For queer content creators, trends like ‘Get Ready With Me’ are a way to experiment, be subversive, and find joy—amid the everyday cruelty of trolls

Suraj Namboodiri is fighting stereotypes about gay men and masculinity offline and on social media. Pic/Anurag Ahire

Not too long ago, Suraj Namboodiri was a muscular, masc-presenting man. The solitude of the early lockdown months, and the slowing down of life, meant that he was on his own, living every day without any judgement from co-workers or strangers. A health setback prevented him from working out, but it commanded the kind of rest that he needed to introspect. It also allowed him to experiment with how he wanted to present himself, embracing another important part of his identity and living a fuller life. In 2020, at 26, Namboodiri came out as a gay man.

ADVERTISEMENT

As he proudly dabbles in makeup and fashion while building his body back, the Goregaon-based fitness coach is fighting stereotypes about gay men and masculinity in real life—and on social media. Singing along to a popular Kareena Kapoor Khan song, Namboodiri wears understated, sparkling golden eye shadow and a shimmering green kurta in an Instagram Reel made specially for Diwali. He may act coy in the video, but even Namboodiri acknowledges that it is one of his most successful—garnering 127k views.

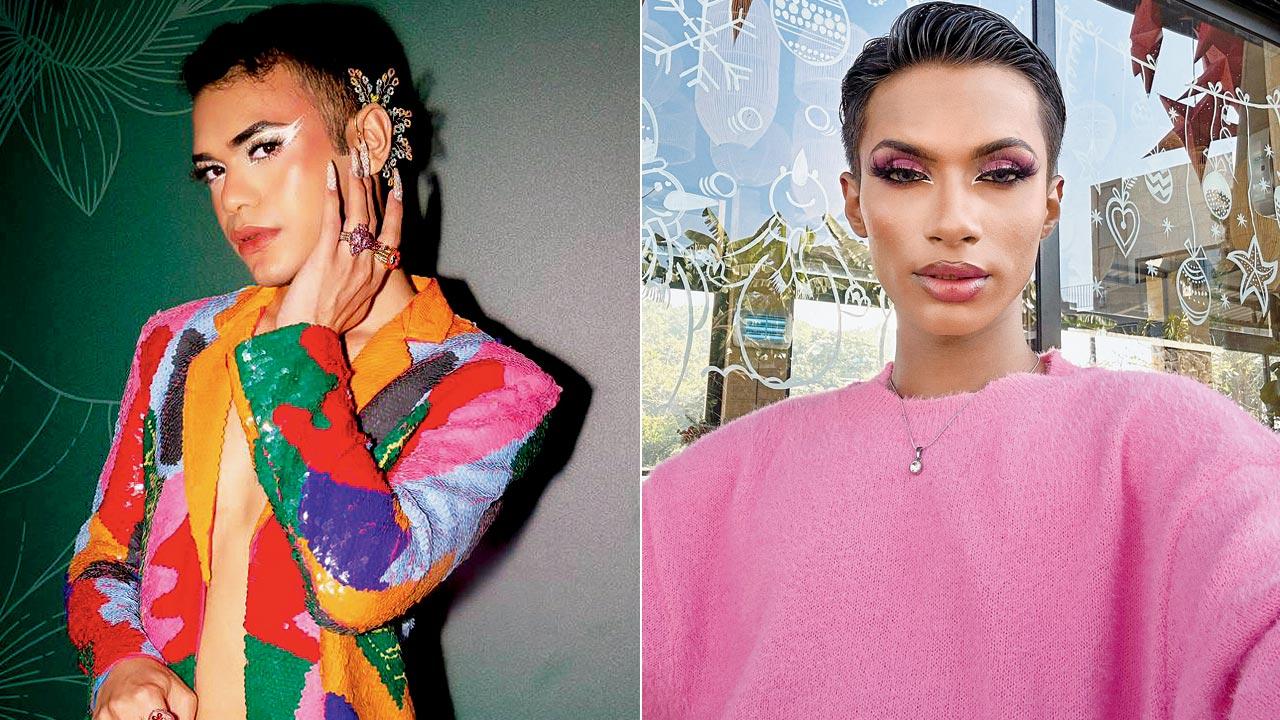

“Creating Get Ready With Me videos allows me to assert my identity and expression,” says Deep Pathare; (right) Rahil Sayed disregards negativity, choosing instead to focus on the positive impact their content has

“Creating Get Ready With Me videos allows me to assert my identity and expression,” says Deep Pathare; (right) Rahil Sayed disregards negativity, choosing instead to focus on the positive impact their content has

“I personally love ‘Get Ready With Me’ videos, he says, “but I know that much of the reach of my Diwali Reel and the comments under it are from trolls. Their tone was quite like that of toxic comments under Pranshu’s Diwali video. People kept describing me as a man transforming into a woman, and predicted that I too would succumb to trolling,” Namboodiri says, reflecting on the dangerous reality of being a visible queer creator in India.

His voice turns sombre each time he speaks of Pranshu, a 16-year-old queer creator from Ujjain who reportedly died by suicide on November 21. In their journey

towards becoming a makeup artist, Pranshu ran an extremely popular Instagram account covering beauty, skincare and fashion. Like Namboodiri, they too posted a reel for Diwali—where they wore an elegantly draped saree. In the aftermath of their death, Pranshu’s mother Preeti Yadav drew attention to the hate comments and negativity that they were subjected to.

Fatiha Tayyeba: makeup artist; Gargi Ranade: counselling psychologist; Jeet: co-founder of Yes We Exist; Ruchita: MH clinician

Fatiha Tayyeba: makeup artist; Gargi Ranade: counselling psychologist; Jeet: co-founder of Yes We Exist; Ruchita: MH clinician

Pranshu’s case is representative of the treatment meted out to many queer creators, especially those whose content is focused on makeup and fashion. His death has stirred the LGBTQiA+ community, sparking conversation about the mental health of young queer persons, as well as the inability of social media platforms to safeguard their users from waves of bullying. Through conversations with queer creators in urban India, mid-day finds out what content creation means to them—as a site of performance, identity assertion and exploration—even in the face of harassment.

Gurgaon-based Ashrey Puri reminisces about drawing and painting as a child. Three years ago, during the COVID-19 pandemic, he began experimenting with the Euphoria makeup trend that was popular on social media. What he didn’t see coming was the overwhelmingly positive response from his followers, motivating him to make more content. “It all began on that one night where I sat with my mother’s makeup and uploaded a video the next day… After my first video, I ordered two palettes—it was a big step for me to buy my own makeup because I never foresaw that I would get into this profession, even though I enjoyed watching tutorials on YouTube,” the 22-year-old says.

For Ashrey Puri, buying makeup for the very first time was a big step—for his career and identity. Pic/Nishad Alam

For Ashrey Puri, buying makeup for the very first time was a big step—for his career and identity. Pic/Nishad Alam

Puri is now a full-time makeup artist and content creator who collaborates with brands. He asserts that his audience, though niche, understands his essence. “I’m someone who loves being extra; ‘no-makeup’ makeup looks are not for me! I think my audience recognises this about me, and likes it too,” he says. Puri adds that he feels lucky because his family has supported his career choice, and his content has found acceptance—a privilege that not all queer creators enjoy. To him, makeup is more than just an art form. “When I was a kid, I could not do this. It validates my inner child.”

Established creators like Rahil Sayed and Deep Pathare, who have 45.6K and 25.5K followers respectively, say that content creation has been a transformative, affirming experience. “Creating Get Ready With Me videos is a celebration of queerness, allowing me to assert my identity and expression within the queer spectrum. The content I produce becomes a means to explore and showcase how and who I am. This experimentation brings a sense of joy not just to me, but all queer creators,” says Pathare.

This sense of queer joy is also true in Sayed’s case, who says that even when they are not defining what is in vogue, they can be a trend-setter just by being themselves. “As someone with dark skin, I felt a responsibility to represent my community authentically and challenge stereotypes about ‘Indian’ skin. Simply put, I do what I love,” Sayed says.

Jeet, co-founder of Yes We Exist, a forum that advocates for queer rights and highlights issues faced by the community, says that online platforms are essential for queer individuals and the expression of their gender identity because doing so in their real lives “invites trouble, from affecting their personal safety to being denied housing and jobs. For young queer people who are at a crucial point in their lives, such as when they are transitioning, sharing their real life journey online frequently leads to greater levels of cyber bullying.”

Often, the larger audience response to trans women who elegantly drape sarees—especially on festive occasions—is not a recognition of their fashion chops. It is a discriminatory, reductive response to their gender and a perceived mismatch in the clothing they “ought” to wear. Makeup artist Fatiha Tayyeba says the question of conformity and nonconformity defines how queer creators are perceived by larger society. In her experience, Tayyeba found that established artists and influencers tend to do what is already done and accepted. “Being experimental is a step towards fighting against conformity and established norms in beauty—this includes gender stereotypes. Sadly, it will take time for people to see makeup as an art form and mode of self-expression,” the makeup artist says.

Puri tries to see negative comments as an increase in engagement, sometimes responding to trolls with sass, but not at the cost of his mental health. “If it begins to affect me, I’ll switch the Comments feature off. That being said, I see how 4,000+ hate comments on one post can get to someone. The comments on Pranshu’s video were unimaginably hateful and mean. Trolls have persisted in their comments even after his death. It’s inhuman,” Puri rues.

Namboodiri has observed that queer creators’ work is derogatorily employed in the material put out by many in the fitness industry who have rigid ideas of masculinity. “I personally know of people whose videos have been used to troll and make fun of people who don’t work out, or work out differently using support,” he says.

On most days, he isn’t too affected by targeted hate because he believes he is experimenting with makeup and fashion, first and foremost, for himself. “After having been bullied since I was young and learning to develop strong resolve, at 29, I no longer feel afraid,” he says. On some days, though, Namboodiri has contemplated quitting social media. When he began posting content, he was picked by Snapchat to be a queer creator—a selection that felt, at first, like an hour. But the demands from the platform about videos and numbers, coupled with the overwhelming hate, bogged him down. “People who hide behind fake or anonymous accounts which cannot be traced, say these vile and dark things because they think there will be no consequences,” he says.

Sayed and Pathare prioritise their mental health during challenging times, just as Puri advocates. This perspective allows Pathare to decide when they should call out a troll or ignore them entirely. “When faced with negativity, I adopt different strategies depending on the situation… My advice to fellow queer creators is to prioritise self-care, surround yourself with a strong support system,” the 26-year-old beauty and skincare creator says. Sayed sees negative response as a glass-half-full phenomenon. “I choose to disregard negativity, believing that one should focus on the positive.”

Though multidisciplinary artist and activist Roshini Kumar doesn’t hesitate while posting on Instagram, they do feel scared for others who are queer, especially for younger creators—in the aftermath of Pranshu’s death. “It’s incredible to see young people embrace their queerness and gain confidence—with the support of their families. I wish I could have done that, at their age. Unfortunately, it is these young people who have to be careful about their online existence because trolls are not held accountable at all; they go to frightening lengths and have no remorse,” Kumar says.

A strong and consistent risk factor—is how counselling psychologist Namrata Khetan describes online bullying and its impact on queer youth, who face this issue at a greater rate than their cis-heterosexual peers. “The constant exposure to derogatory comments and trolls creates an environment filled with anxiety, depression, and paranoia. Persistent online hate can erode self-esteem,” the Mumbai-based practitioner says. “The stress from online hate can manifest physically through sleep disturbance, headaches and poor eating habits.”

Reflecting on queer people’s life-long struggles, mental health clinician Ruchita Chandrashekar reminds us that they are subjected to dismissal and discrimination in their immediate environments. What sets online trolling apart is the sheer numbers. “It’s never one person. It is usually a mob saying the vilest things. This can worsen existing emotional wounds and create newer ones,” Chandrashekar says.

Many queer people under the age of 25 have been social media users since their pre-teen and teenage years, practically growing up on these platforms; their early embrace of online identities is a double-edged sword. “An important part of personality and psychosocial development occurs between 13-21. Identity, sense of self, role of community and role in the community are taking shape in these years so this age group is extremely vulnerable and understandably much more sensitive,” Chandrashekar explains.

The consequences of online trolling palpably spill over into an individual’s offline life, says Bengaluru-based queer counselling psychologist Gargi Ranade, as they internalise hate—beginning to hate their own queerness—and question their identity and authenticity. “It may discourage them from coming out to people in their real lives.

Receiving hate can alienate and isolate people from others, even those who might be able to support them through this,” she explains.

Central to the conversation about these creators and queerphobic hate is the very idea of social media and how “safe” it is. Khetan points out that online harassment leads to a fear of visibility, making queer youth reluctant to express their identity openly, instead hiding their authentic selves. Yes We Exist’s Jeet says that many queer creators cannot opt to shut their Comments off, make their accounts Private or deactivate their social media accounts because their professional work is inextricably tied to them. Taking these actions directly affects the creators’ reach and engagement, further affecting the opportunities they have access to in the future. One of the forum’s focus areas instead is shifting the conversation to make social media platforms more accountable. “There’s very little awareness on how to protect yourself online; ideally, this is a subject that the government and schools should tackle, given the number of young people who are affected. And the platforms themselves are to blame: There is insignificant investment by Meta to create awareness about their features which can be used to reduce abuse. If you aren’t fluent in English, it becomes more difficult to fully harness these features,” he says, adding that many queer users have ceased to report hateful comments because Instagram cannot recognise queerphobic slurs in regional languages that violate Meta’s community standards.

“Even if the hate isn’t directly targeted at me, it does affect us all. Instagram allows trolls to operate with impunity, making them unafraid of perpetuating hate—the sort that calls for violence and celebrates death,” Jeet explains.

Ultimately, Ranade says, the lack of safety means that queer existence online is often a trade-off. “You can have a private account with a select few people as your audience [which can also validate your queerness], or you have a public account and endure hate comments. Creating safe spaces online takes an immense amount of mindful effort and that can be quite taxing,” she says.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!