Godavari Parulekar's book, residing in public memory for the last half century, recounts an agrarian revolt that instills faith in community action even today

Today's CPI (M) leadership in Talasari, standing at the iconic Warli revolt spot, believes that it was Godavari Parulekar who explained the meaning of Communism to the Warli tribe, awakening them to their rights

![]() Our regards to Lakshman Barkya and other Warli members of Rankol and Shelat. We are all fine. Tell Vithal Barkya that his crop has been cut properly. All of you all, don't worry about your farms. Also, we are taking care of your wives and children. We are hopeful and you too do not lose patience, even if you have to spend some more time in jail. Our Red Flag's lawyers are trying their best to defend you.

Our regards to Lakshman Barkya and other Warli members of Rankol and Shelat. We are all fine. Tell Vithal Barkya that his crop has been cut properly. All of you all, don't worry about your farms. Also, we are taking care of your wives and children. We are hopeful and you too do not lose patience, even if you have to spend some more time in jail. Our Red Flag's lawyers are trying their best to defend you.

ADVERTISEMENT

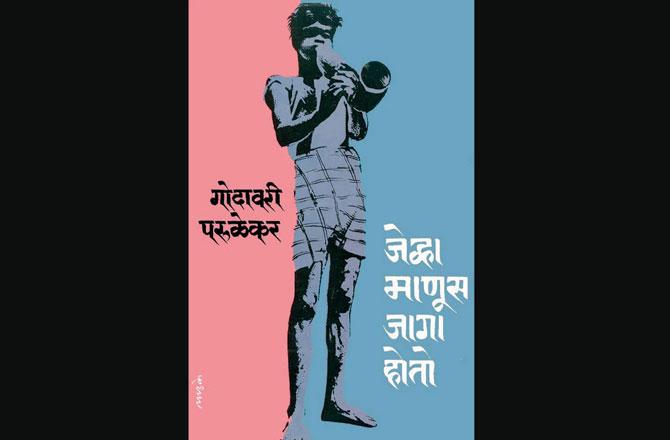

This is a collective letter, written by four Warlis—Maya Deviji Vayda, Lahangya Navshya Vartha, Harji Sutar and Rishya Shidba Labad—to their brethren who were jailed and isolated because of their participation in the peasant uprising against bonded labour, unfair wage practices, illegal land acquisition and social-sexual exploitation of Warli women. The letter is excerpted by late Communist leader-writer Godavari Parulekar in her defining 1970 Marathi book, Jevha Manus Jaga Hoto—Mouj publishing house will soon release its 18th edition—which won the Sahitya Akademi and several other awards and was translated into English, Japanese and regional Indian languages over the past five decades.

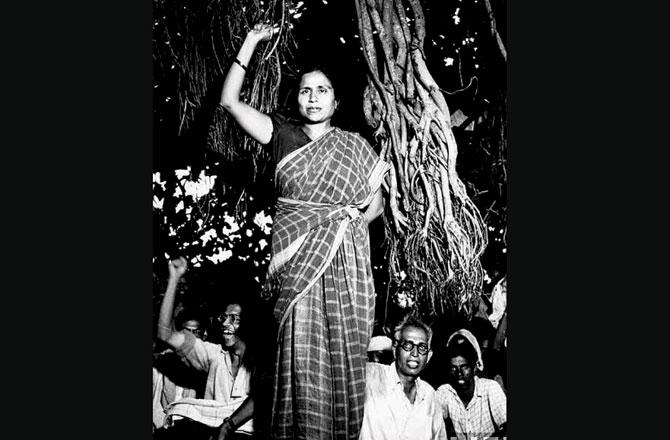

Parulekar, aka, Godutai started chronicling the revolt in the late 1960s, after the death of her husband, and fellow comrade-freedom fighter Shamrao Parulekar. Pic courtesy/Umesh Naresh Shingade

Comrade Godutai, as she was lovingly called, attaches tremendous cultural-social value to the letters of assurance written by fellow Warlis in the beginning of 1947—a time when the country was feverishly seeking freedom from the British, whereas indigenous communities like the Warlis were fighting for basic human dignity. As the author recalls with pride, the Warlis felt a deep sense of affinity for their homegrown warriors who dared the landholders, police patils, mukadams, talathis and magistrates who had jointly perpetrated cruelty on them for years.

Though uneducated, untrained and unexposed to the ways of the civilised world, the Warlis demonstrated exceptional mass mobilisation acumen in the revolt that ultimately led to the abolition of bonded labour practices, Godutai acknowledges. She says the Warlis not just followed orders religiously, but effectively assisted Communist leaders who were operating from underground. The Warli volunteers carried out secret missions and most importantly did not stop their agitation amid police firing. Warli women played an exemplary courageous role in holding the fort, while the men collided headlong with corrupt forest authorities, which didn't believe in the concept of fair remuneration to the adivasi worker.

Jevha Manus Jaga Hoto (Mouj publishing) won Godavari Parulekar the Sahitya Akademi award and several others. The text was translated into English, Japanese and regional Indian languages

Godutai started chronicling the 1940s revolt in the late '60s, after much persuasion, because she couldn't get over the loss of her husband-fellow comrade-freedom fighter Shamrao Parulekar, who had introduced her to the life in Dahau-Talasari-Umbargaon tribal belt. Born in an affluent Puneri Brahmin family, young Godavari Gokhale was raised in the varan-bhaat-toop comfort (she reminisces at various points in the book) provided by her renowned lawyer-father. Later, she became Maharashtra's first female law graduate. But, it was her activism (leading to imprisonment) against the British rule that took her to Mumbai. Her involvement in the Servants of India Society, her unionisation of domestic workers, brought her closer to her future husband. As they joined the Communist Party of India in 1939, joining the CPI(M) in 1964, they were against supporting Britain's World War effort. After 1942, both of them consciously dedicated their lives to the cause of farmers and adivasis. Therefore, Godutai's story is that of a spectacular crossover. It is an urban woman's earnest effort to lend herself to a remote rural milieu, backdropped against the Indian freedom movement. In the words of Pune-based publisher, and former CPI member, Arvind Patkar, the book is a reference bible for any grassroots worker, Communist or otherwise. "She literally walked miles in the tribal hamlets in Dahanu and Talasari when tar roads were unheard of. She lived with the Warlis when electricity and tap water were a rich man's privilege. As young comrades, we were guided by her example."

Parulekar's account of the Warli agitation is honest to the core. She shares her self-doubts, fears, insecurities with the reader. After walking on the muddy uneven hilly terrain in Talasari, she yearns for a cup of hot milky tea. Coarse uncovered bhakris and a tangy aambil, served at unearthly hours, put her off instantly. She is unable to locate a decent washroom for days. Her desperation for urban conveniences is conveyed without filters. There is an entire chapter devoted to the 'shelters' she called home while unifying the Warlis against a corrupt nexus. The landowning class, against whom she spoke, ensured she wasn't given an accommodation in Dahanu or around. She spent a night under a tree, not to forget the horse stable and a Ganesh temple she temporarily inhabited. "Her struggle is relevant till date because it underlines the adjustments that a grassroots worker should be mentally prepared for," says comrade Ashok Dhawale, the national president of All India Kisan Sabha, a position once held by Godutai.

As senior-junior Communist volunteers affirm, Godutai was steadfast in her belief in Communism (as a philosophy), irrespective of global developments or national-level setbacks to the Left in the 1990s. It was this courage of conviction that empowered her in the Warli revolt. In plain simple terms, she explained the meaning of Communism to an unlettered Warli. Needless to add, her tutorial gave them lasting strength to fight for their cause, even when Godutai was arrested and later barred from entry in Thane district. As old-time comrade Laxman Bapu Dhangar, 92, says, the book reminds us of a courageous leader who sensitised the Warlis to their basic rights in a free country.

Writer Heramb Kulkarni, who recently commemorated the 50th year of Godutai's book by hosting a symposium of varied voices (like Narmada Bachao leader Medha Patkar and social worker Prakash Amte), feels the succeeding generations are grateful for her painstaking record of the social-political order in a tribal region that is mere three hours away from the financial capital.

While Jevha Manus Jagaa Hoto is undoubtedly inspiring, there is one aspect of the book that puzzles me. The Marathi in which Godutai expresses herself is distinctly archaic and often acutely Puneri. Those who knew her well vouch for her warm, pro-people, inclusive and conversational idiom. Many insiders say the "purple prose" she mouths in the book is that of the editor. For instance, Dr Dhawale, along with spouse Mariam—general secretary of CPI (M)-aligned women's association—interacted over a range of issues with her, till her final years at her Sham Savli Juhu bungalow. "She was a natural, in all dimensions, language-wise too," comrade Dhawale adds. Unfortunately, there is no one (with vintage years) in the publishing house who can throw light on the chosen narrative style of the book.

As we leaf through Godutai's story, current-day Dahanu and Talasari, now motorable tourist destinations, come to our consciousness. Wellness resorts dot the Dahanu-Ahmedabad stretch. Warli schoolgoers use smartphones to tune into Chala Hawa Yeu Dya. Warlis and other indigenous tribes in the region are represented in state government bodies. The current MLA from Dahanu, Vinod Nikole is a Warli. There is perceivable development, so to say, if one were to recall the social situation depicted by Godutai. Of course, she believed in several indices of holistic development—including equitable use of natural resources and preservation of native language-heritage—which still need to be achieved.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at [email protected]

Keep scrolling to read more news

Catch up on all the latest Mumbai news, crime news, current affairs, and a complete guide from food to things to do and events across Mumbai. Also download the new mid-day Android and iOS apps to get latest updates.

Mid-Day is now on Telegram. Click here to join our channel (@middayinfomedialtd) and stay updated with the latest news

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!