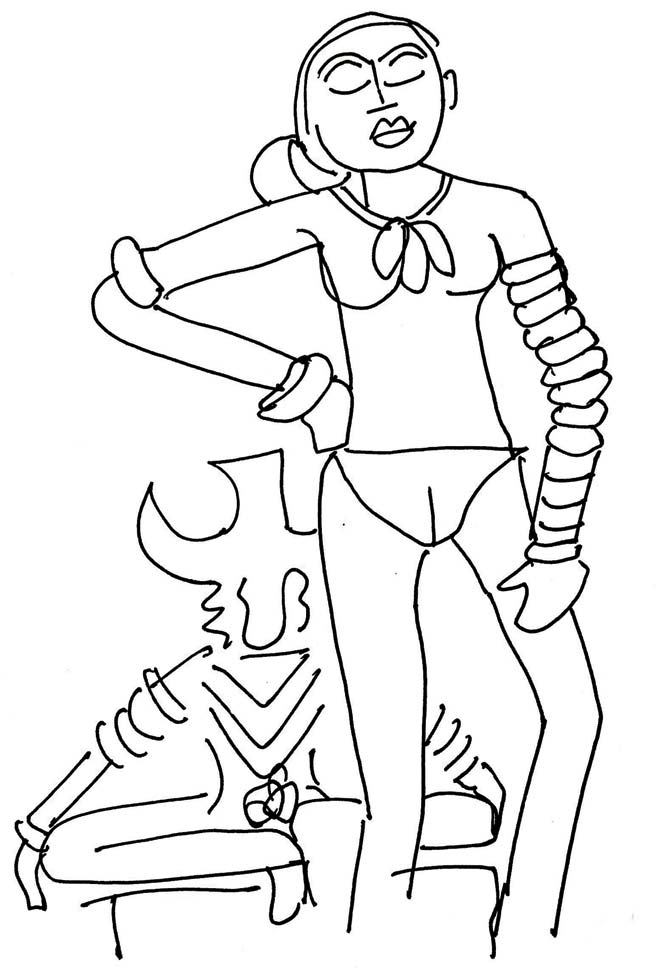

All my life I had seen photographs of a Harappan girl, found in the ruins of Mohenjo Daro, standing with attitude, face up, one arm on her waist, the other on her slightly bent knee

Illustration/Devdutt Pattanaik

ADVERTISEMENT

All my life I had seen photographs of a Harappan girl, found in the ruins of Mohenjo Daro, standing with attitude, face up, one arm on her waist, the other on her slightly bent knee. She is naked except for a string of bracelets that covers her left arm entirely, very much like Banjara women today. She has three cowrie-like pendants around her neck. British archaeologists called her a ‘dancing girl’ and the name stuck though there is nothing to suggest that she is dancing or trained in dance. Were they assuming she was similar to ‘nautch’ girls of Hindu temples and royal courts? She could very well be the bangle-seller’s daughter. Or a local princess. Or maybe an exasperated girl-child, because she did not like the food prepared. We really don’t know.

All my life I had seen photographs of a Harappan girl, found in the ruins of Mohenjo Daro, standing with attitude, face up, one arm on her waist, the other on her slightly bent knee. She is naked except for a string of bracelets that covers her left arm entirely, very much like Banjara women today. She has three cowrie-like pendants around her neck. British archaeologists called her a ‘dancing girl’ and the name stuck though there is nothing to suggest that she is dancing or trained in dance. Were they assuming she was similar to ‘nautch’ girls of Hindu temples and royal courts? She could very well be the bangle-seller’s daughter. Or a local princess. Or maybe an exasperated girl-child, because she did not like the food prepared. We really don’t know.

When I saw the actual statue for the first time, at the National Museum in New Delhi, I was quite disappointed that it was really tiny (11 cm approx). I remembered how, a few years ago, a politician had protested against the publication of the dancing girl image in a diary as his wife found the image vulgar. Recently, Pakistan staked its claim on her. And now, some scholars are seeking to refer to her as the Hindu goddess, Parvati, wife of Shiva.

Parvati means ‘mountain girl’. And her story comes to us from the earliest scriptures of the Puranic Age (Ramayana and Mahabharata). This Puranic Age dawns in the centuries after the rise of Buddhism (2,500 years ago), and counters the Buddhist doctrine of renunciation by reframing Vedic Hinduism explicitly as stories of householders. This happened roughly 2,000 years ago. The Harappan dancing girl is much older, maybe 5,000 years old. So, she could not have been Parvati.

Of course, this is information as per historians, who depend on archaeological and textual evidence. This often does not matter to religious leaders or politicians. Many believe that Harappan civilisation was Vedic and so Parvati’s tale may have been orally transmitted for centuries before being put down in writing in the Puranas. But the Vedas, that reached their final form about 3,000 years ago, do not refer to Parvati, or to Shiva.

But, there is always another argument to establish Harappan as Hindu. There are those who believe that Tantra comes to us from Harappan cities, and forms one of the two major tributaries of Hinduism, the other being the Vedas. And so, clay seals found in Harappan cities have images that suggest Tantrik practices. There is the image of what looks like proto-Shiva, and so, the dancing girl must be proto-Parvati. She may not have been called Parvati then, but story of a princess marrying a hermit and making him a householder may have emerged from here.

These are all speculations of course – both ‘dancing’ girl and Parvati. Many people believe that a ‘perfect and fully formed’ Hinduism existed in India before it was destroyed by Muslim and European rule. Here, Parvati always existed. However, those who value archaeological and textual evidence know that Hinduism has constantly transforming with inputs from various cultures, some indigenous, and some foreign, some imported, some co-created, a river with many tributaries and branches. Here, Parvati came centuries after the ‘dancing’ girl. Ultimately, we accept what comforts our ego or self-image. And transmit that to our children, sometimes via teachers and textbooks.

Devdutt Pattanaik writes and lectures on the relevance of mythology in modern times. Reach him at [email protected]

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!