A recent exhibition inspires musings on a fistful of women bequeathing both personal and professional influences

Malati Jhaveri with Tenzing Norgay (right) and Sherpa Ajeeba

She got me thinking. When Neeta Premchand recently walked us through her curated show on early feminists of Bombay Presidency, the mind flew to recollections of women I have been blessed with in my life. Perhaps less epic than the legends featured on the walls of the CSMVS Museum, here are the first four names that cropped up.

She got me thinking. When Neeta Premchand recently walked us through her curated show on early feminists of Bombay Presidency, the mind flew to recollections of women I have been blessed with in my life. Perhaps less epic than the legends featured on the walls of the CSMVS Museum, here are the first four names that cropped up.

ADVERTISEMENT

‘Aa sheher ni khoobi toh jo’

I miss those kohl-lined eyes flashing bright beneath her trademark big, bright bindi.

Among Bombay’s more iconic figures, she was one of its oldest freedom fighters, as well as a theatre thespian, textile conservationist, ace photographer, mountain trekker and nature lover. Serendipity gifted me the chance to interview multi-faceted Malati Jhaveri in all these avatars.

I could drop in on her any hour of the day without asking, “Will you be resting?” Despite painful arthritis, noon naps were strictly no-no—they cut into hours spent meticulously translating classics from Hindi to Gujarati. My nonagenarian inspiration finished 20 such books, taking the occasional break.

Jailed three times in 1942 alone, on August 8 that year, she, ironically the daughter of the silk merchant Sir Shantidas Askuran, draped a red khadi sari given to volunteers attending the explosive Congress session at Gowalia Tank. Teargas was released for probably the first time in India. When a piece of shell fell on her, she lobbed it right back at a British soldier. Burnt but triumphant, she was whisked off to jail, but managed to even win police sympathy on bursting into nationalistic songs.

A similar rootedness saw Malatiben tirelessly promote indigenous textiles. Her sister Prabha Shah and she ran the Sohan Sahkari Sangh, a pioneering effort in the non-government sector to create a thriving market for handlooms and handicrafts. They did this for 40 dedicated years with a combined rare sensibility for discerning and developing design within the rural cooperative network.

Also read: A case for embracing failures

An abiding passion was theatre. The constitution of the Indian National Theatre (INT) was inked in prison by patriots like her husband Damu Jhaveri, Chandrakant Dalal, Rohit Dave and Mansukh Joshi. Malatiben introduced me to the repertoire of INT stage stalwarts from Adi Marzban to Burjor Patel. “We are two communities with great talents, besides a common language, Gujarati and Parsi drama made magic together,” she said. “Aa sheher ni khoobi toh jo—how special this city is. You really must keep writing about it.”

Another book that took me to her was an oral history of the Sherpas from Darjeeling. Her Shanti Sadan apartment at Babulnath hosted the brave climbers who taught courses in 1950s and ’60s Bombay. I remember a refrain. She often liked to say, “The sherpas are loyal to their last breath. They don’t make men like them anymore.”

Nor women like you, Malatiben.

‘Sharpen the Marathi, enjoy your city’

The older I get the more I resemble my mother, I’m told by those of her generation I’m privileged to still interact with. The prouder I feel. Kind, practical, the perfect no-nonsense partner to her dreamer husband, Homai Dastoor held together a joint family with good sense and grace. This, despite its unusual dynamic. Three of dad’s unmarried sisters lived with us till the end of their days—closer to our grandmother’s age, because he was the youngest of eight siblings.

Homai Dastoor with baby son Phiroze

Homai Dastoor with baby son Phiroze

With seven people to cook meals for in a large, rambling home, mum found hours to beautifully sew her clothes and mine, enjoy a wide friends’ circle and pack in other activities amazing my brother and me. Enrolling for twice-weekly New Math and Marathi classes, she became a self-appointed conduit, directly demystifying this pair of subjects for us. Saving us the trudge to tuition teachers and the family some money. We learnt with her and ran off to play in Almeida Park down the road.

Encouraging our house help Vimal’s kids to study in peace at our place, away from disturbing interruptions from drunks and pimps populating their rough shanty beyond the bazaar, she served a daily evening snack with milk and asked in return that they respond only in Marathi while we spoke in English. All of us benefitted from the simple brilliance of the idea helping pick up each other’s language.

To prevent the barter slip to being boring, Mummy kept the arrangement fun-flowing. She engineered this with subtle strategising. Spotting me read a review of Manmohan Desai’s action saga, Dharam Veer, she suggested Vimal’s daughter Meena narrate me its story in Marathi. What ensued was a most exciting rendition of Dharmendra and Jeetendra’s exploits in that blood-and-thunder 1977 screen spectacle.

“Sharpen the Marathi, enjoy your city,” mum urged. From “Listen to what the cobbler is saying to his customer” to “Next week, the rain will sweep away these gulmohar flowers”, she thrust meinto the buzz and thrum of everyday life as we walked summers through the zigzagging Bandra lanes around Hill Road.

Thanks ma, for pushing me toward the twin joys of local lingo and quick perception. They have blended beautifully, meaningfully, to enhance my experience of a city that isn’t always easy to love.

‘There’s someone for everyone in Bombay’

Ours was a wholly remarkable relationship. Lulu Mehta worked with my father half a century ago at Bombay House—she in public relations, he in Tata Textiles—and then with me at Marg Publications in the 1990s. When I’d visit dad at the office after school on Fridays, she never let me leave without pressing a foil-wrapped chocolate fish from RTI in my hand, whispering, “Some mitthoo sagan, for luck to our little girl.” Twenty years later, she did the very same for my kids, except she turned up at home on their birthday and Navroze mornings bearing small boxes of mawa ni machhi, “because their generation eats too much chocolate anyway”.

More mother than colleague, she fussed endearingly through my pregnancies, though I’d mock-protest, “Stop spoiling me.” The firstborn was at risk of emerging feet-forward in a breech birth if I did not engage in certain bent-over asanas to lock the tiny head correctly south. With less than a month to delivery, these were doc-recommended thrice a day. How to manoeuvre such impossible, unprofessional moves in the middle of the editorial room, I fretted. Trust Lulu to stand guard at its door, for my privacy and comfort. She also insisted on regularly plying me with her homemade “ghau nu doodh”, a traditional blancmange-like pudding supposed to build solid baby bones. Choosing her tenderness over the tastelessness, I gulped down portions.

Single, sensitive, ever interesting, Lulu was outward-oriented, if a bit opinionated. You never guessed she lacked family of her own, the way she reached out, related to and stayed in touch with people. Of modest means, she unfailingly remembered individual tastes as she exchanged books and notes on music concerts, cheered up the unwell with her sprightly presence, and participated in friends’ glad and sad moments with an attention that redefined the words “love” and “care”. Neighbours in her Tardeo block of flats always dropped in to check on her. “Have faith. There is someone for everyone in this city,” she’d say jauntily when we worried about her.

‘Stay curious, find out’

These were her buzz phrases, which I’ve made mine. She is a major reason why I write this column. Who else but Sharada Dwivedi so exquisitely scrutinised and shared the untold delights of a beloved city from pre-colonial to present times.

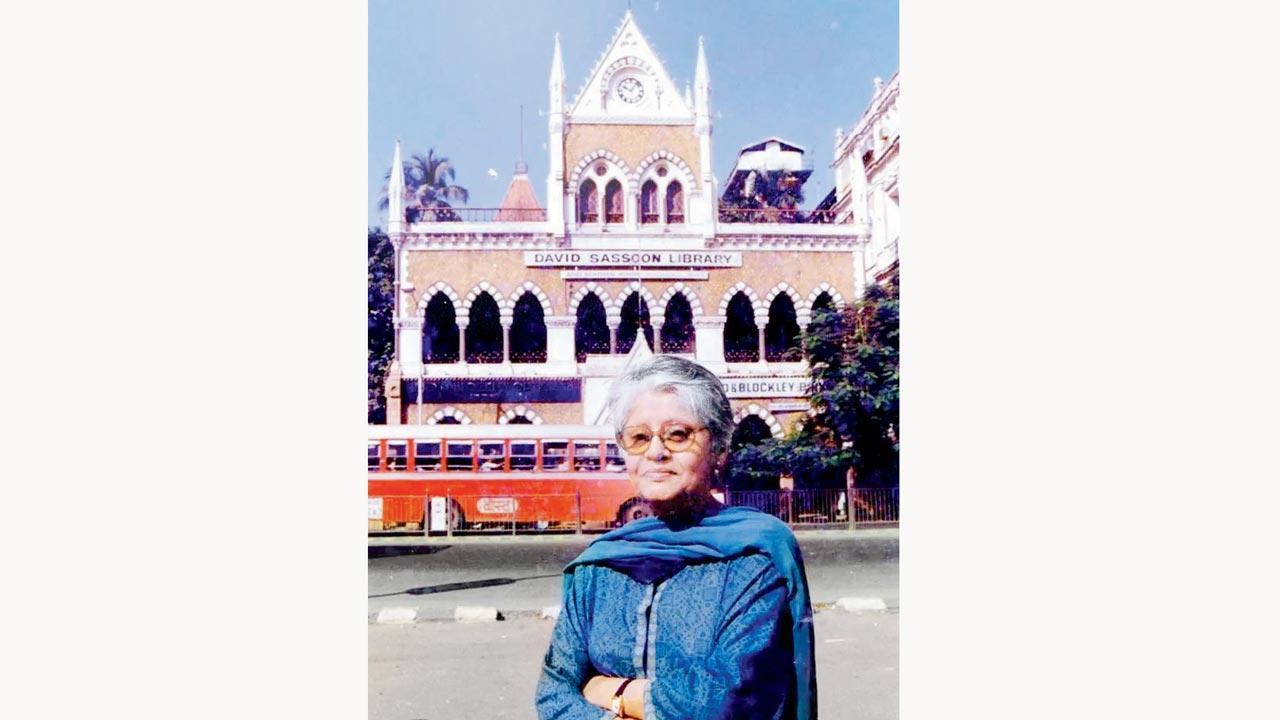

Sharada Dwivedi at Kala Ghoda

Sharada Dwivedi at Kala Ghoda

Moons ago when Lintas commissioned me to start a features magazine for ITC, she and Rahul Mehrotra contributed essays for the inaugural edition. Interacting on hers, I discovered she knew my father quite well. GS Mhaskar and Co, her family firm at Dadar, was a stockist of Tata Textiles, the firm he was with for almost 40 years. “How’s Homi?” shot the fond question the minute she hugged me.

That affectionate connection apart, I grew to respect her rigour of thought and hope to have absorbed, not just appreciated it. Campaigner and chronicler extraordinaire, she crisply condemned dial-a-quote journalists whose lazy insouciance spelt disaster in print. “They should call themselves misreporters, not reporters!” she fumed. Lucky for me, she did offer information on the phone, freely and fully engaged with whatever I worked on. “Stay curious, find out,” she constantly advised.

Here’s looking at you, Sharada, up where you are in the celestial firmament above. No doubt mapping niches there for those fortunate to follow your favourites on earth.

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at [email protected]/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!