The third in a series that looks at who built Mumbai, reveals that shipbuilding and cotton mills developed the hinterland of the islands, where trade had only skimmed its shores

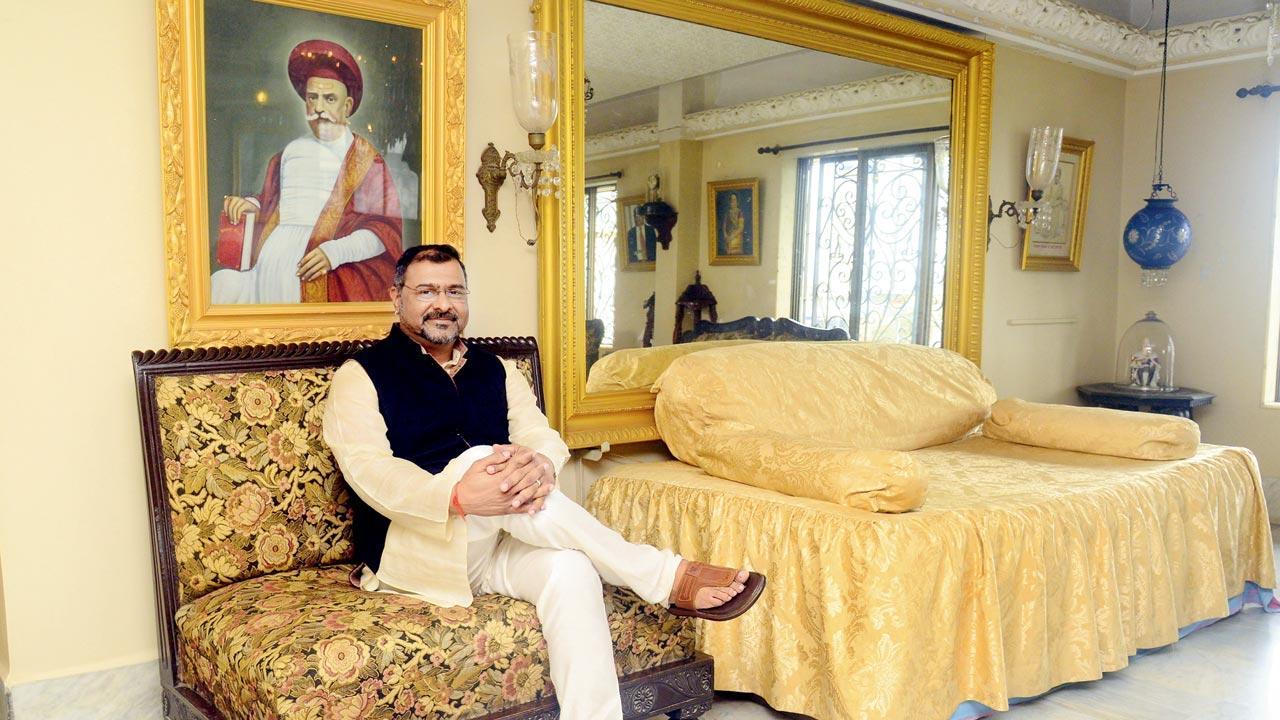

Amar Sunkersett, a sixth generation descendant of Jagannath ‘Nana’ Sunkersett, says his ancestor started the first school for girls in the western region. Pic/Shadab Khan

The Sunkersett bungalow, nestled in Girgaum, was more than a family home. In its backyard, bejewelled young girls in nauvari sarees, sat for lessons at a time when women were not allowed into schools. In one of the inner rooms, the first ever train ticket was issued by the Great Indian Peninsular Railway (GIPR)—from Bori Bunder to Thane.

By the time the most illustrious of the clan—Jugonnath Sunkersett Murkute (Jagannath Shankershett) aka Nana—helped shape the city, the family had been in Bombay for six generations and were financially comfortable enough to lend money to the British. Gunbow Street, which had the city’s first court, is the anglicization of his grandfather, Ganba Shett, after whom the street was named. The family had arrived from Murbad via Ghorbunder, now a part of Greater Bombay, as had many ‘sethia’ communities on the invitation of the English East India Company (EEIC) to conduct business in this new city they were building.

ADVERTISEMENT

In 1661, the seven islands of Bombay— Bombay, Mazagaon, Parel, Worli, Mahim, Little Colaba or the Old Woman’s Island, and Colaba—became part of Catherine of Braganza’s (daughter of Portugal’s King John IV) dowry when she married Charles II of England. The swampy islands were a political and financial liability by the Crown, and it leased it to the English East India Company (EEIC) in 1668 for an annual rent of £10 (marking the only time in the city’s history that rents were so low).

Mumbai was already a strategic transshipment and victualing port on the Indian Ocean trade routes, but “a strong navy [to safeguard against pirates], enterprising trading communities, an acquisition of a hinterland, all these are necessary ingredients for success,” writes community historian Sifra Lentin in her book Mercantile Bombay, which this writer relied heavily on for this article. Lentin is also a Fellow at Bombay History, a foreign policy think tank.

Senior journalist at mid-day, author and railways historian Rajendra Aklekar had reported in this newspaper about a proposal to rename Mumbai Central Station after Jagannath Sunkersett, who along with Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy, formed the Indian Railway Association, and helped create the Great Indian Peninsula Railway (predecessor to Central Railway with its headquarters at Boree Bunder, now CSMT). Pic/Getty Images

Senior journalist at mid-day, author and railways historian Rajendra Aklekar had reported in this newspaper about a proposal to rename Mumbai Central Station after Jagannath Sunkersett, who along with Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy, formed the Indian Railway Association, and helped create the Great Indian Peninsula Railway (predecessor to Central Railway with its headquarters at Boree Bunder, now CSMT). Pic/Getty Images

The EEIC provided all these ingredients. Unlike the Portuguese, they had zero interest in converting the locals, but maximum interest in building a bustling economic centre whose potential they had spotted as early as 1652, and written to Oliver Cromwell, then head of England. Surat, a riverine port on Tapi in Gujarat, was declining in importance as Mughal power shrunk after the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, and the Portuguese began controlling sea routes.

In 1687, EEIC shifted its naval base from Surat to Bombay, and with them came the many trader communities they were working with in Gujarat—the Parsis, Cheylias, Bohris, (Sindhi-Kutchi) Lohanas, Memons, and Patidars. Its sheltered open harbour could welcome larger ships, but needed a hinterland to store materials to be exported, and provide a market for imports. And so began the building of a city that would, for two centuries, be known as “the most important city east of Suez”. The Indian rupee became a multi-lateral currency travelling as far as East Africa and the Arabian states (‘baisa’ is the formal currency in some, and colloquial word for money in many of these states still). The GIPR even raised rupee-based stock in the London stock exchange.

Historian Sifra Lentin has traced the journey of trade in Bombay in her book Mercantile Bombay. Pic/Ashish Raje

Historian Sifra Lentin has traced the journey of trade in Bombay in her book Mercantile Bombay. Pic/Ashish Raje

The religious security Bombay offered drew out communities of the Konkan such as the Bene Israelis, Konkani Muslims and Hindus. It also became a refuge for those facing religious persecution in other countries—such as the Aga Khan from Iran, the Sassoons from Iraq and Armenian Christians from Turkey, Iran and Beirut. Most of these communities were already trading with or through Bombay and Surat from Basra and enroute to Cochin or Hong Kong.

The EEIC offered massive benefits to business communities, such as exemption from tax for the first five years, and by 1870, Bombay was a global hub for trade and finance. Its navy, which patrolled the western coast, is the forerunner to today’s Western Naval Command, headquartered in the city.

Shipbuilding at docks such as the one at Mazgaon, was the city’s first industry. Mazgaon Dock Limited recently underwent a R826-crore modernisation programme. Pic/Shadab Khan

Shipbuilding at docks such as the one at Mazgaon, was the city’s first industry. Mazgaon Dock Limited recently underwent a R826-crore modernisation programme. Pic/Shadab Khan

Ship-building became Bombay ‘s first large-scale manufacturing industry, and its pioneer was Lowjee Nusserwanjee Wadia. Already a reliable shipbuilder in Surat, Wadia was coaxed by the Company to come here in 1736. The city’s shipyards were already functioning, but Wadia established EEIC’s ship-building yard. In his life-time, Wadia built 57 ships and the trade continued down his family line; the Wadia teakwood ships became a gold standard after one of them endured nine ice-locked weeks in the Baltic Sea. America’s national anthem, was composed onboard a Wadia ship, the Minden. The oldest surviving Wadia ship, the Malabar teakwood warship HMS Trincomalee (1817-1986) is still seaworthy, and on display at the National Museum of the Royal Navy in England.

Soon, this city became an important port on the subcontinent transport of cotton, spices, teakwood, and pepper; but opium and cotton were the pillars of Indo-China trade. The famine in the south eastern provinces of China put a stop to cotton cultivation in these regions, and in 1730, raw cotton from Bombay made its way there.

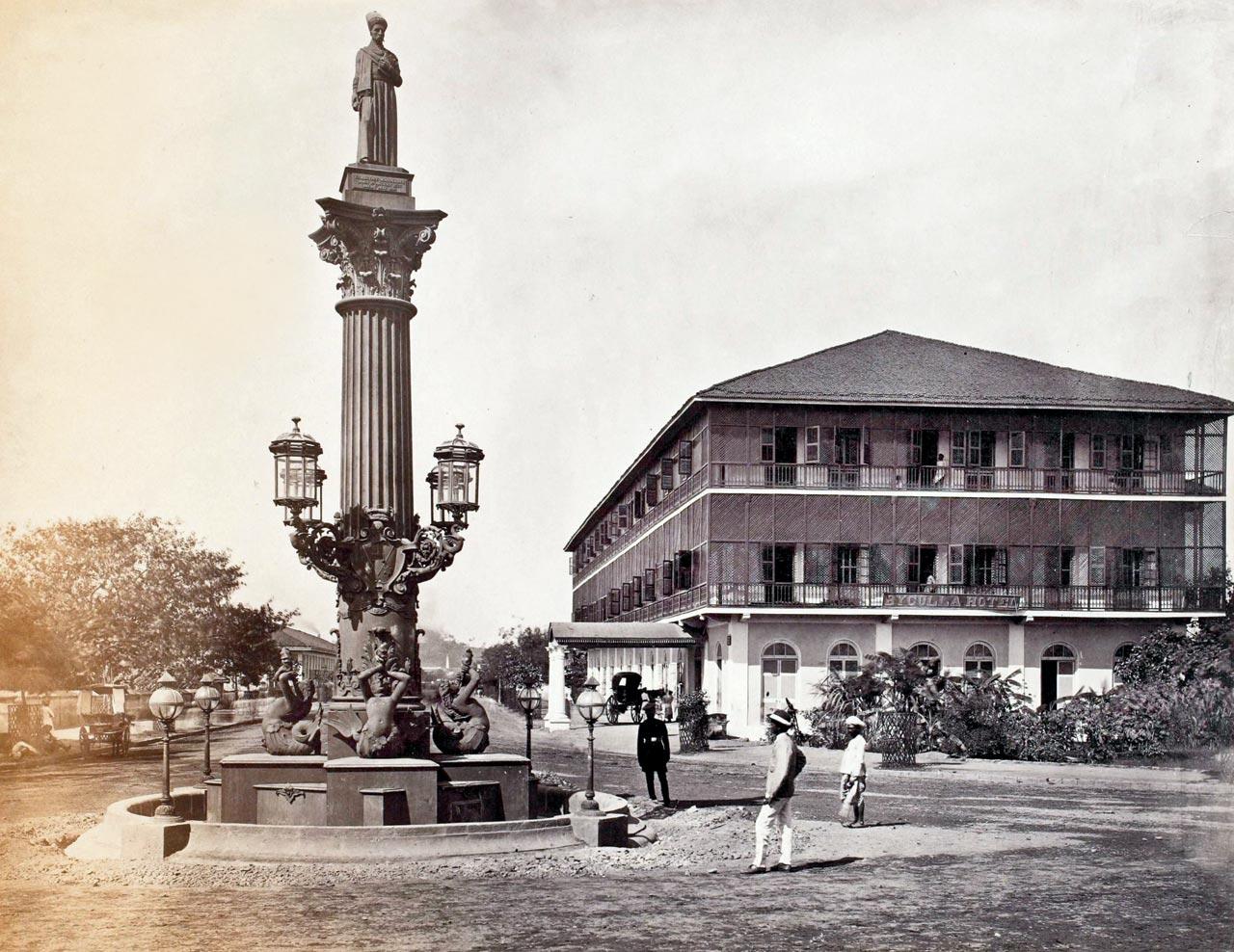

Parsi shipbuilder Lowjee Nusserwanjee Wadia was a pioneer of the industry in Bombay, after which several from his community shifted to the city from Gujarat. The Standing Parsi Statue and the Byculla Hotel, Bombay, c. 1850-1870, Francis Frith & Co.

Parsi shipbuilder Lowjee Nusserwanjee Wadia was a pioneer of the industry in Bombay, after which several from his community shifted to the city from Gujarat. The Standing Parsi Statue and the Byculla Hotel, Bombay, c. 1850-1870, Francis Frith & Co.

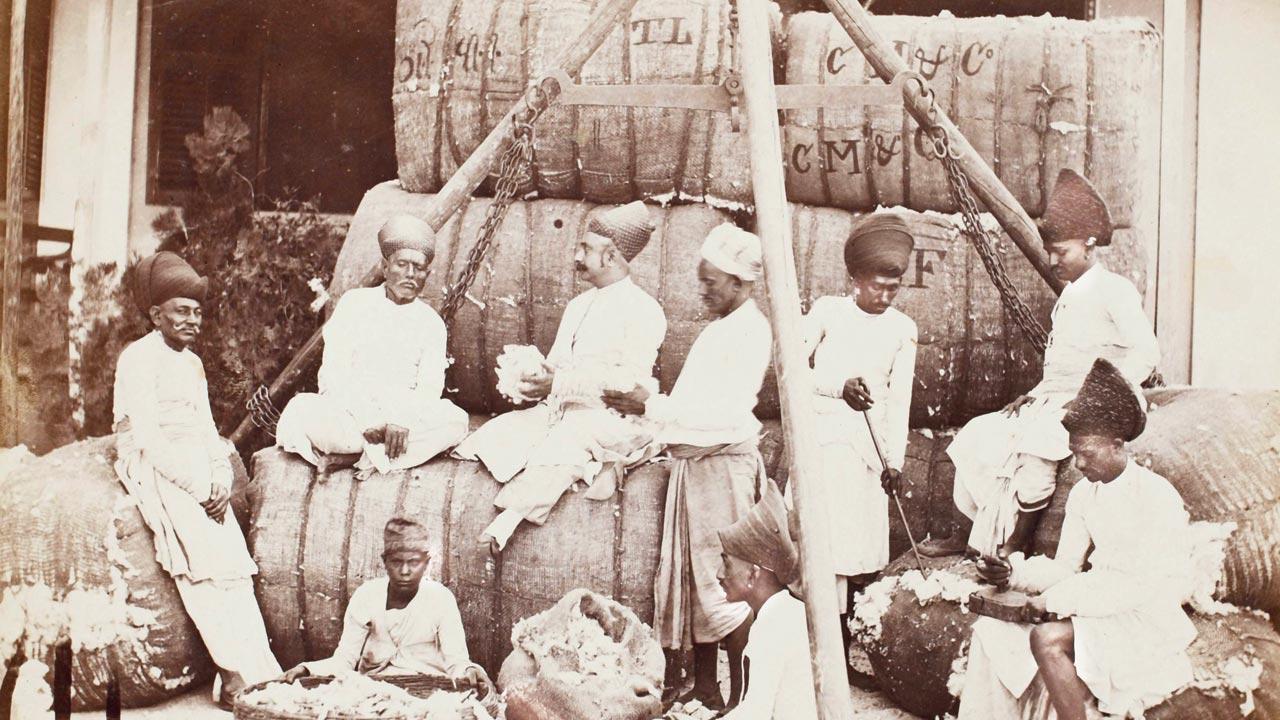

After shipbuilding, cotton trade catapulted the city into the spot of a global financial hub. Gujarat, the Deccan region and central India were already growing cotton, and the trading hub of Bombay was too close to ignore. The civil war in (the not yet United States) America also put a plug into the supply of the raw material from there to England. Cowasjee Nanabhoy Davar set up the first textile mill in 1851, and Maneckjee Nusserwanjee Petit followed in 1855. Within a decade, there were “10 mills of 25,000 spindles and 3,400 looms that consumed 40,000 bales of cotton annually,” writes Lentin in her book. As the 20th century came around, the Petits, the Elias David Sasson arm of the Sassoons, the Tatas and Sir Currimbhoy Ebrahim were the biggest mill owners.

Around this trade grew a network of Marwari sahukars, Gujarati money lenders, Bohris and the Khojas providing capital, raw materials, eateries and man power in the form of carpenters, saddlers, watchmakers, jewellers and tailors for uniforms. As sailors populated the areas around the docks, avenues of entertainment rose—brothels, pubs, gambling centres, shops and dance halls.

Cotton trade catapulted Bombay into the spot of a global financial hub. Cotton Merchants, Bombay, late 19th century, William Johnson and William Henderson. Pics/Sarmaya Arts Foundation

Cotton trade catapulted Bombay into the spot of a global financial hub. Cotton Merchants, Bombay, late 19th century, William Johnson and William Henderson. Pics/Sarmaya Arts Foundation

Families such as the Sassoon were already trading in spices and other goods, and when waters got too hot for Jews in Iraq, David Sassoon moved to Bombay. Unlike the Parsi merchants, Sassoon did not have an appetite for risk, and he and the Tatas rode only the second wave of the opium trade. Sir Jamshetjee Jeejeebhoy became one of Bombay’s richest sethias in the early half of the 19th century after he expanded his trade with China. With him came associates such as the Jain merchant Motichund Amichund, Konkani Muslim Mahomed Ali Rogay, and Goan Catholic Roger de Faria. Parsi traders had a stronger presence in Canton than any other Indian trading community.

Sassoon, who is said to have stitched Basra pearls into the lining of his coat as he fled, became a cultural and religious point person for Sephardic Jews. A visitor to his mansion in Byculla, now the Masina Hospital, would be assured of donation, grant or alms for a synagogue or Hebrew school; and they travelled from as far as Europe and the Arabian states, assured they would not go empty handed.

“Though the Sassoons,” says Lentin, “were certainly not the only Baghdadi Jews in the city, most of them in the mid 19th centuary were interrelated. By the time of his sons and grandsons, most Bombay Jews either worked in a Sassoon factory [his mills employed 15,000 workers]; or, if they were Baghdadi, were married into his enormous family of eight sons and five daughters [through two wives].” Trading in textiles, indigo, cotton, opium, and spices, he positioned his sons at vital centres such as London, Shanghai, and Hong Kong to leverage global colonial trading networks.

“India was the only country in their history, where the Jews did not face persecution,” says Lentin. “With Bombay’s growing economic prosperity, the marooned Jewish community of Bene Israelis came to the city to work as masons, carpenters and join native regiments of the EICC’s army”. Some Jews from Cochin, who had been trading in pepper for centuries, joined them.

“You could see that the Sassoons were very keen on giving back to the city,” says Lentin, “They built the Magen David synagogue in Byculla for the community to worship in, the Knesset Eliyahoo synagogue in Kala Ghoda, the Ohel David synagogue [where he is buried] and Sassoon hospital in Pune.” Then there are the Sassoon docks, the David Sassoon Library and Reading Room, the Bank of India, and the Sassoon building of the Elphinstone Technical Institute.By Independence, the Sassoons had wrapped up their India operations and moved to their other outposts—Hong Kong and Shanghai, and England.

On the other hand, son of the soil Sunkersett was low-key. Part of the Daivadnya Sonar community of Kokan region and from a family of once goldsmiths, Nana had expanded into real estate, exports, and money-lending (on the scale of a bank) to other businesses. “He was a visionary,” says Amar, a sixth generation descendant. “The Jagannath Sunkersett mulinchi shaala was the first school for girls in western India. He also contributed heavily to the girls school opened by The Students’ Literary and Scientific Society in Girgaon, now known as the Kamalabai High School in Thakurdwar.” He was also the first Indian member of the Asiatic society.

Homeschooled by tutors, Nana was passionate about education. “He established the Elphinstone College, which he named after his friend Lord Elphinstone, which was the first body of higher education to teach subjects in Marathi,” he says. “When he learnt that Indians were not going to medical colleges because they would have to bathe [as per religious sanctions] after touching a dead body, he established the Grant Medical College which included facilities for washing up. He was instrumental in setting up the Government Law College and Deccan College in Pune. He was also one of the donors for the JJ School of Art. But he gave none of them his name.”

The Sanskrut (spelt this way) scholarship in the Mumbai University is one of his enduring legacies, and is about a hundred years old. His family believes it might be the oldest one in the country. “At one point, people were not excited about who topped the matriculation exams; they wanted to know who got the Sanskrut scholarship,” says Amar, who lives in Nana Sunkersett Smruti apartments that sits on the street named after his ancestor in Chira Bazaar. Their home accommodates many of the artifacts, including chandeliers, from the Girgaum mansion.

Women’s emancipation being one of his fervent causes, he backed reformer Raja Rammohan Roy’s mission to abolish sati. “He was respected in the community, and though riots broke out in other cities over this reform, Bombay was calm owing, in most part, to his influence.” The Shankar-Bhavani temple (named after his parents) and the Ram temple at Nana Chowk are still owned by the family, though open to public, and adjoining housing societies (also named after Sunkersett) where most of the family lives.

As Bombay grew more multi-cultural, he donated large tracts of land (at one point, it was believed he owned half of Bombay), for crematoriums, Muslim and Christian burial grounds, and other places of religious importance. “A bade-sone-ki-chaddar is annually offered in the Muslim burial grounds at Charni Road to commemorate him,” says Amar.

Nana was also a visionary: He was instrumental in bringing the railways to India and was one of the two Indian directors on its board; the other being his friend Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy. “He was also on the board of the Steam Navigation company which formalised the shipping industry,” says Amar, “and the Bombay Gas Lighting Company which brought gas streetlights to the city, a first in the country.” Keeping a finger in each pie that bolstered the city, Nana was founder-director in 14 nationalised banks. “He also donated land for the first natyagruh [theatre] in Grant Road,” adds Amar, “and was instrumental in setting up Veermata Jijabai Udyan [Byculla zoo] and the now Bhau Daji laud museum. Several attempts to name endeavours after Sunkersett have been delayed or declined. Nana proved to be a lone stalwart from his family. His son, Vinayak Rao, had the potential to blaze his own path. However, he passed away in his mid 30s. There were several other multi-generational communities already living in Bombay, such as Afghan and Arab traders, as well as the Siddis brought as slaves by the Portuguese. The Afghan Pathans traded in saffron and dryfruit, which continues today. Eventually, the India-raised Pathan would play a starring role in what was to become the city’s largest industry—filmmaking.

A sizeable Japanese community (3,000 at the turn of the 20th century) re-located to Bombay as part of their work with Japanese trading firms. The 111-year-old Japanese Cemetary—Nipponjin Boji on Dr E Moses Road—is a remnant of the people who worked in the cotton industry and its trade. Then there is the Irani Shia community, most visible in some of the Irani cafes that still dot the city. They are said to have come 200 years ago, seeking better living conditions after a famine. The Dawoodi Bohra community already had a strong presence in Oman, east Africa and along the Strait of Hormuz before they moved to Bombay with their other Gujarati counterparts. The Bohra Bazaar Street and Bohra Masjid (now Badri Masjid) in Fort were already community hotspots by the early 1800s.

1730

Year in which raw cotton from Bombay made its way to China after a famine in the south eastern provinces put a stop to cotton cultivation in these regions

This article is part of Mid-day's Mumbai Konachi? series that looks at those who played a critical role in building Bombay.

Read earlier pieces from the series here:

Say hello to Bombay’s first citizens

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!