Ruth Padel’s poems resist easy truths, demanding deep engagement with layered images—one moment decoding a mother’s weight, next observing a figure in a miniskirt, and then marvelling at a swirling Shakti image

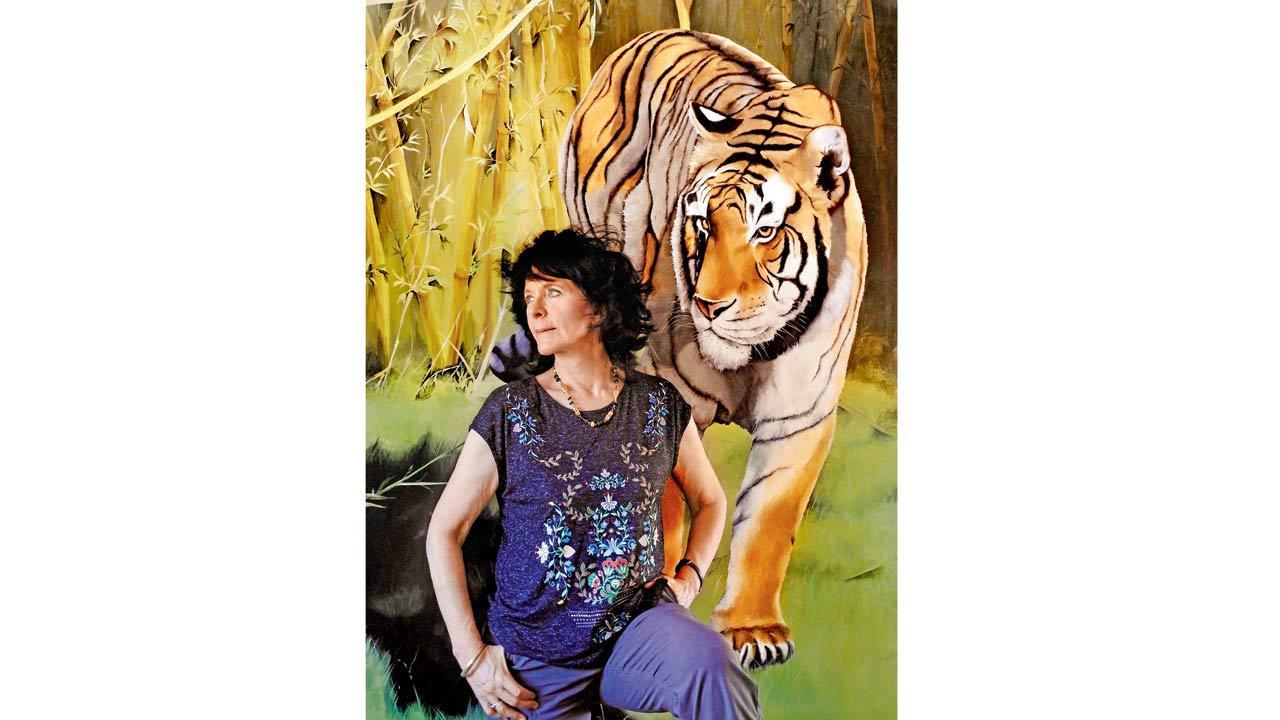

Ruth Padel’s earlier work, Tigers in Red Weather: A Quest for the Last Wild Tigers (2005), chronicled her travels across Asia, blending conservation and poetry to explore the endangered status of tigers. Pics courtesy/Ruth Padel

![]() On days when your energy is low, steer clear of Girl, Ruth Padel’s freshly released poetry collection published by Chatto & Windus. This isn’t the kind of book offering simple girlhood positivity quotes with a bit of political posturing sprinkled in. Instead, it is packed with vivid imagery—little smiling footballs with wings, a bullman lost in fantasy corridors, a snake slithering up a moon-coloured arm, and Death herself draped in a red-gold shawl. Her poetry paints colliding worlds—a world hostile to women’s autonomy, alongside a kundalini goddess force rising through a girl’s spine.

On days when your energy is low, steer clear of Girl, Ruth Padel’s freshly released poetry collection published by Chatto & Windus. This isn’t the kind of book offering simple girlhood positivity quotes with a bit of political posturing sprinkled in. Instead, it is packed with vivid imagery—little smiling footballs with wings, a bullman lost in fantasy corridors, a snake slithering up a moon-coloured arm, and Death herself draped in a red-gold shawl. Her poetry paints colliding worlds—a world hostile to women’s autonomy, alongside a kundalini goddess force rising through a girl’s spine.

ADVERTISEMENT

Padel’s poetry is work—crafted for deep engagement, asking for an investment of time, bandwidth and imagination, offering no room to coast, and embracing multiple themes within themes. Girl (128 pages, 46 poems) reflects the complexity brought to the fore by a poet-novelist-naturalist-scholar-wildlife advocate who seamlessly integrates her experiences across disciplines, geographies, and histories into a cohesive poetic narrative. Though born and based in London, her poetry spans diverse terrains. She has written about composer Beethoven and her great-great-grandfather, biologist Charles Darwin. In We Are All from Somewhere Else, she blends prose and poetry on the issue of migration. Her novels cover a wide range: one intertwines personal narrative with Holocaust history in Crete, another draws from her work in wildlife conservation in India.

In the poem Fair Verona, Padel captures tourists crowding Juliet’s balcony in Verona, Italy; hands reaching for the statue’s breast—a gesture that feels more like a violation than homage

In the poem Fair Verona, Padel captures tourists crowding Juliet’s balcony in Verona, Italy; hands reaching for the statue’s breast—a gesture that feels more like a violation than homage

Currently, Girl’s promotional tour will bring Padel to India, and she is also working on a major book about elephants, for which she has travelled to jungles in India, Sri Lanka, Borneo, and Thailand. Her research focuses on evolution, psychology, and behaviour in both wild and captive elephants. This project echoes her earlier work, Tigers in Red Weather: A Quest for the Last Wild Tigers (2005), in which she chronicled her travels across Asia, blending conservation and poetry to explore the endangered status of tigers.

Girl’s journey is both personal and expansive, stemming from two poetry commissions. The first 15 poems, which form the beginning of the triptych, were written for a baroque violin concert in Ireland, allowing breaks for the violinist to restring. Padel aligned these poems with the beads of the Catholic Rosary, used for meditations on Virgin Mary’s life. This parallel brings in the significance of the teenage girl—resilient and pillar-like—in stories across cultures. Padel resonates with the Virgin’s journey as a young mother who endured loss and was reunited with her son in heaven. “Belong is not the word/your child belongs with himself,” she states in the poem You Lose Him You Find Him.

Padel, who does not profess Catholic faith, acknowledges that her readers need not share an awareness of Christian imagery. Her poems are intentionally open to interpretation, embracing the belief that “poetry is freedom”—for herself and readers alike. She delights in readers who bring their own associations to her work. Padel, having taught ancient Greek at Oxford, reflects on her studies of poetry from this era and notes how eminent texts can enrich any reader, even when the original references remain beyond easy grasp.

For Padel, poetry also stems from distinct projects which she is a part of. For instance, the second set of 15 poems (which shape the last part of the Girl triptych) was commissioned for the Many Lives of a Snake Goddess project led by three women archaeologists who, like Padel, had lived and worked in the Knossos bronze age site in Crete. These new-age researchers challenge Victorian-era biases and critically examine Sir Arthur Evans’ piecing together of figurines as per his “snake goddess” theory, revealing how he imposed interpretations without strong evidence. This connection intrigues Padel too—just as Mary’s life was determined by a divine plan, the ‘goddess’ was reconstructed by a male Victorian archaeologist. As her poem, titled When a Man Looks at a Woman Wrapped in Snakes, states: He has done his best to remake her/ He strokes the iridescent glaze like touching a peeled fleck of sky once crusted with earth/ His faith in a single Great Mother is a cry he has kept inside him all his life.

It is interesting that the central panel of the anthology, situated between the Virgin Mary poems and those on the snake goddess, was written last, at the editor’s request. “My editor Sarah Howe liked the two sequences but asked for a more personal bridging section, which ultimately became the lyrical heart of the whole book, titled Under the Flesh and Dream of Who You Are is the Truth of Who You Are,” she says. The “truth” in these poems emerges from what Padel terms “the scaffolding of thought and life experience”, which holds memory, travel, relationships and, not to forget, a rethink of some normative definitions. In Definitions in the Urban Dictionary, Padel critiques how a girl is often reduced by male fantasy to an “amazing package that comes in differing flavours”. She highlights the absurdity of some believing “a gender called girls exists because online games allow them as characters”. She underscores the pervasive and distorted views about women in the digital world: “If you think an avatar’s really a girl, Guy In Real Life sets you straight”. Padel is concerned about men revelling in an open validation of misogyny.

When Padel looked up “girl” in the crowdsourced Urban Dictionary, she sensed the deepening of the troubling attitudes toward women. This columnist also explored varied dictionaries, including Marathi and Gujarati, to see the results.

Most definitions of “girl” robbed her of authority or maturity—often linking the term to appearance and youth. In Marathi, the term mulgi (girl) is tied to virtues such as obedience and modesty; in Gujarati, gagi or dikri come loaded with familial expectations. The widely recognised Marathi phrase “Mulgi Shikali, Pragati Zali” (If a girl is educated, progress follows), often championed in education campaigns, subtly frames women’s education in a utilitarian light—where a girl’s worth is measured by her contribution to nation-building. While there’s no harm in building a nation, the well-being of the builder shouldn’t be an afterthought.

Padel’s personal poems include reflections on her family lineage. She recalls “being a girl” in her grandmother’s house; her grandmother was the granddaughter of the famed naturalist Darwin. The poem transitions from the house to the garden, and then outward into nature: “I could explore anywhere, into fields past the danger-swirl of bees by the shed.” In later poems, she envisions her mother in various forms: “thirteen in a swimsuit on a stony beach” and “weirdly demure, looking down in a high-necked blouse and late Forties hairdo.” At times, she feels girlhood is a baton passed from her mother to herself and then to her daughter. She recalls her daughter first as an infant, then as a self-doubting teenager (“How am I supposed to be? / Is the boy I like the right boy?”), and later, as an adult going to work in a conflict zone (“Great. You’re off to Colombia to protect campesino families from paramilitaries.”)

Padel shares her wonderment over the exact chronological age when a girl becomes a woman: A “girl” can mean an infant, but also anyone up to 30, perhaps even further? Can we ever stop feeling like the girl we once were, she wonders. Padel worries about girls’ safety, although she knows: “But the world needs girls. That’s the deal. They have to explore.”

The poet’s work confronts the persistence of misogyny in the First World as well as developing countries. From Delhi to Delphi, unsafe streets feature in her work.

In The Old Tin Can, she illustrates the Saturday night tension in Camden, where young women walk with caution, clutching their phones, surrounded by the constant clang of a “loose tin can” in the background—a haunting male dominance in public spaces.

Fair Verona is a poem that resonates with this writer personally. Padel captures tourists crowding Juliet’s balcony in Verona, Italy, their hands reaching for the statue’s breast—a gesture that feels more like a violation than homage. Her image of “hand after hand…polish[ing] her breast to soft electric gold” reflects a crazy side of tourism, where reverence is replaced by selfies. In my own 2015 visit to Verona, I saw a similar scene—a token of love reduced to a photo op. The Girl reminded me of what’s at stake when we turn a symbol into a spectacle.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at [email protected]

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!