Last week, on the 28th of June, people in various cities around the country came out to protest, under the title #NotInMyName

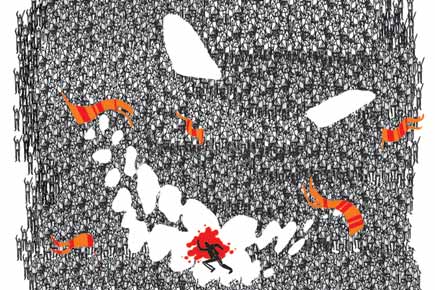

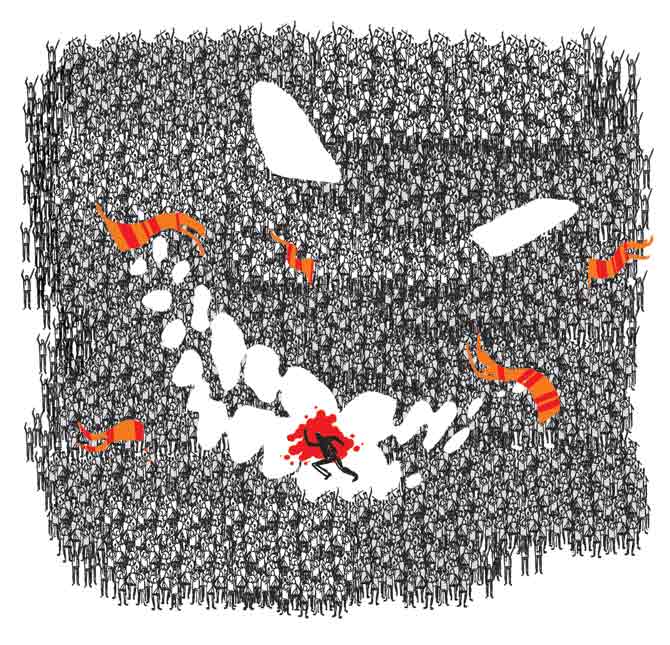

Illustration/ Ravi jadhav

ADVERTISEMENT

Last week, on the 28th of June, people in various cities around the country came out to protest, under the title #NotInMyName.

Last week, on the 28th of June, people in various cities around the country came out to protest, under the title #NotInMyName.

What were they protesting? On the surface, the shocking murder of 15-year-old Junaid in a suburban Delhi train, using the excuse of beef, propelled by not only hate, but the language of casual cruelty and avid callousness that is increasingly normalising violence around us.

For one of my young colleagues, this was her first time going to a such an event. She said, "It was amazing. But I kept thinking, 'OK, but now what? So what?'" In a sense she very simply articulated common critiques of such protests. What impact will this have? It is as if a political gesture must have a political revenue model.

Indeed, a protest is of course, sometimes just symbolic, like umbrellas in the Mumbai rain. But, maybe some things matter because their effect is absolutely

indiscernible and cannot be spun into a hashtag.

There are more complex critiques — the language of such protests is elitist, driven by upper caste and secular elite imaginations and concerns. Others point out that the phrase #NotInMyName is curiously moralistic, as if implying that violence and prejudice are okay in someone else's name and positioning oneself as somehow purer and so, superior.

These critiques have resonance, and are necessary, because some of the conversation about politics is also about the politics identity and of language — verbal and non-verbal, spoken and structural.

I, too, am among those who felt uncomfortable with much of the language of the protest. I have long felt critical of the model of self-less-ness where we establish ourselves as noble by speaking for others, as if we are not implicated in a political narrative, speaking of one thing, while silent about another, that other sometimes being our own privilege. Yet, I went. If I cannot stand next to people I disagree with and listen, or express my disagreement, what expectation can one have of a kinder, richer world?

Yet, at the protest I heard less of the old progressive certitudes. I don't even know if we should call these protests, as much as demonstrations. Many people there had never been to such a gathering before. Yes, they were not diverse — but that doesn't mean they won't ever be. Many had, perhaps for the first time, stepped out of the thrum of the online universe into a place of offline connections. I heard doubt, an open-ended need to simply demonstrate a set of beliefs — fairness, a government which treats all citizens the same, even kindness and love. Few certitudes, many questions.

The power of questions is often invoked and yet, so few people think of questions as politically meditative acts. Questions become weapons we bark at each other, hangers for dripping contempt.

But questions can become talismans and compasses, allowing us to search for new connections, new directions, new political languages.

We speak glibly of "a movement" but perhaps we need to remember it really is about movement — of shifting ideas and emotions, of turning questions and assumptions, Sometimes a so-called protest, may simply be a place — to find community, or affirm faith in one's beliefs, to find the courage to face hard questions, remember that a crowd does not have to be a mob — and take these back into the world, as it changes with you.

Paromita Vohra is an award-winning Mumbai-based filmmaker, writer and curator working with fiction and non-fiction. Reach her at www.parodevipictures.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!