Going into just one candidate in one constituency to figure how complex extrapolating it to an entire election could be

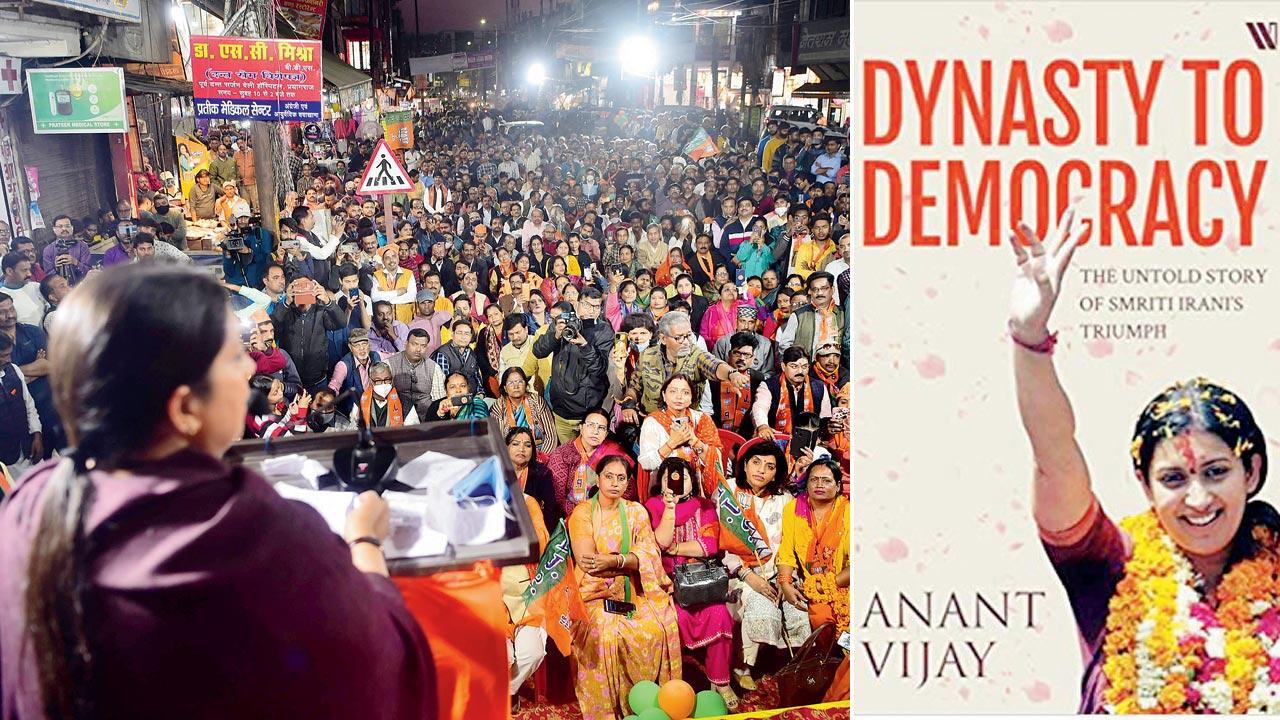

Union minister Smriti Irani at an election campaign rally in Allahabad ahead of ahead of Uttar Pradesh Assembly polls; (inset) cover of Anant Vijay’s book. Pic/AFP

Audience/electoral’ democracy from a distance looks a lot like the box-office of movies. It’s primarily centred on a star. The marketing push is geared towards how a political party is up for a huge haul already.

Audience/electoral’ democracy from a distance looks a lot like the box-office of movies. It’s primarily centred on a star. The marketing push is geared towards how a political party is up for a huge haul already.

ADVERTISEMENT

Likewise the crores flashed in blockbusters’ posters. Which isn’t to reveal how much a producer’s made from a movie by now. That’s of no interest to the audience. It’s to announce how many people have watched that film. So should you. It’s the only one playing in town.

What’s the assumption here? That people outsource their choice to a majority. If so many are voting a certain way, signalling a supposed wave, why bother going the other way.

Only that an election, whether state/national, involves multiple movies/constituencies, with its own set of unique issues, somewhat homogenised by political parties, fighting against each other, for eyeballs/votes, across geographies.

While every movie is a Sholay before release, how does anybody tell the results? Pollsters seem to gauge the general direction of an election right, often—never quite the numbers. Sometimes they get both wrong.

Or so it seems from looking at a constituency, Amethi, in Uttar Pradesh, during one (general) election (2019), that journalist Anant Vijay does a deep-dive account of, in his book, Dynasty to Democracy: The Untold Story of Smriti Irani’s Triumph (Westland), translated from Hindi by Debdutta Bhattacharjee.

What was so great about BJP candidate Irani winning from Amethi in 2019? That, apparently, nobody had convincingly predicted? She beat the Congress boss-man Rahul Gandhi, who she had fought against in 2014—entering the fray about three weeks before the vote. She had narrowed Rahul’s victory margin in 2014; but lost.

As a Union minister, Vijay writes, she kept returning to Amethi, after the 2014 loss—addressing local issues, such as timely delivery of rakes of fertilisers, or setting up soil-testing labs for Amethi’s farmlands.

Vijay’s book almost entirely captures one perspective—that is the victor’s, of course; and that’s how history gets written anyway. Why was Irani’s victory symbolically historic? Certain constituencies in India—like Baramati in Maharashtra for Sharad Pawar—get singularly associated with a person whose traditional sway among voters is complete.

Amethi’s the clichéd Nehru-Gandhi family bastion/fortress. So much so that other Gandhis—Rajmohan, grandson of Mahatma; Menaka, wife of Sanjay, who adopted Amethi first—have contested from the constituency, claiming to be the ‘real Gandhi’ after all. They were conclusively defeated by former PM, Rajiv Gandhi (MP from Amethi, 1981-1991), father of Rahul, who in turn held the seat for a decade (2004-2014).

Rajiv’s years would’ve involved voting in ballot boxes, upturned, mixed, and then counted. Which isn’t the case with electronic voting machines—where I guess, you can instantly tell which polling booth, among Amethi’s 1,963, voted for whom. I wonder what that does to the principle of secret ballots.

Each polling booth in Amethi, as Vijay details, had 20 workers assigned by the RSS, BJP’s parent, parallel network of volunteers (swayamsevaks), which had stationed itself November, 2018, onwards.

As I suppose with other such constituencies, the RSS maps Amethi into districts (two), khands (seven), mandals (93) and nyay panchayats (116). The swayamsevaks belong to shakhas (local branches), which increased from 250 in 2014 to 300 in 2019. There is no official procedure to become a swayamsevak.

There are also recreational/team-building exercises/games played inside shakhas, like ‘Mein Shivaji’, ‘Mitra raksha’. One such game that had an effect, Vijay cites, is called ‘Dilli hamari’.

It involves a swayamsevak standing inside a circle, repeatedly shouting, ‘Who will win Delhi?” In a merry-go-round of sorts, or that’s what I understood of it, other participants try to enter the circle, shouting back, “Dilli hamari!”

Another move that apparently caught the attention of local, married women was Irani organising a mass fast, Durdariya vrat, in honour of a local goddess, Aosaan Maai.

Yet another one, Vijay writes: “[Irani] learnt that during the revolt of 1857, Bhale Sultan of Umra village had posed a challenge to the British. She became the first candidate from Amethi, in the history of independent India, to visit Umra and commemorate Bhale Sultan.” Segueing into movies still, I see from her list that she also organised a free screening of the war movie, Uri.

This is called a ‘campaign’—a word that, outside of elections, is used for war, and advertising. A memory from the UP state election campaign in Prashant Jha’s book How the BJP Wins (Juggernaut) is Prime Minister Narendra Modi referring to himself as the ‘senapati’. As the old adage goes, “Half of what we spend on advertising is a waste. Except, nobody knows which half.”

Beyond the box-office like blitzkrieg for a political party, in a fresh and fair election, surely among voters, there are complicated issues, both personal and public, ethnic plus economic. Here, we’re talking about only one candidate’s arithmetic (Irani’s 49.7 per cent votes against Rahul’s 43.8), and chemistry, in a constituency (of about 1.5 million voters), in an election.

Extrapolate that to multiple parties/people among hundreds such constituencies to figure its complexity. You’re not surprised Delhi-based top journalist types hardly ever get anything new right about an election beforehand. They probably follow politics. Not so versed in micro-management plus mass mobilisation, perhaps?

Mayank Shekhar attempts to make sense of mass culture. He tweets @mayankw14

Send your feedback to [email protected]

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!