Two centennial commemorative volumes, co-edited by Kolhapur’s Chandrakant Langare, bring 41 global scholars under one roof to unravel Joseph Conrad’s literary genius

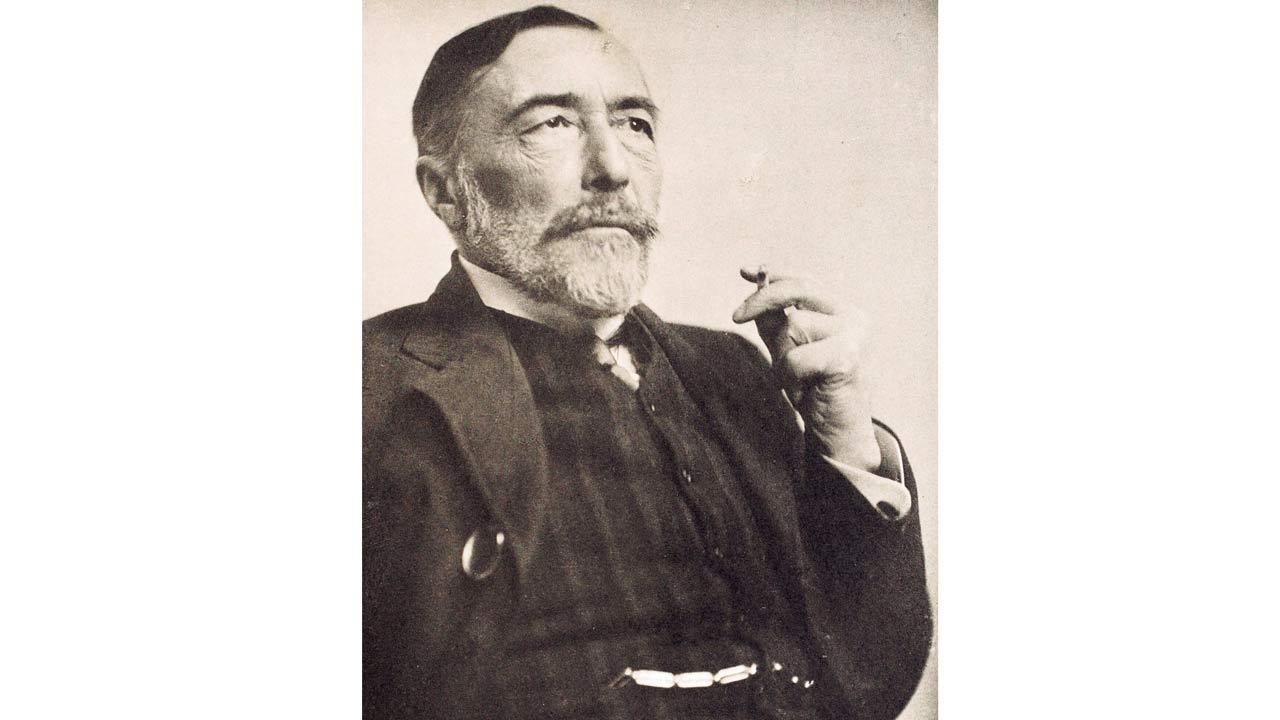

Polish-British novelist Joseph Conrad

![]() Polish roots, French influences, a British identity, and extensive global travels—including a brief stay in India—are a great recipe for being remembered and reinterpreted in diverse cultural contexts even a hundred years after one’s death. Joseph Conrad, the Polish-British novelist, is best known for his iconic works like Heart of Darkness, Lord Jim, Nostromo, and The Secret Agent— stories that delve into morality and human frailty, relevant even in the contemporary conflict-ridden world.

Polish roots, French influences, a British identity, and extensive global travels—including a brief stay in India—are a great recipe for being remembered and reinterpreted in diverse cultural contexts even a hundred years after one’s death. Joseph Conrad, the Polish-British novelist, is best known for his iconic works like Heart of Darkness, Lord Jim, Nostromo, and The Secret Agent— stories that delve into morality and human frailty, relevant even in the contemporary conflict-ridden world.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Centennial Commemorative Book Project celebrates Conrad’s legacy with 41 global contributors, reexamining his works in light of contemporary global dynamics. Two upcoming volumes, The Centennial Perspectives and The Centennial Appraisal (Rawat Publications), are co-edited by John G Peters, Distinguished Professor at the University of North Texas, and Chandrakant A Langare, Associate Professor at Shivaji University, Kolhapur. Langare, whose doctoral research focused on Conrad, has coedited a book on his works and written extensively on Conrad’s life narratives. Peters, former president of the Joseph Conrad Society of America, offers his vast scholarship, including The Cambridge Introduction to Joseph Conrad.

Jeremy Hawthorn, Professor Emeritus at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, opens the volumes with Still Going Strong: Conrad’s Fiction a Hundred Years On, highlighting Conrad’s magnetic pull.

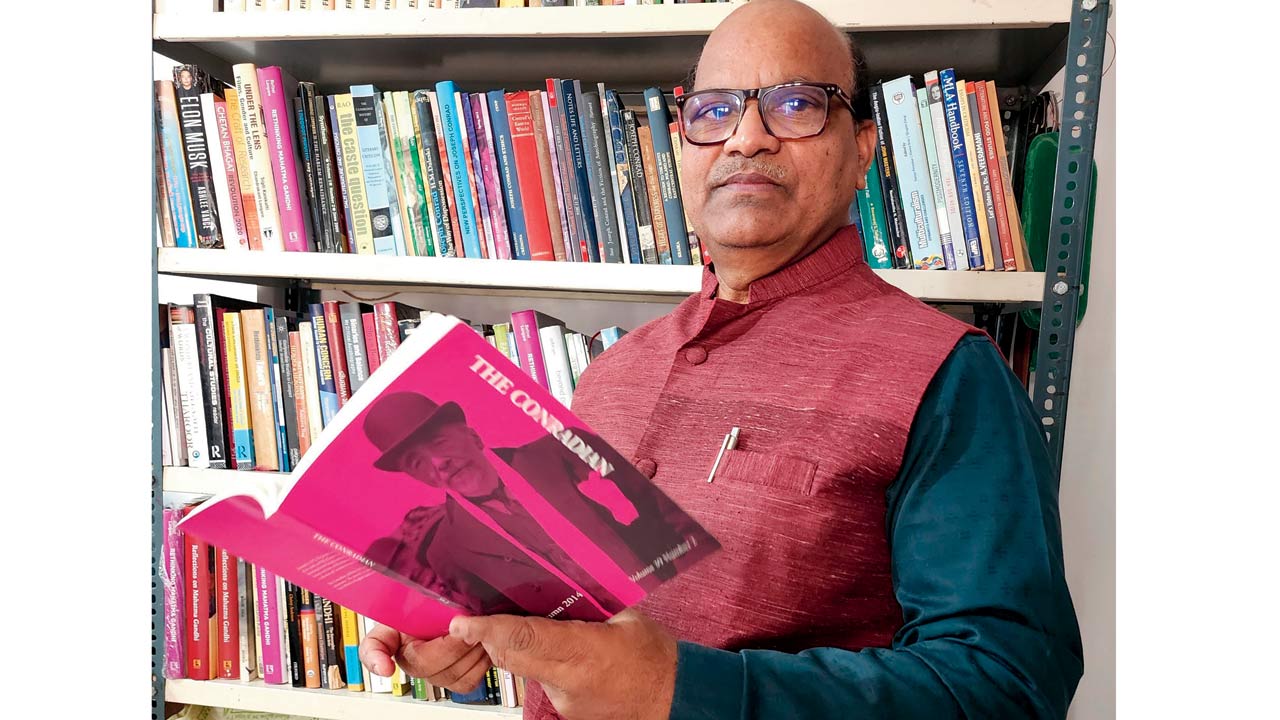

Chandrakant A Langare, Associate Professor at Shivaji University, Kolhapur, whose doctoral research focused on Conrad, has coedited two new books on his works and written extensively on Conrad’s life narratives

Chandrakant A Langare, Associate Professor at Shivaji University, Kolhapur, whose doctoral research focused on Conrad, has coedited two new books on his works and written extensively on Conrad’s life narratives

Conrad scholars span the globe, with Conrad societies in Britain, America, Poland, and Japan. While India lacks a formal society, Conrad’s work remains integral to English literature programs across the country. Seven Indian contributors to these volumes offer fresh perspectives on Conrad’s transnational and multicultural writing, focusing on identity in ways that resonate deeply within both Indian and colonial contexts.

Conrad is different to different Indian writers. Rajendra Chenni, a distinguished Kannada critic and Professor at Kuvempu University, Shimoga, compares Conrad with Rabindranath Tagore. Both responded to their eras’ intellectual challenges, offering a layered exploration of nationalism and its historical forces. Chenni contrasts their critiques of imperialism and nationalism: Conrad’s Heart of Darkness exposes the barbarity and absurdity of imperialism from a European viewpoint, while Tagore, in Four Chapters, critiques the manipulative, dehumanizing force of militant nationalism. Both authors highlight the dangers of ideology, making their works strikingly relevant.

Like Chenni, Subhadeep Ray, a postcolonial literature researcher, and Subhasnata Mohanta, a scholar of revolutionary narratives, examine The Rover by Conrad and Satinath Bhaduri’s Jâgari, highlighting their shared themes of revolution and resistance. Both stories interrogate politics, ideals, and the human condition. In The Rover, Conrad’s Peyrol, a former privateer seeking peace after violence, is drawn into an espionage plot in post-revolutionary France.

K Sripad Bhat, a narrative theory scholar, and Fayaz Sultan, a modernist literature expert, focus on Conrad’s mastery of multiple narrators and nonlinear storytelling in Nostromo. Editor Langare, who has presented on Conrad at international forums like the University of Kent and Roma Tre University, offers fresh insights into Almayer’s Folly (1895), emphasising how colonial greed leads to moral decay.

Nidesh Lawtoo, a professor of Modern and Contemporary European Literature at Leiden University, reinterprets Conrad’s work through the Anthropocene lens in his essay Conrad in the Anthropocene. He explores how Conrad’s depictions of typhoons and sea storms mirror the human condition in the face of catastrophe. Lawtoo, also the Principal Investigator of the ERC-funded Homo Mimeticus project, has written influential works, including Conrad’s Shadow: Catastrophe, Mimesis, and Theory.

Many Indian writers have explored Conrad’s use of the sea as a central motif. In The Sea, Sky and Everything: Buoyant – An Ideological Study of Heart of Darkness, M Shanthi and Deepa Prajith argue that the ocean symbolises more than a geographical boundary; it becomes a space of tension where the fluidity of nature reflects the instability of human morality. This forces characters like Marlow and Kurtz into darkness, both in the African wilderness and within their own psyches, underscoring the sea’s role in the narrative of self-discovery.

Not just Indian but other contributors also see the sea-connect. Tanaka Kazuya, a Japanese scholar, argues that The Shadow-Line reflects on crisis and resilience, with the ship symbolising society’s hierarchy and collective survival, drawing parallels to the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, James Mellor, in Hamburg, sees Conrad’s sea as a metaphorical space where life, art, and philosophy intersect, linking Conrad’s roles as mariner and writer, making it a space between experience and abstraction.

It is interesting that while many writers see a sea of possibilities in Conrad’s work, he sought to distance himself from being narrowly defined by maritime themes. As a former mariner in the British merchant navy, his seafaring experiences shaped his literary output. Early on, he was often compared to Rudyard Kipling as a colonial writer, with novels like An Outcast of the Islands depicting European colonisers and local populations. Later works, such as Typhoon and The Nigger of the Narcissus (a controversial title then and now), further cemented his sea-story reputation.

Robert Hampson, Professor Emeritus at Royal Holloway, University of London, notes that Conrad yearned to be freed from “that infernal tail of ships” and the reviewers’ obsession with his sea-life, which, he felt, obscured the full breadth of his literary vision.

Conrad’s sentiment resonates with Indian scholars and academics who resist being pigeonholed as Dalit writers or Muslim writers or regional litterateurs. Similarly, many Indian authors reject labels like “women writers” or “women’s writing”, as these limiting terms fail to encompass the broader human experience.

To remain relevant a century after his death is no small feat. Conrad’s works, shaped by European influences, reached global audiences, from the Soviet bloc to South America. He personally oversaw the publication of his works in English, Polish, and French, ensuring quality and broad accessibility.

Italo Calvino, one of Italy’s most celebrated postwar writers, praised Conrad for his sharp critique of colonialism, noting its resonance with young communists in post-war Italy. In stark contrast, Ted Kaczynski, the infamous Unabomber, cited Conrad’s The Secret Agent to justify his anti-technology bombing campaign. These divergent readings underscore Conrad’s ability to speak across ideological divides, revealing the trans-national scope of his work long before the concept of a global village took root.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at [email protected]

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!