Indian dolls look like us, dress like us, and tell stories of our glorious past. But because their artisans lack market savviness and trend awareness, they are being inched out by their American cousin

An exhibit at Shankar’s International Dolls Museum, New Delhi, depicting a Rajasthani Bride

If Barbie could talk, she’d probably be thrilled about how well she’s doing in India these days. And why not? She’s got a new wardrobe crafted by renowned fashion designer Anita Dongre, and she’s showing up to Diwali parties in a bedazzling ‘moonlight bloom’ lehenga-choli adorned with the lotus, ready to win shelf space in toy stores across the country.

ADVERTISEMENT

Laiphadibi of Manipur; Diwali Barbie by Anita Dongre; Diwali Barbie by Anita Dongre

Laiphadibi of Manipur; Diwali Barbie by Anita Dongre; Diwali Barbie by Anita Dongre

We have to admit, there’s something undeniably captivating about Barbie. Her allure comes from the understanding that she isn’t just a doll: she’s a brand, a lifestyle, and, for better or worse, a global icon of aspiration. After the success of last year’s movie, she’s made an unapologetic comeback, pinker than ever.

Artefakt’s paper mache dolls; The Pinklay Doll; Sawantwadi Dolls

Artefakt’s paper mache dolls; The Pinklay Doll; Sawantwadi Dolls

The Diwali Barbie is a shining example of globalisation wrapped in sequins. And in the shadows, India’s traditional doll artisans are quietly watching their craft fade. There’s an important question to ask: What happens to traditional doll artisans when a global powerhouse swoops in with glitzy, glamorous products? In a world dominated by mass production, marketing budgets, and slick online campaigns, how can traditional artisans stay afloat?

Doll collector Neha Parekh with her collection of dolls

Doll collector Neha Parekh with her collection of dolls

Let’s rewind to the 1990s, the era of liberalisation ushered in a wave of foreign products previously barred from the Indian market. “I think this was almost 15 years ago… India was going through this phase where all international products were considered superior, and even international travel was preferred over domestic,” recalls Yuvrani Shraddha Lakham Sawant Bhonsle of Sawantwadi Palace in Maharashtra, whose family is determined to preserve the art of Ganjifa, which are hand-painted playing cards that originated in Persia and were brought to India by the Mughals.

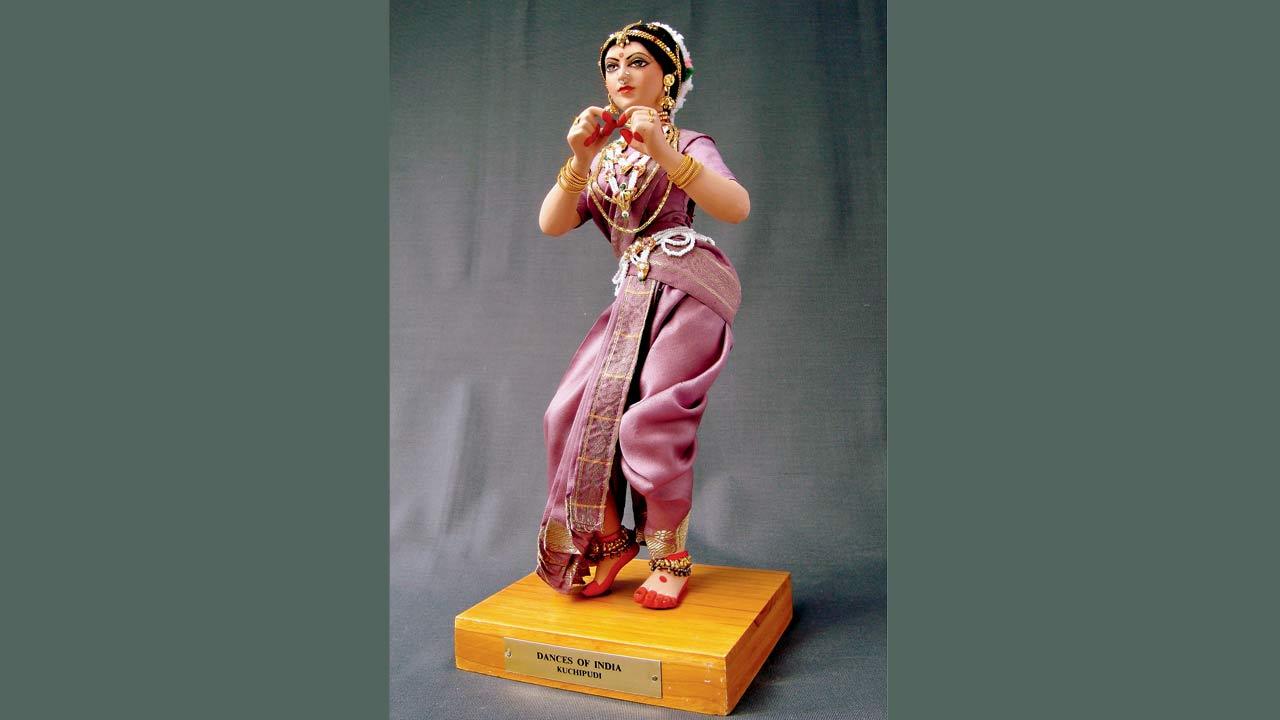

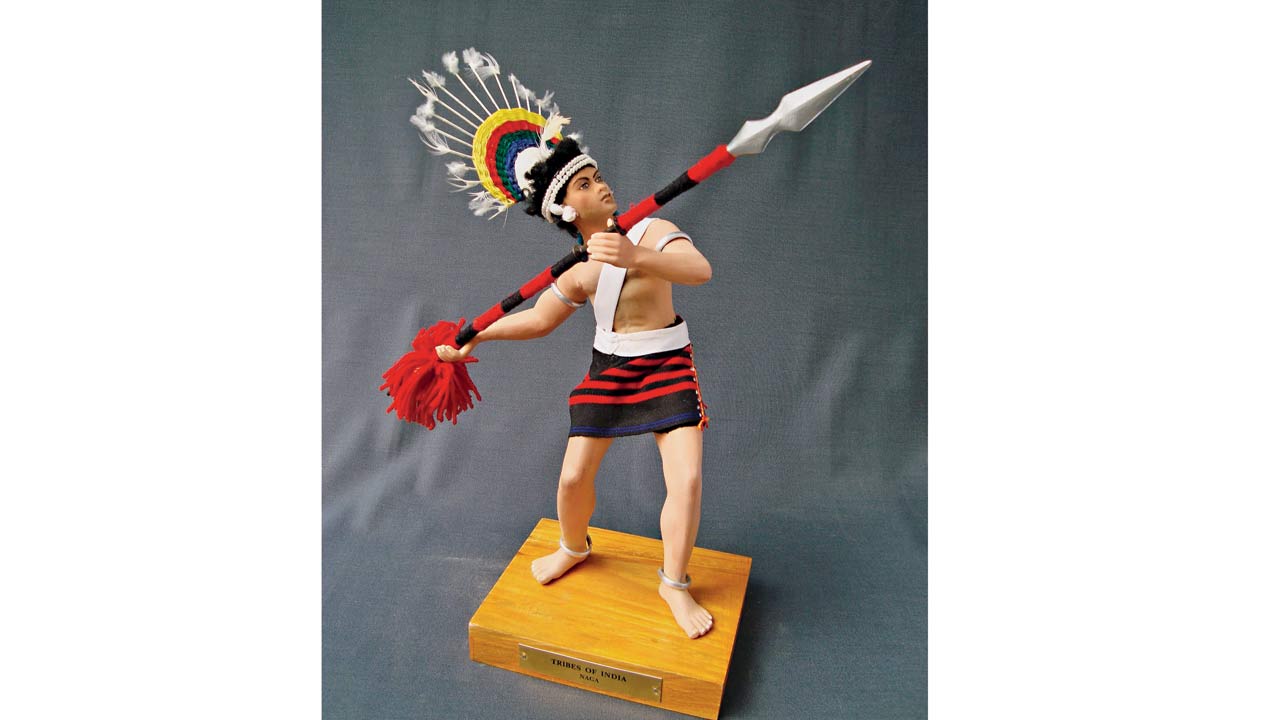

Exhibits at Shankar’s International Dolls Museum, New Delhi, depicting the Kuchipudi dance, native to Andhra Pradesh

Exhibits at Shankar’s International Dolls Museum, New Delhi, depicting the Kuchipudi dance, native to Andhra Pradesh

Barbie, introduced in India in the late 1980s, initially failed to gain traction. However, post-liberalisation, when everything ‘imported’ became chic, and thanks to Mattel’s joint venture with Blow Plast, Barbie was at the forefront of the Western influx.

But India’s love affair with dolls runs deeper. The indigenous ones from Manipur or Rajasthan are miniature symbols of cultural heritage, used to teach children about their roots, religion, and social values. “Our founder, the renowned political cartoonist of India, K Shankar Pillai’s idea” explains Mrs Navin Menon, in-charge of the International Dolls Museum in New Delhi, “behind setting up the museum was his desire to showcase to Indian children, through visual exhibits, different cultures of the world, the history and geography of different countries, the difference in the style of dress and so on”.

Ramani Yellapantula, founder of Artefakt, Nagpur

Ramani Yellapantula, founder of Artefakt, Nagpur

Established in 1965, Shankar’s International Dolls Museum has a collection of 7,500 dolls from 85 countries, and is the largest museum of its kind in the world. The museum started with Shankar’s personal collection of 500 dolls. Later more were added, the dolls being gifts from different Ambassadors in India. The Dolls Workshop, attached to the museum, was initiated to make handcrafted authentic Indian costume dolls after meticulous research, to give away as gifts in exchange for the dolls received.

More than a commercially viable plaything, dolls can be sociological representatives. Take the Kathputlis of Rajasthan—brightly coloured puppets made from wood and cloth used to tell traditional folklore. Or even the Taka Taki dolls of Sawantwadi. “There is a very interesting history behind these dolls” says Bhonsle, “They come in pairs and were given to young Maratha princesses when they got married. When the practice of Sati was abolished, these young women would sacrifice the Taka Taki dolls instead of themselves, which symbolised that a part of the wife had died with the husband.” Both the dolls, male and female, are equally tall. “That speaks to how queens and Maratha women have equal power and status in the family,” she says.

Traditional Indian dolls are slowly and carefully crafted

Traditional Indian dolls are slowly and carefully crafted

As Konsam Ibomcha Singh, a Padma Shri award-winning doll maker, explains, “Our traditional Laiphadibi dolls look like Manipuri girls, with enchanting, full moon-like faces and two dots for eyes. This reflects how we perceive ourselves.” Terracotta dolls, often associated with rituals, mysticism and even black magic in Bengal, further illustrate the diversity and richness of India’s doll-making heritage.

Prabhadevi-based doll collector Neha Parekh, who has over 1,000 dolls says, “Ninety per cent of my collection is sourced directly from artisans. The legends behind them, the folk stories, indigenous tribes, textiles, festivals, and cultural practices are a treasure trove of legacy.”

While these dolls carry profound meaning, they lack the one thing Barbie has in abundance: Global visibility, popular appeal and most importantly, mass production. Barbie’s genius lies in the fact that she isn’t just a doll. She’s a person, a character, a chameleon. Barbie is aspirational—she represents the idea that girls can be anyone they want to be. And that she’s the modern woman, blonde and Caucasian…

“Brands like Barbie have a diverse range of dolls that can help me spark a conversation with my child and ignite her imagination” says prominent mommy blogger Richa Singh, Co-founder and CEO, Blogchatter and Happinetz, “but she also represents aspirations, dreams, and individuality, which can be inspiring. This is a factor that I put a lot of emphasis on while selecting a doll for my children.”

The Pinklay Doll collection

The Pinklay Doll collection

In a country where festivals are equated with the shopping seasons, Barbie has another advantage. Her Diwali avatar, complete with a lehenga, appeals to parents looking for culturally appropriate toys. And Mattel knows this. The Diwali Barbie isn’t just a doll in a new, pretty outfit; it’s a savvy move to capitalise on a festival-driven consumer market. Traditional artisans can’t just churn out new designs to meet festive demand few times a year. Artisan-made dolls take time to be crafted individually. Barbie’s ability to adapt to trends—celebrating Diwali or dressing up for Halloween—gives her the edge in a market that demands constant novelty.

Not to mention the lifestyle you can build around just one doll, which is good for a corporation’s pockets. “International brands offer a lot of additional elements that make them appealing,” says another mommy blogger Avantika Bahuguna, Brand Consultant and Founder, Momsleague Global. “Dolls come with dollhouses, makeup rooms, or doctor sets, which adds to their allure. Our children like to create complete sets when they play with dolls, and added features, such as [being able to] change hair colour or turning the doll into a mermaid or doctor, provide a variety of imaginative options. These are things that local dolls don’t typically offer.”

Daisy Tanwani, founder of Pinklay. Pics/Kirti Surve Parade

Daisy Tanwani, founder of Pinklay. Pics/Kirti Surve Parade

While Barbie’s appeal is undeniable, her presence in the Indian market highlights a stark contrast between mass production and traditional craftsmanship. India’s toy industry is projected to reach US$ 3 billion by 2028, growing at a 12 per cent compounded annual growth rate (CARG). Dolls are a large part of this projection. According to a 2022 report published by the Global Trade Research Initiative, the current world trade of dolls and action figures is roughly US$ 12 billion. International brands such as Mattel can mass produce toys at a lower cost, making them more accessible to the average consumer, while handmade dolls take longer to produce and are therefore more expensive.

Daisy Tanwani, founder of Pinklay, which offers culturally inspired plush toys, explains, “The scale of handmade products will never match machine-made products. Pinklay dolls are slow, mindful production, and the idea is to not compete with the global, machine-made alternatives. The idea is to create a market for sustainable toys that create value for those who make them.”

Manipur’s Laiphadibi dolls

Manipur’s Laiphadibi dolls

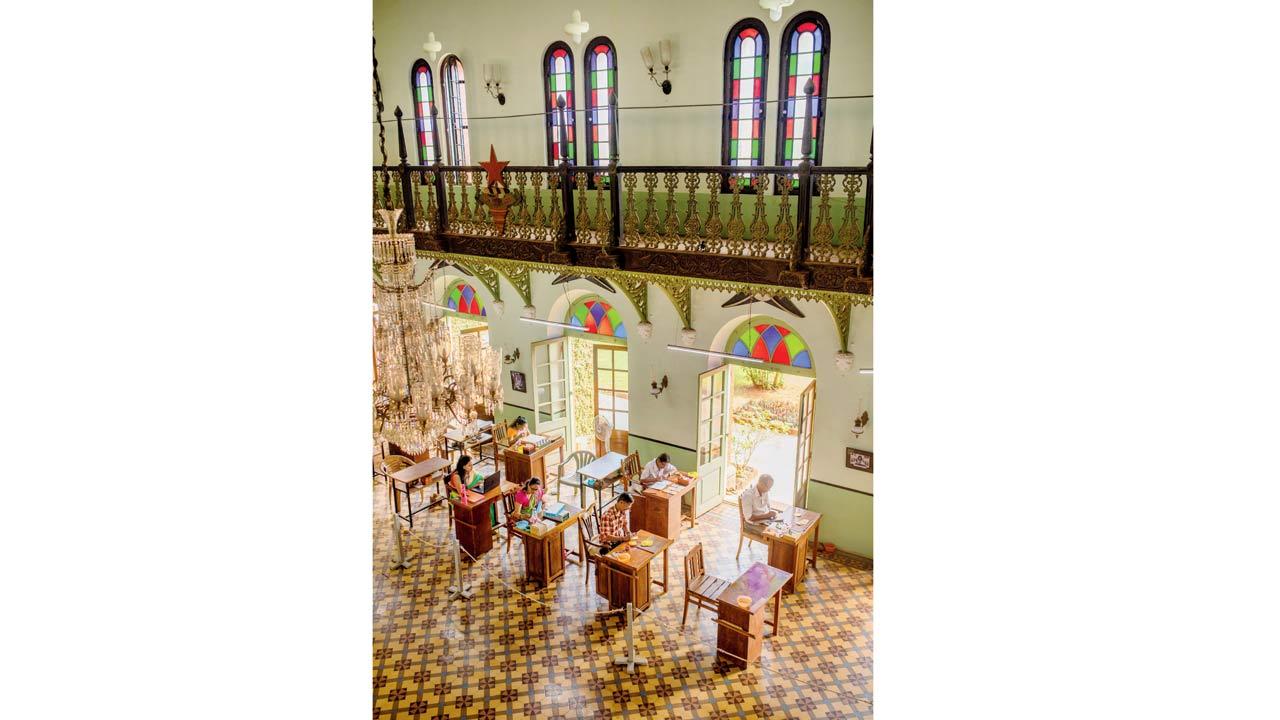

One way that Indian doll makers are trying to adapt to the modern market is by embracing e-commerce. For many of traditional artisans, e-commerce platforms have become a much-needed lifeline in an increasingly globalised market. With brick-and-mortar stores unable to generate the same kind of visibility as international giants, e-commerce platforms have opened up new avenues for artisans to market to a wider audience. Bhonsle shares how Sawantwadi Palace has made the shift to online sales: “Even though there are just 15 artisans on our team, we started working with platforms such as Reliance Retail and MeMeraki, and that’s helped us reach a larger audience.”

Social media, of course, is an agent of recognition. Instagram, Facebook, and Pinterest allow brands to showcase their dolls, share the stories behind them, and connect with customers who value handcrafted products. Ramani Yellapantula, paper mache artist and Founder of Artefakt in Nagpur notes, “WhatsApp is my main platform and I mostly get orders here. Though we follow a word-of-mouth marketing strategy, our customers post their purchases on social media platforms and this helps spread the word, especially during festive season”. By sharing the stories of how their dolls are made, showcasing the cultural heritage embedded in each piece, and highlighting the artisans who create them, these small businesses can carve out a niche in a crowded market.

Konsam Ibomcha Singh holds workshops to teach school children the art of making Laiphadibi dolls

Konsam Ibomcha Singh holds workshops to teach school children the art of making Laiphadibi dolls

However, not all artisans are able to make this shift. While social media can be a powerful marketing tool, it requires time, effort, and digital skills—resources not all artisans have access to. Many older artisans find it difficult to navigate the world of algorithms and hashtags. Beyond digital marketing, the real issue remains the disparity between demand and supply.

Handmade dolls take time to produce, and artisans often lack the resources to meet growing demand. Singh explains, “Even though I can stir up demand for Laiphadibi dolls, supply becomes a huge issue because we don’t have enough artisans who are skilled enough to produce them.”

Sawantwadi’s Stick Figure dolls

Sawantwadi’s Stick Figure dolls

This is also where Barbie has the upper hand. Her mass production allows her to be sold at a fraction of the price of a handmade doll. And because Mattel can flood the market with Barbie dolls during the festive season, Indian artisans who rely on slow, traditional methods of doll making struggle to keep up. Even as initiatives like Make in India bring attention to locally crafted products, it’s an uphill battle for those working in the traditional doll-making industry.

The canny socio-entrepreneur could turn every bug of the Indian doll into a feature: The limited number of production could make them collectibles. Timing their launch with region-unique festivals, such as local harvests, solstices and important lunar dates would underscore their cultural significance. And accessories? Laiphadibi goes to Losar in neighbouring Arunachal, or accessories for Taka Taki’s first Gudi Padwa or Narayli Poornima. Who does bling and extra better than us? Their market would be the ever expanding Indian diaspora spread across the globe.

Yuvrani Shraddha Lakham Sawant Bhonsle of Sawantwadi

Yuvrani Shraddha Lakham Sawant Bhonsle of Sawantwadi

Many independent businesses are not only preserving traditional crafts but are also empowering local women. Yellapantula of Artefakt notes, “What makes Artefakt stand out is not just its focus on sustainability but its mission to uplift women by providing training and employment.” Pinklay follows the same ethos. “Pinklay dolls are more than just toys—they represent empowerment,” says Tanwani. “Made by women from underprivileged backgrounds—many of whom were unskilled workers—these women have been trained, continuously employed, and transformed through their work”. Thus each doll is a symbol of the woman’s journey to independence. How good this would look on a tag.

This model of empowerment through craftsmanship offers a powerful alternative to mass-production. These brands demonstrate that people over profit,

sustainability over speed, and culture over conformity are viable paths forward.

Artisans at work at Sawantwadi Palace’s Darbar Hall

Artisans at work at Sawantwadi Palace’s Darbar Hall

One of the greatest challenges facing traditional doll artisans is the lack of awareness about their craft. The current generation of children—and even many adults—are growing up without understanding the history and value embedded in these creations. “The younger generation is more interested in moving to cities for white-collar jobs,” says Singh. “They don’t see a future in this traditional craft, and that’s why there is a lack of artisans skilled in making Laiphadibi dolls.”

This is where education becomes crucial. Teaching children about the importance of local crafts can foster a deeper appreciation for them, not just as commodities, but as integral parts of cultural heritage. Workshops and school programs that allow children to experience doll-making firsthand could be transformative, sparking interest in learning these crafts. Parekh notes that, “For instance, after we conducted a workshop with Bombay International School (in Marine Lines), the children actually created their own dolls to represent textile and heritage.”

Avantika Bahuguna, Richa Singh and Mansi Zaveri

Avantika Bahuguna, Richa Singh and Mansi Zaveri

Singh also shares the importance of workshops for children. “I give training to interested youth about the craft, free of cost, and educate school children about this dying craft that has been in my family for generations,” says Singh.

Barbie isn’t going anywhere. That doesn’t mean India’s traditional dolls need to disappear. There’s room for both. As Mansi Zaveri, CEO of Kidsstoppress, explains, “Parents today are well-informed and becoming increasingly aware of the importance of supporting local artisans.” It’s not about choosing between Barbie and indie dolls. In the words of Tanwani, “India is evolving rapidly, and along with this growth, Made in India products are gaining well-deserved recognition and trust. We just hope that there is room for both local and global offerings, and that they can continue to coexist.”

Laiphadibi of Manipur

Lai translates to god in Manipuri, and phadi means a shabby piece of cloth. The last syllable, bi, denotes the feminine gender. So, laiphadibi is a feminine image of god, made from rags. Laiphadibi are considered living spirits that needed to be treated with respect. Ita Laiphadibee, is a popular Manipuri folktale. When the girl reached marriageable age, both were heartbroken. The laiphadibi granted her human a boon: To understand the language of animals. On her wedding night, the girl heard a fox talk about a corpse on the river with a magic ring on his finger. The girl decided to look for it, and her husband secretly followed. Watching her pry the ring off the corpse’s finger, the husband was convinced she was a witch and refused to take her back. The matter reached the king, and the girl laid out her defence, citing the fox. The king tested her by asking to translate what a crow was saying. She replied that there was treasure buried under the tree, which turned out to be true. The king married her, and the kingdom prospered under the new queen. The moral of the story is that laiphadibi, if treated with dignity, bring prosperity.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!