Recalling the words of the Father of the Constitution makes most sense on the day when citizens exercise their most potent political right

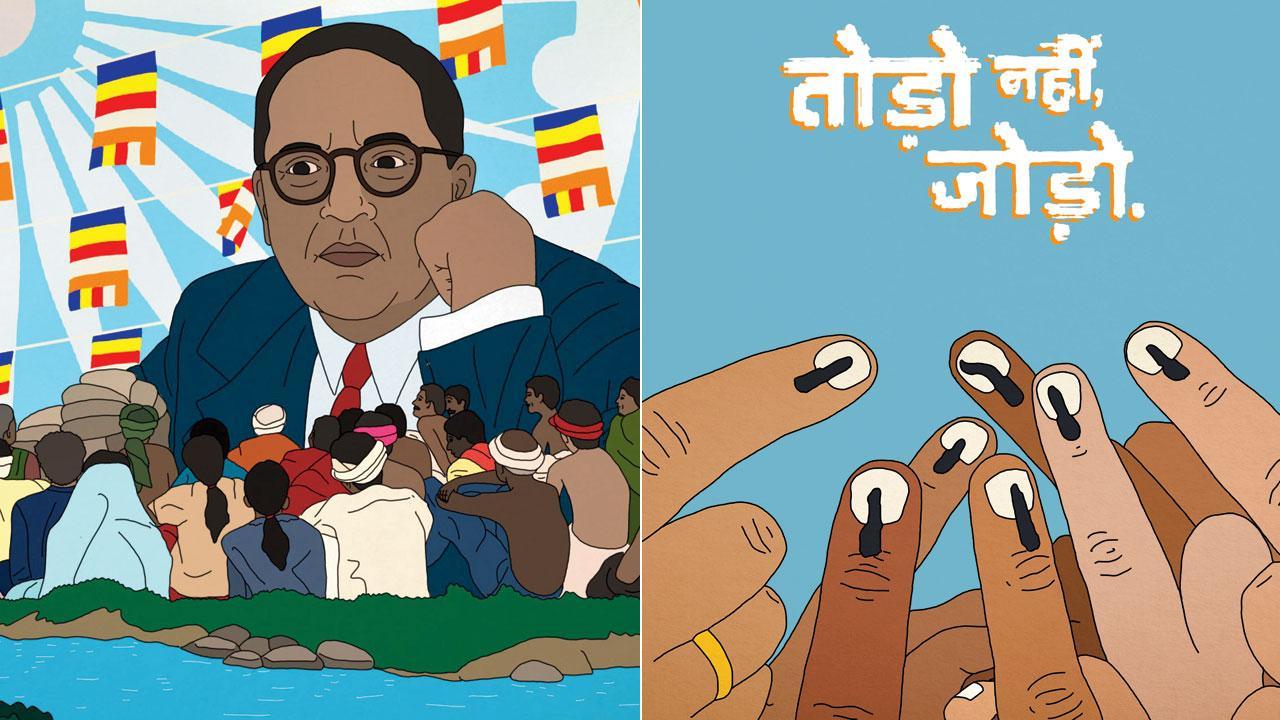

On Instagram, Noida-based multidisciplinary artist and proud Ambedkarite Siddesh Gautam’s illustrations reflect Dalit pride in blue. His handle @bakeryprasad has a deep-in-thought Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar in all avatars. His surreal and satirical work demands a caste-free world order. Illustrations/Siddhesh Gautam

![]() Democracy, in this country, is like a summer sapling whose roots cannot be strengthened without social unity; if social unity is not achieved, the sapling will be rooted out with a gust of summer wind, said the Father of the Indian Constitution.” The quote, one of the most excerpted, is part of 17 volumes of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches made freely available online by the government of Maharashtra.

Democracy, in this country, is like a summer sapling whose roots cannot be strengthened without social unity; if social unity is not achieved, the sapling will be rooted out with a gust of summer wind, said the Father of the Indian Constitution.” The quote, one of the most excerpted, is part of 17 volumes of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches made freely available online by the government of Maharashtra.

ADVERTISEMENT

On a scorching Monday in India’s hottest month when Mumbaikars brave above 39 degree celcius to exercise their suffrage and participate in the “festival of democracy”, Babasaheb’s “summer sapling” analogy sounds more relatable than ever. Mumbai will go to polls in the last leg of the six-week long seven-phased Lok Sabha elections. Since the day follows a weekend, the Election Commission and the state government are trying their best to tell people to treat the day with seriousness. Private as well as government firms are giving two-hour breaks for fulfillment of democratic duty. The My First Vote campaign prods the youth to vote, which is crucial in the second-most populous state, home to 90.03 million voters. More than ever before, Babasaheb’s definition of democracy and his idea of India becomes quotable.

His words radiated with hope as he saw his idea of an egalitarian democracy gaining mass. In an April 14, 1929 speech, he had said:

“India is likely to attain full control of its destinies in the coming four or five years. At that time you must take particular care to send to the Legislatures the right type of men as your representatives who would devoutly struggle for the abolition of this Khoti system.” He was addressing the Ratnagiri District Agriculturists Conference in Chiplun. He referred to his beginnings in the Improvement Trust Chawl and called the Khoti system (revenue collected by khots or landlords who exploited tenants and worked as agents of the British) as blood-sucking. Ambedkar introduced a bill against the system in the Legislative Assembly in 1947 which led to a series of protests in Ratnagiri. Even before India attained Independence, the fight against all inequities was mapped clearly on his priority list. As Mumbai chawls slowly become part of the redevelopment clusters in contemporary times, Babasaheb’s remarks on unfairness of a system stand out.

From the start of his political life, he urged the Depressed Classes to devote their energies to gaining political power. A moving speech he gave on September 28, 1932 at the open grounds of Worli’s BDD Chawls honestly explained his politics. While he owned up to the movement he launched in Nasik for the general public entry (including Dalits) in the Kalaram Mandir, he clarified: “The object of the temple entry movement is good. But you should care more for your material good, than for spiritual food.” Babasaheb openly condemned the caste hierarchy in the folds of the Hindu faith.

In a direct reference to Pandharpur Warkaris, he had once said, “The appearance of tulsi leaves around your neck will not relieve you from the clutches of the money lenders. Because you sing songs of Rama, you will not get a concession in rent from the landlords.” He said Indian society is absorbed in the “worthless mysteries of life, superstitions and mysticism, the intelligent and self-centred people get ample scope and opportunities to carry out their anti-social designs.” He appealed to people “to act and utilise what little political power is coming into your hands. If you are indifferent and do not try to use it properly, your worries will have no end.”

For him, democracy could not be achieved unless all sections were conferred equal rights. At the 36th anniversary of the Sant Samaj Sangh, a spiritual association of the Depressed Classes, in Poona in 1930, he emphasised that he would do his best to tell the British about the former’s grievances and secure as many rights for them as possible. He wasn’t satisfied with the Indian National Congress Party’s efforts to bring in equality. He resigned from the Nehru cabinet in 1951 (he was the first Law Minister, despite open differences with the PM) after the defeat of the Hindu Code Bill. He later contested for the Bombay North seat in India’s first General Elections in 1952 under the aegis of the Independent Labour Party, but lost to the Congress candidate. Babasaheb tried his luck in the 1954 by-election thereafter, but faced defeat in the Bhandara constituency. He had passed away when the country voted in the second Lok Sabha elections in 1956.

True equality was always on his mind, which showed in his speeches too. At the All-India Depressed Classes Congress at Kamptee (near Nagpur) in 1932, he said, “Untouchability in India will not be eradicated so long as the Untouchables do not control the political strings.” He believed that unless Hindu society reorganised itself on modern lines, and shattered the caste structure and “places country above creed”, India cannot succeed as a democratic nation. At one point he questioned Mahatma Gandhi too: “What is the effort made by Mahatma Gandhi to remove untouchability? Great as has been his moral support, he has contrived to translate very little of it into practice...” In fact, Ambedkar felt that unless Gandhi “quit the stage, it was absolutely hopeless to make any move to lift Indian politics from the present quagmire”. He had said this at the May 9, 1943 mass meeting of Scheduled Classes in Naigaum, Mumbai.

His clarity of vision reflects throughout his later speeches, particularly resonating are his final remarks on November 25, 1949 in the Constituent Assembly while presenting the Constitution. He asked Indians to strive for a social democracy instead of a mere political democracy with underlying principles of equality, liberty and fraternity. Also Ambedkar’s views on what it takes to be a true nation were conveyed too candidly, even by today’s tell-it-like-it-is standards. He maintained that a diverse India would “not automatically become a nation.” He said that “in believing that we are a nation, we are cherishing a great delusion. How can people divided into several thousands of castes be a nation?” But the sooner we realise that we are not, as yet, a nation in the social and psychological sense of the word, the better for us. For then only we shall realise the necessity of becoming a nation and seriously think of ways and means of realising the goal.” None of Ambedkar’s contemporaries have been so outspoken about the ill-effects of India’s caste system. “The realisation of this goal is going to be very difficult—far more difficult than it has been in the United States. The United States has no caste problem. In India there are castes…” He termed caste as essentially anti-national and a separatist force. He saw fraternity as a deep uniting coat of paint, which is annihilated by caste.

Ambedkar’s warning about the possible failure of democracy was also forthright. He said an independent India cannot blame the British or anyone if it fails. He said that to elect a responsible government that was made up of the people’s representatives was a duty henceforth. “Let us resolve not to be tardy in the recognition of the evils that lie across our path and which induce people to prefer Government for the people to Government by the people, nor to be weak in our initiative to remove them.”

For Babasaheb, public accountability was a value, especially in the case of public funds. His speech at All India Sai Devotees Convention (January 1954) on the St Xavier’s ground in Dhobi Talao, couldn’t have been more succinct. “We have not only gone the wrong way in the matter of religion but it has become a profession to collect money in the name of religion and waste it for purposes for which there can be no social justification. There is so much poverty and misery in the world that it is criminal to collect money in the name of religion and waste it on feeding Brahmins and other pilgrims.” He did not mince his words while expressing his aversion for the political power wielded by religious trusts across the board.

As the country readies to elect its 17th Lok Sabha (and Mumbai votes for its six parliamentary seats), the Moral Code of Conduct is in place to guide political parties and candidates about norms of processions, election manifestos, polling, speeches, meetings etc. At the core of the code lies the profound principle of accountability to the public, which the Father of the Constitution cherished for a lifetime. Voting day is a pivotal moment to heed his enduring faith and strive to honour it anew.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at [email protected]

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!