People were busy posting about “nature coming back”. But nature was right here

Illustration/Uday Mohite

![]() In the solitary, quiet months of the first lockdown, my closest companion was a tree. That jungle jalebi tree danced outside my window all the 16 years I lived in this flat. But it had lived here much longer of course. Because it spanned the windows of two rooms, it often felt like living in a tree house. Through daydreaming hours I watched rain droplets shimmy and shimmer on its svelte leaves. Its fronds would grow through the grill like fingers and I could reach out and pluck its spongy, red jalebi-shaped fruit—if the birds left any. That tree was always full of birds. Phlegmatic crows glistened in the morning sun.

In the solitary, quiet months of the first lockdown, my closest companion was a tree. That jungle jalebi tree danced outside my window all the 16 years I lived in this flat. But it had lived here much longer of course. Because it spanned the windows of two rooms, it often felt like living in a tree house. Through daydreaming hours I watched rain droplets shimmy and shimmer on its svelte leaves. Its fronds would grow through the grill like fingers and I could reach out and pluck its spongy, red jalebi-shaped fruit—if the birds left any. That tree was always full of birds. Phlegmatic crows glistened in the morning sun.

ADVERTISEMENT

Dozens of sparrows, busy, like cartoon housekeepers. Parrots would swing upside down, or whoosh past like arrows in mythological dramas. Golden orioles, dapper with their slick black stripe, could be spied through the web of dark green, their distinctive trill bouncing off the leaves. Red-eyed koyals drove me cuckoo with their metallic calls before dawn. Once I saw a white-throated kingfisher.

Occasionally, excitingly, red-vented bulbuls would come perch on the grill for a quick minute and purple and yellow sunbirds would hop on to my flowering plants for a sip and a peck. March meant lemon yellow butterflies would float along its tendrils, seeming miraculous, though they are the commonest butterflies. At the risk of sounding like a nut that does not grow on trees, I have to say I was somewhat in love with that tree. People were busy posting about “nature coming back”. But nature was right here.

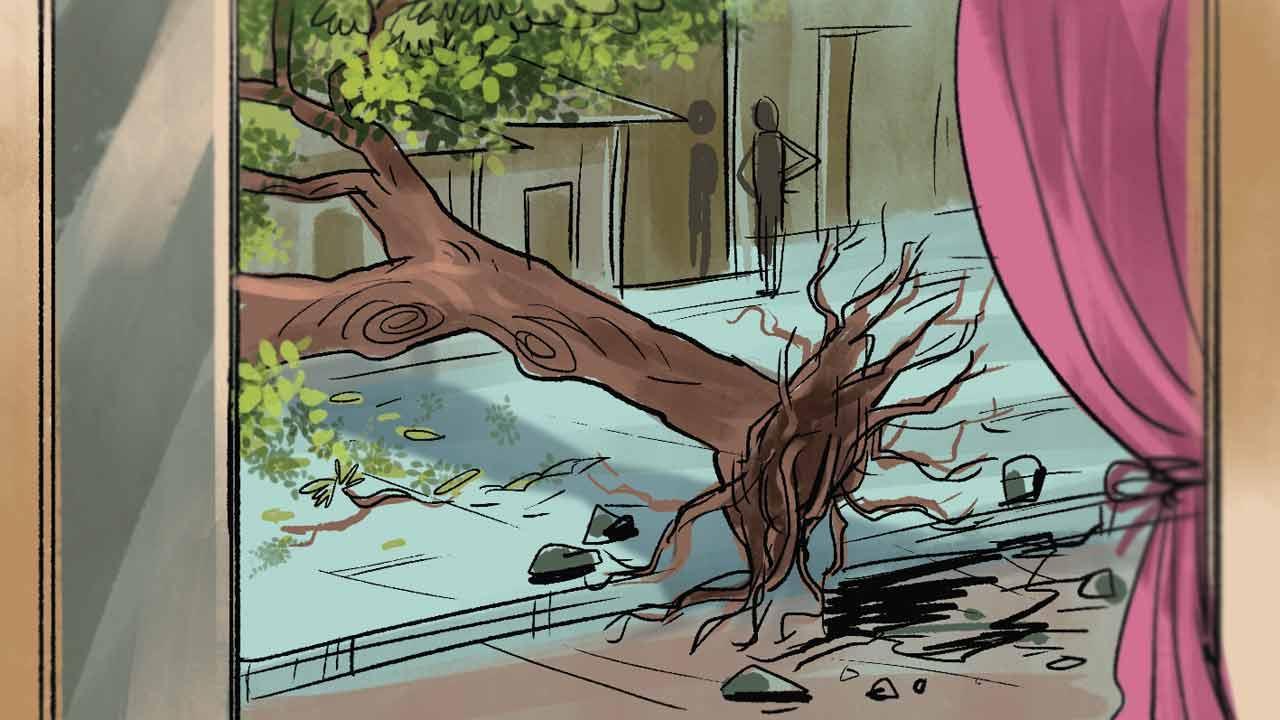

Some nights ago, I was woken up by a crash? An explosion? I couldn’t tell. I felt weirdly disoriented. Then I realised I could suddenly see the sky from my window—because the tree was missing. Getting up, I saw that the tree fallen over, sprawled, roots out, over the basti roofs below. There was alarm and commotion. It was ascertained that no one was hurt. Some roofs were damaged. The tree was dead. Its roots just didn’t have room to grow with all the concrete around.

It took many days to accept this vacuum, to try to appreciate the beauty of the Homeric rosy fingered dawn and not resent it for being my view instead of the tree. That one tree was a revelation and an education for me. Living alongside it helped me understand why nature is wondrous, and why it matters—because it is life itself, and keeps us living in so many different ways. It made me understand why biodiversity matters, very simply, and what is so special about the ordinary, as opposed to the spectacular Nature of movies and resorts. As Ed Yong, writer of An Immense World said in a recent interview, “Things don’t have to be better than us to be extraordinary… they are worthy in their own right and they’re worth protecting and saving in their own right.”

How dense and immense was life in just one tree. Imagine what would be lost if 2,700 trees are cut in the Aarey forest—leopards, insects, butterflies, birds, rivers and delight. People who call that forest home. These things are worth learning from, fighting for. The joyful movement to Save Aarey is worth supporting. Nature is here. Why send it away so it needs to “come back”?

Paromita Vohra is an award-winning Mumbai-based filmmaker, writer and curator working with fiction and non-fiction. Reach her at [email protected]

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!