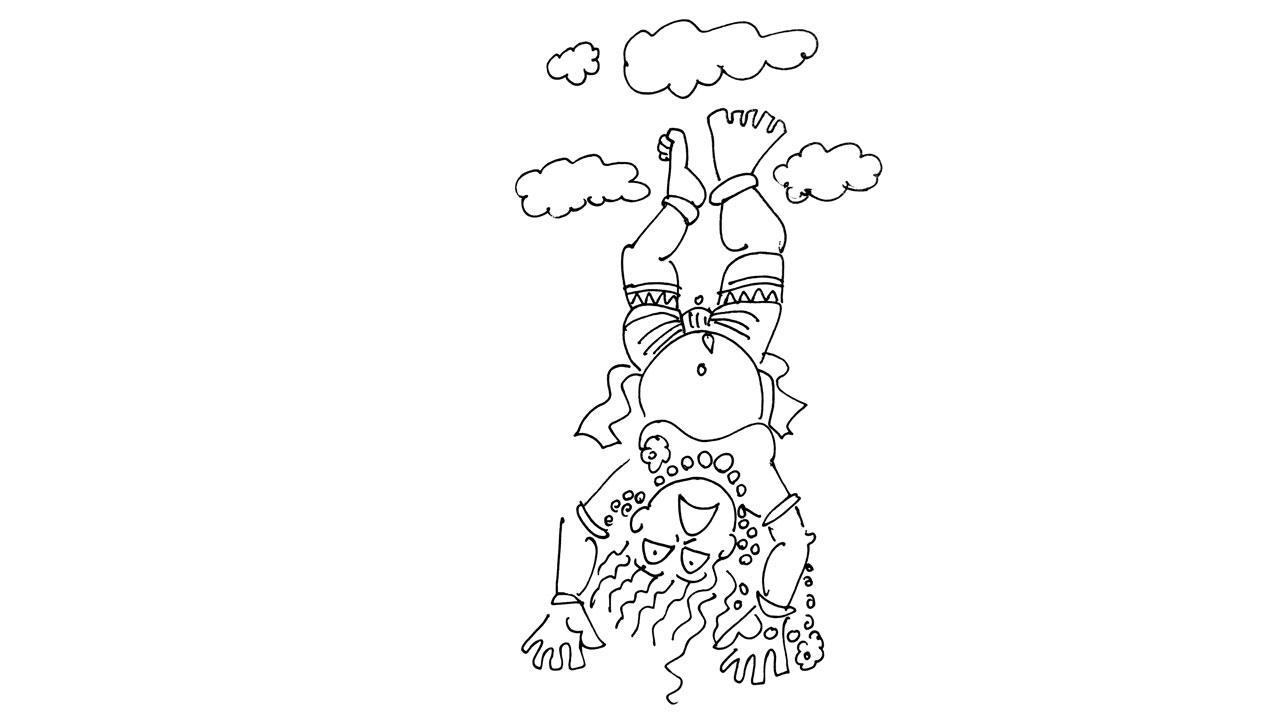

Trishanku fell downwards but Vishwamitra blocked his fall, suspending him mid-air.

Illustration/Devdutt Pattanaik

Once upon a time, there was a king called Trishanku who wanted access to Swarga, the paradise of the gods, located in the sky. But unfortunately, he was not good enough. Different versions give us different reasons: that he had committed adultery, that he had consumed beef, that he had broken caste rules. The point is Indra, king of the gods, would not let him enter Swarga. He was not dharmic enough.

Once upon a time, there was a king called Trishanku who wanted access to Swarga, the paradise of the gods, located in the sky. But unfortunately, he was not good enough. Different versions give us different reasons: that he had committed adultery, that he had consumed beef, that he had broken caste rules. The point is Indra, king of the gods, would not let him enter Swarga. He was not dharmic enough.

ADVERTISEMENT

So, the king sought the help of Vishwamitra, a rebel seer, who had defied the odds and made himself a Rishi. Born a king, Kaushika had chosen the mystical, occult, spiritual path, and made himself a Rishi, one with powers to even defy and control the gods. He promised to get Trishanku to heaven. Trishanku rose from the earth, and made his way through the atmosphere, towards the sky. But Indra refused to let him enter his abode. “Go back to earth,” he said.

Trishanku fell downwards but Vishwamitra blocked his fall, suspending him mid-air. There he remained, neither up nor down, neither up in the sky nor down on earth. Some say he is the Southern Cross constellation that appears in the Northern Hemisphere in summers. Others say he is the coconut, head upside down.

Trishanku is a metaphor for those who belong neither in the realm of the gods nor in the realm of humans. The middle class. Those who have power but still feel powerless. The oppressor who feels oppressed. The in-between liminal people.

Significantly, in Hinduism, gods appear in liminal spaces. Like Narasimha—the form of Vishnu who is neither animal nor human, who protects his devotee Prahalad from his demon-father, who cannot be killed at day or night, by killing him at twilight. The demon-father cannot be killed inside or outside a dwelling so Narasimha kills him at twilight. The demon-father cannot be killed on the ceiling or on the floor and so he is killed suspended on Narasimha’s thigh.

The Trishanku story tells you about feeling disempowered by belonging neither here nor there. Narasimha story tells you about feeling empowered by being in between, here and there. Queer people are the in-between people. Neither here nor there. Both here and there. They can choose to feel disempowered like Trishanku or empowered like Narasimha.

But some people like to belong to one extreme—either the eternally oppressed activist or the eternally oppressing politician. Those who are forever victims or forever villains. Those victims who use their victimhood to dominate the conversation. Those villains who use their power and privilege to be eternal snobs. Those who cannot empathise with the other. Those who cannot know how we all move up and down, between worlds.

In politics, we see how leaders seek to be in Indra’s heaven. But are pushed out. They do not fall on earth but remain suspended in between. Neither god nor human. Having lost favour of both. They are higher than everyone else but not as high as they wish to be. So, they feel like a fallen being. Not low enough to be humble though. Grumbling at how unfair the world is to not let them be the god they wish to be.

The author writes and lectures on the relevance of mythology in modern times. Reach him at [email protected]

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!