After Khufiya on Netflix, his series Charlie Chopra & the Mystery of Solang Valley, based on Agatha Christie’s The Sittaford Mystery, dropped on SonyLIV. Which, he says, happened primarily because of the pandemic.

“The world was under lockdown. I was convinced we were in it for five to 10 years, or perhaps forever. How does one survive creatively for that long?

“Many years ago, I had been offered Agatha Christie’s entire library of Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple titles to adapt. Well, this is what we could do, I thought—shooting in constrained settings [during a pandemic]. I got back to the person, who had connected with me back then.”

What does he find in common between films and music, I ask Vishal. He says, “That they both work on the three-act structure, inspired from life, of course—bachpan, jawani, budhapa [childhood, youth, old age].

“Also, like with films, we don’t know what works in music. It cannot be calculatedly recreated, even though there are really seven notes.”

How about films and cricket—what does he find similar between the two: “Captainship. That you take along a team, especially when things aren’t going right. And they seldom do.

“Also, to accept defeat gracefully, and learn from the defeat.” Are there instances from his films that he’s learnt from, in terms of failure?

“It would be on the technical aspects. Take Rangoon [2017]. The release date was set. But we were not getting the VFX for the final scene right.

“I should have put my foot down. Held the release, like Sanjay Leela Bhansali does. I was making a Rs 70 crore film in a R35 crore budget. I had become overconfident from all that we had managed to achieve, even on the VFX front, coming from Haider.”

◆ ◆ ◆

There is genuine integrity/sincerity that Vishal exudes during conversations, and in general too, as his former peers/associates always testify, when his name crops up.

At a recent concert in Mumbai with singer-wife Rekha Bhardwaj, their first time together—they met at Delhi’s Hindu College in the ’80s—she called him a “genius”. Which was one way to put it, as we watched Vishal go from soft ghazals to unexpectedly banging it with the vocals to Kaminey’s Dhan te nan on stage!

But along with the ‘shayrana’ mellow, there is also a hardcore side to his personality, I reckon. For instance, I point to him a tweet I came across long ago, where he made a political statement. A troll in the comments section taunted him, asking who did he thinks he was?

Normally, people ignore response, when none is merited. Scrolling down the screen, I noticed Vishal, 58, tell the troll: “Tera baap hoon [I’m your pop].”

He laughs, but declaims, in all seriousness: “There is a gangster in me. Maybe in retirement, the poet is taking over. But the spirit is there—against injustice, or if things aren’t going my way.” Consider this untold story of Maqbool (2004), his breakout film, that is on its 20th year.

One of the things I noticed about Maqbool, seeing it after long, is how little Bombay there is, in terms of live location, in a film about the Bombay underworld. Which can also be said for Mani Ratnam’s Nayakan (1987), upon re-watch.

Some of this is deliberate, Vishal says: “By 2002-03, the Bombay underworld scene had shifted to terrorism. We actually wanted to show a more old-world mafia with Maqbool.” He had knocked on every door to fund the film. Including the possible cast—for instance, Kamal Haasan was the original choice for the title role.

IDBI Bank had launched a scheme to finance films then. Vishal applied there as well. Producer Manmohan Shetty was on its script consultation committee. As was producer Bobby Bedi.

Manmohan had him over for a drink, simply to tell Vishal that he had saved his ass: “You have actors like Naseer, Om Puri, Pankaj Kapur… How would you’ve ever recovered a Rs 2.86 crore loan? I did you a favour, by rejecting it.”

Bobby, however, showed interest in the script, to come on board, with the funds. That’s how Maqbool kickstarted. How does one arrive at the old-world look?

Vishal says, “I had seen a haveli in Bhopal, which is exactly where we needed to shoot [Don Abbaji’s world]. So, 25 days in Bombay, 25 days in Bhopal. That was the shoot.

“Only, that once we got to the Bhopal leg, Bobby said there was no budget for it. And that there is a mansion at the Films’ Division office [on Pedder Road in Mumbai]—it’s colloquially called the ‘Films Division haveli’—where we could shoot. I said I won’t. He said he won’t make the film then. I said, let’s not make the movie!”

It was a Friday evening, Vishal remembers. He got home, made himself a few stiff drinks, and switched off his phone for the next two days. Bobby came knocking at his door on Monday, asking why he’d gone incommunicado?

“I told him, what’s the point of meeting? My fees for the film, including music composition, direction, script, was Rs 30 lakh. Bobby suggested that the Bhopal shoot would cost Rs 60 lakh. And that he was willing to put in R30 lakh, and I could put in my Rs 30 lakh.

“I just said—if you had told me earlier, I wouldn’t have drunk so much on Friday! Even to this day, while I was the producer, I didn’t make a single penny from Maqbool. But how does it matter? Look at all that I earned!”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!