The cruel and unforgiving years in Bombay bolstered firebrand trade union leader George Fernandes to take up the cause of the working class. A new biography reveals his early struggles in the city of dreams

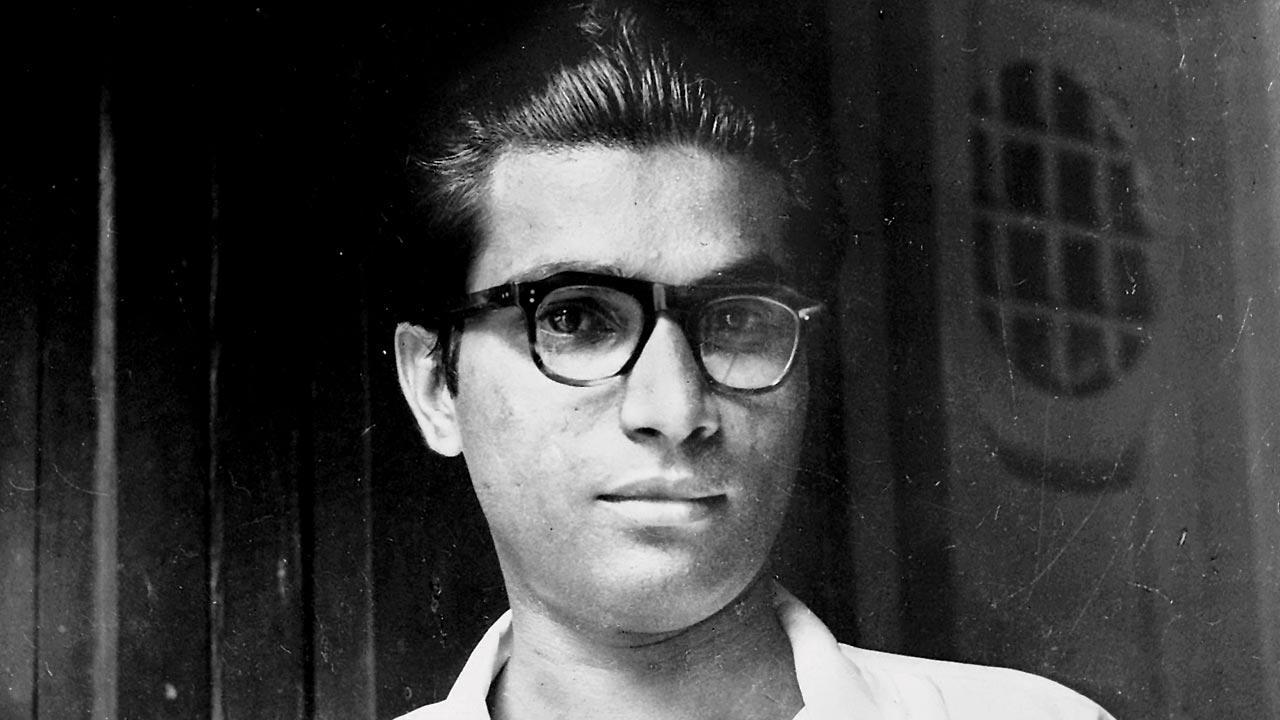

George Fernandes on the eve of founding of the Municipal Mazdoor Union in 1955. He was fond of cars and movies, and even in those conservative times, had love interests. Pics Courtesy/Fredrick D’Sa, Bombay Taximen’s Union

One rain-drenched day in August 1950, a twenty-year-old George arrived in Bombay. He had left Mangalore just when it had appeared he was beginning to discover his moorings there. But he broke away from them abruptly and completely, carrying the essence of inheritance alone as his baggage to the new city. Mangalore’s hotel workers provided for his journey. As a formal send-off, “the hotel workers organised a meeting in Maidan and gave me R20 and a bus ticket to Kadoor, from where one took a train to Bombay”.

ADVERTISEMENT

They advised him to study further, become a lawyer and return to serve them. But he didn’t become a lawyer, nor did he ever return. “I let them down,” he would tell Himmat one day, “not because I wanted to, but because Bombay was very cruel to me in the beginning.” As initiations are seldom not brutal, he explained, “I had no money. I wanted a job, any job, very badly. Without the job, I could neither live nor study.” These everyday torments of a recent migrant were recalled many years later when he was girding his loins ahead of his first Lok Sabha election campaign in 1967. As it was an experience in a conquered past, it is doubtful if he was not venting to make an effect; after all, Bombay was a city of migrants and he, one of their own, was now challenging SK Patil, a seemingly unshakeable fixture in its politics. That urge in him, however, could not obscure the spirited courage with which he had moved out of Mangalore. That venture conveyed a determination far more powerful than the desperation of a migrant escaping poverty. Beneath the temerity of his scheme lay hidden the implacable resoluteness of his will and a raw ardour. Far from being a hungry migrant fleeing the hinterland, he was a lad pushed out by the exuberance of a life already lived among the toiling people.

At the beginning of 1963, Fernandes was campaigning for supporting the war effort by requesting the working class to make liberal contributions to the war fund. Here, George is seen addressing the BEST workers with BEST Workers’ Union’s Sobhna Singh on his left

A couple of months before his departure, he had been in the thick of the transport strike organised in February under the leadership of [Placid] D’Mello. In July, he was at Madras, along with Ammembal Balappa, as delegates representing their district, soaking in the proceedings of the eighth National Conference of the Socialist Party. And, then “a few weeks later, I left for Bombay”. As a matter of fact, it was quite a bland statement, not revealing what made him suddenly decide on Bombay. A clue, however, seems to lie in his meeting C Gopala Krishnamoorthy Reddy (1921–94) at Madras where they both had been to attend the national conference of the Socialist Party. Ten years senior to him and about the same age as D’Mello, CGK had started his career in Bombay and had been distantly associated with the socialist trade union movement active there before he moved to Bangalore to work as the manager of a newspaper enterprise. He was involved in the Mysore unit of the Socialist Party and gingerly took part in party deliberations at the national level. They found much in common, as would still be clear some 25 years later when CGK sought him out in hiding and they worked together in the underground resistance to the National Emergency. Spurred by the experience of the transport workers’ strike, it is entirely possible they exchanged notes, and George asked for his advice about his future course. CGK might have suggested or, more plausibly, steeled George’s nebulous idea of going to Bombay to work in the organisation of labour there. Bombay then was not just India’s leading industrial site and a commercial and financial hub, but it had also become a “most dramatic centre of working-class political action”. Nothing that was done in its factories remained within them—its message invariably went deep and wide beyond and acquired national prominence. Further, chairing the Madras conference was Asoka Mehta (1911–84), famous for his work among the labouring class, and who soon after would spearhead a textile millworkers’ strike in Bombay. And, adding to the excitement, George knew that D’Mello would return to Bombay once released from jail.

Thrown out of the Socialist Party office, George went to the “footpath opposite the Central Library” and took to living there. Bombay was the favourite hunting ground for the people from his region in search of a livelihood. The Bunts had a flourishing share in the city’s eateries, running the ubiquitous Udupi hotels. Living in the vicinity of his pavement dwelling was a family of Mangalorean descent, running a corner shop selling some eatable items and cigarettes. The lady owner lent him a rug to stretch out on. She occasionally provided him with food too. “She looked after me,” he would remember in gratitude 60 years later. “The nights of these terrible months I spent sleeping on the various footpaths,” he told Himmat. In the mornings, he roamed around the business district “aimlessly, subsisting merely on chana (peanuts) and municipal water”. There were quite a few cinema halls in the area.

On the advice of kindred people, he approached them for work. He also approached restaurants and hotels. “I started going from hotel to hotel. I had been told how to ask for a job: ‘Seth, nowkri hai kiya?’ Everywhere it was the same refrain: ‘Chalo’ (get lost).” He wanted “a job, any job”, but it was proving painfully elusive. “All his knockings at doors were in vain,” he would write a year later, recounting D’Mello’s experience in 1935 when he had first come to the city looking for work. “His fate also was that of thousands of others, a lot of them more learned than himself.” The words he wrote for D’Mello befitted his travails too. Then someone, again a Mangalorean, suggested he approach the Times of India. He did, and got the job of a proofreader, helped by his felicity in the English language. He had no money to buy a dictionary or thesaurus, but discovered an ingenious way to overcome the limitation. There were bookshops lining the road in the vicinity of Victoria Terminus. When in doubt about a particular word or a phrase, he would rush out of his office and head for one of those, refer to a dictionary and run back to his working desk. In a slow, incremental way, life began to roll on, even if it was seldom without pain.

Excerpted with permission from The Life and Times of George Fernandes by Rahul Ramagundam, published by Penguin Random House

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!