The play Madhurav: Boru Te Blog charts the birth and evolution of the Marathi language, honouring the lesser-known individuals whose work enabled its dynamic, contemporary avatar

Akansha Gade and Madhura Welankar-Satam have each other’s backs, as they present Marathi’s evolution on stage

![]() It was on January 6, 1832 that a 20-year-old Bal Shastri Jambhekar founded the Marathi newspaper Darpan. Every year, this day is celebrated as Marathi Patrakar Din—to remember Jambhekar’s journalism, which took on the British.

It was on January 6, 1832 that a 20-year-old Bal Shastri Jambhekar founded the Marathi newspaper Darpan. Every year, this day is celebrated as Marathi Patrakar Din—to remember Jambhekar’s journalism, which took on the British.

ADVERTISEMENT

This commemorative day generates predictable copy on Jambhekar’s belief in the printed word. But the social reformer had many other dimensions. He was a celebrated polyglot with a hold over eight-odd languages; he set up the Bombay Native General Public Library—one of the foremost institutions which shaped 19th-century Mumbai. He was a person of eclectic literary and scientific pursuits which reflect in his varied achievements. Not only was he the director of the Colaba Observatory, but he was also the author of the Encyclopaedic History of English Grammar.

Jambhekar’s greatness is the stuff of books which engage lovers of Mumbai’s history. But I was pleasantly surprised to meet him as one of the lead characters in a two-hour Marathi play penned by Dr Samira Gujar-Joshi. Madhurav: Boru Te Blog is a melodic musical recounting of the key personalities (and institutions) who nourished the Marathi language, beginning with the Satavahana dynasty (particularly Hala Raja, 20-24 CE, whose 700 gathas added to the language’s depth) which recognised Maharashtri Prakrut, a linguistic predecessor, as the administrative tongue.

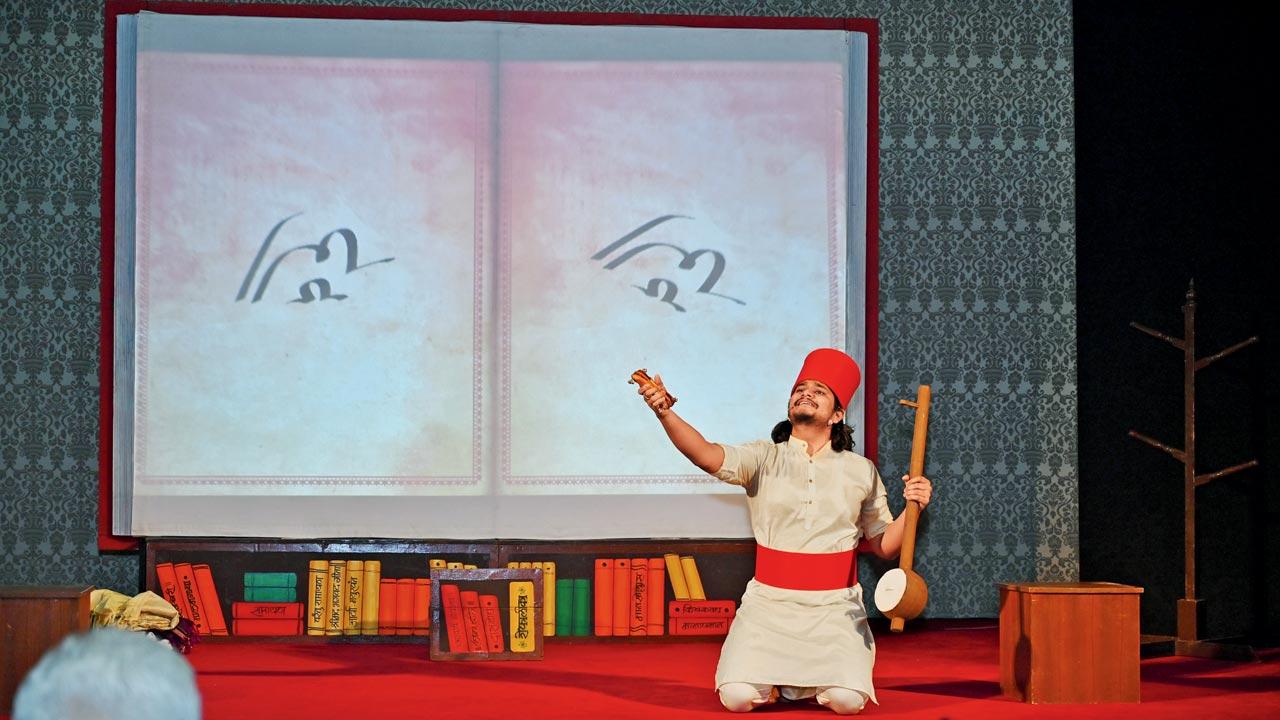

Ashish Gade depicts Muslim saint-poet Shekh Mahammad baba’s teachings on the healthy confluence of language and culture

Ashish Gade depicts Muslim saint-poet Shekh Mahammad baba’s teachings on the healthy confluence of language and culture

Three actors—Madhura Welankar-Satam (also the play’s director-producer), Akansha Gade and Ashish Gade—take a chronological, choreographed journey through the ancient, medieval and contemporary stages of Marathi’s usage for the present-day speaker. In an interactive Q&A-style narration, interspersed with a rich audio track, Welankar-Satam leads the discourse by answering queries from the younger actors about Marathi’s power of articulation, adaptability over 2000 years, openness to absorbing newer influences, varied sources of royal patronage, mass appeal, and most importantly, the resilience to encompass new spheres of experience.

Madhurav: Boru Te Blog is cute and alliterative, but also misleading, supposedly conveying the transition from the ancient bamboo stylus (boru) to the modern computer keyboard, which helps common people to blog about everyday life. It treats the average theatregoer to a dose of linguistic history, peppered with necessary song-and-dance components, a tinge of humour, a dash of melodrama (a soliloquy delivered by Samarth Ramdas’ ‘wife’ is stretched for emotional effect), loads of feel-good “lets speak Marathi” resolution moments—all against the backdrop of an enlarged screen which shows the faces and institutions which have shaped the language over the years! While some individuals are easily identifiable, others are lesser known. Consider shahir Vamandada Kardak who infused the Girgaum textile mill working class ethos into literary Marathi; or courtier poet BR Tambe who immortalised poetry in the language during his time as a royal teacher in Dewas. Tambe studied in Allahabad and lived mostly in the Gwalior princely state, but his poetry created a sensation in Maharashtra. His most popular song, Jan palbhar mhanatil haay haay, has been immortalised by Lata didi.

With minimal props and a lean team of performers, Madhurav is a noteworthy attempt in the right direction. Most importantly, it is not aggressive in its delivery and appeal for a wider usage of Marathi. It does not strike a jarring note of hatred for the ‘other’ languages or cultures. Neither does it claim to be an all-inclusive authority on all-things Marathi. It brings to life enlightened souls like Jambhekar, who enriched the language by lending themselves to other Indian and foreign tongues. Jambhekar was the first native Indian professor of Hindi at Elphinstone College, and among his pupils were Dadabhai Naoroji and Bhau Daji Lad. Of course, playwright Gujar-Joshi could have at least mentioned some non-Maharashtrians who have served the cause of the language, such as British lexicographer James Molesworth and Jesuit missionary Thomas Stephens.

“Every show encourages the audience members to suggest new nuggets about forgotten writer-litterateurs or other lesser acknowledged aspects of Marathi’s uniqueness. We are even open to distilling the content into new thematic focus areas, like saint literature, the language of the culinary world, travelogues, and Marathi letter writing tradition,” says Welankar-Satam, an award-winning actor known to be a natural, whose work spans theatre, cinema, TV, and ads. A book on her musings during the pandemic is a bestseller, and she was instrumental in uplifting amateur writers through her online writing project. Welankar-Satam was recognised as a COVID-19 warrior for building a vibrant online community of novice writers and social media influencers at a time of social isolation. In fact, she conducts a quick pop quiz in every live performance of the play; her goodie bag for the winner adds to the audience’s excitement.

Madhurav is replete with aha moments of discovery and insight for two varieties of language lovers—the uninitiated-but-interested, as well the deeply invested. As the narrative is linear, it begins with the beginning: the pre-writing, pre-printing stage of the spoken idiom which matures into the evocative powerhouse that it is now, albeit the 15th most spoken in the world and unrecognised as classical. The trajectory includes stone inscriptions in Marathi dating back to 1 century BCE. The language survived due to its firm hold in popular memory, even before it was recorded in a written script.

Just as the language was promoted by dynasties in power (the Yadavas included) who wished to woo Marathi-speaking subjects, it also grew because of religious sects. Mahanubhav Panth’s Chakradhar Swami propagated his doctrine in Marathi, denouncing a ritual-ridden, dogmatic religion in the language of the commoners. To date, Chakradhar Swami’s biography Leelacharitra is one of the first known Marathi treatises. Saint Dnyaneshwar (1275-96) chose Marathi as the medium for his Dyaneshwari (commentary and more on the Bhagavad Gita) and Amrutanubhav—two milestones which have forever characterised Marathi literature.

Madhurav rightly honours all the poet-philosophers of the Warkari sect, who popularised Marathi ovis and abhangs to speak of equality of all humans before the Almighty. Sweet and empathetic are these saints’ thoughts—be it Tukaram’s “dev aahe antaryami, vyarth hinde teerthgrami” (God is within; you needlessly seek him in pilgrim precincts) or Janabai’s “Jyacha sakha Hari, tyavari vishwa krupa kari” (The one who befriends the Lord, is blessed by the world).

There is one serious lack, however, that the play should address in its future editions: It doesn’t currently factor in the contribution of dialects in the enrichment of the language. Just as the Marathi used in the corridors of Mantralaya or the purple prose in Diwali Anks have their own significance, dying dialects such as Malvani, Varhadi and Ahirani are lifelines for communication. Even tribal languages like Warli, Korku, Thakar, and Bhilori need to be accorded their rightful place. They bring their own colour, vitality and madhurav (melodic music) to the mainstream. Their death is our collective and irreparable loss.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at [email protected]

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!