A new cookbook traces the roots and evolution of the Nair Onam sadhya from rural, traditional tharavad homes to modern, urban restaurants

The author writes about science and Ayurveda being involved in the sadhya which is a balance of six tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, pungent and astringent, and a melody of textures, from crisp to soft to watery; In Kerala, the operations of catering companies have replaced the large scale home cooking once conducted in tharavad houses on Onam. To prepare sadhyas-in-a-box, caterers convert large grounds into kitchens where sorting, cleaning, cutting and cooking are done on an industrial scale and completed dishes are packed on an assembly line. Each box serves four to six people and banana leaves are delivered along with the boxes. Frozen, vacuum-packed sadhya containers in boxes are also shipped to various parts of the world.

Around this time last year, chef Arun Kumar TR was in Kerala “looking for the Onam of [his] childhood”. On the day of the festival, his driver—a Mappila Muslim—had wanted to go home for a sadhya he would be eating with his family. A sadhya, Kumar had been surprised to learn, that would consist not of Mappila dishes but of traditional vegetarian items served on a banana leaf. “That showed me that the festival had penetrated different quarters and was now celebrated by all.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Originally a religious festival focused on the celebration of Vishnu, Onam underwent a gradual secularisation beginning in the decades when the movement for uniting Malayalam-speaking regions into Kerala gathered momentum. In the 1960s, when the communist government declared Onam a state festival encompassing all people, the legend of the asura king Mahabali became popular and Vishnu receded to the background.

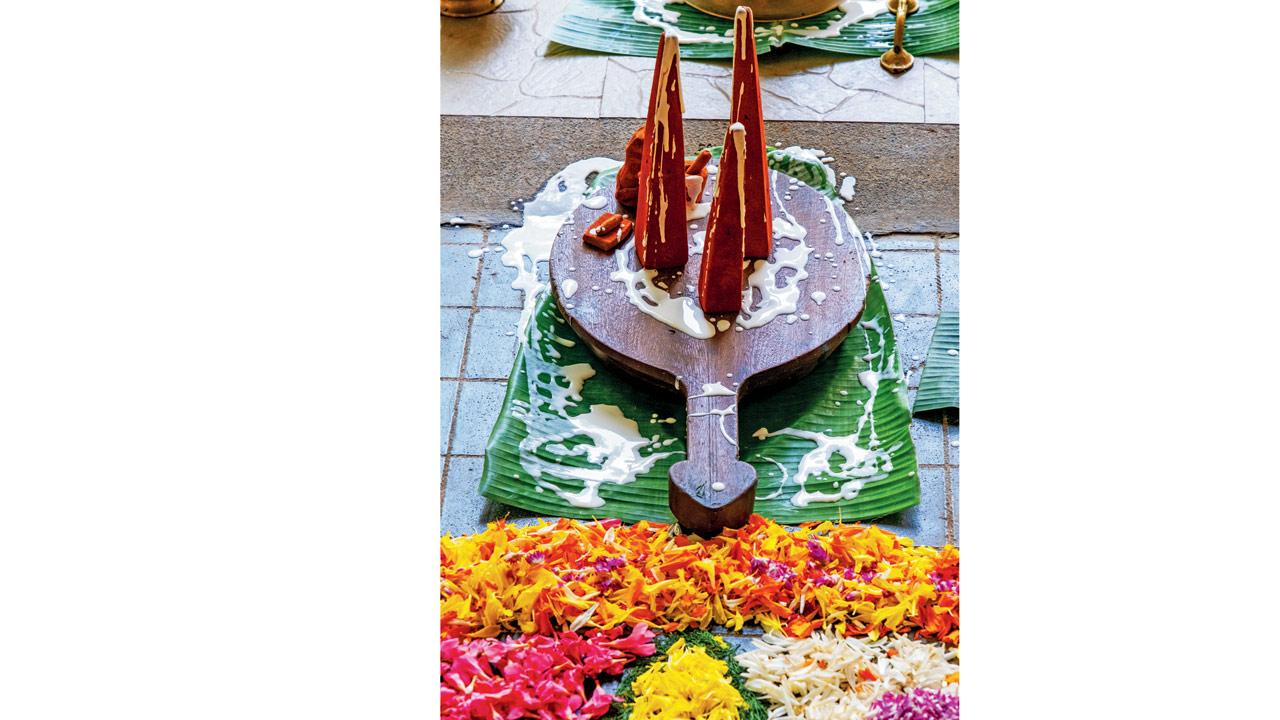

Onathappan or Madhera sprinkled with rice flour in water. The pyramid-shaped clay figurine is a traditional idol associated with Onam and once represented Lord Vishnu but is now associated with the demon king Mahabali and his return from the netherworld during the festival to visit his people

In his book Feast on a Leaf: The Onam Sadhya Cookbook (Bloomsbury India), Kumar writes about the ubiquity of Mahabali during the festival: “Today, when you go to Kerala during Onam, you see Mahabali everywhere: On posters announcing a sale, as a cutout at the entrance to a shop; and as men dressed like him greeting patrons at malls, hotels and restaurants. Interestingly, the umbrella carried by the Vamana avatar [of Vishnu] has passed on to Mahabali.”

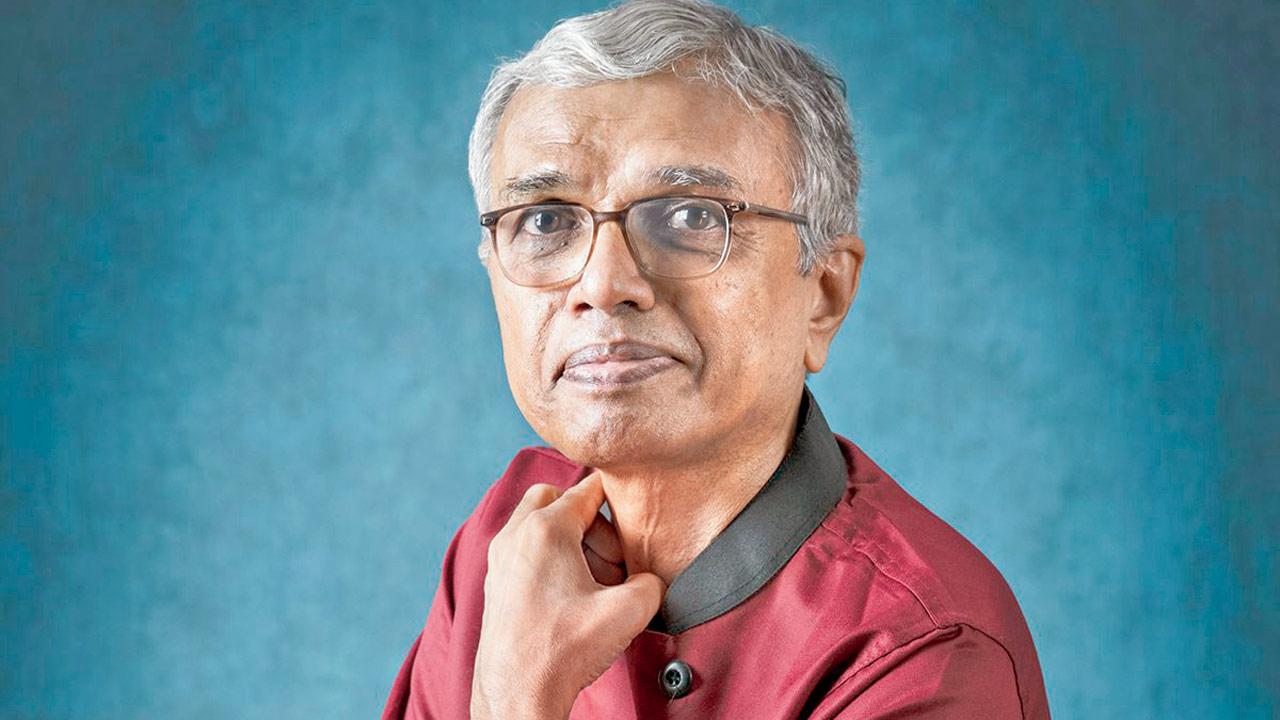

Kumar, once a journalist and filmmaker, has been working as a full-time chef for 10 years and says that his spirit of inquiry (“there’s no such thing as an original recipe”) and man management skills are learnings from his previous vocations that help him as a chef. He has cooked and supervised Onam sadhya festivals at restaurants, and says that he learned during interactions with people that what incites fascination about a dish is the story that it can be traced back to.

Hailing from a Nair family, Kumar has witnessed sadhyas being cooked at his parents’ ancestral homes, or tharavads, in Kerala. It is the stories and memories of these grand home-cooked communal feasts and of an integrated form of community living where what was on the plate came from “the tharavad backyard” that frame his recipes of accompaniments, curries, thorans, payasams and desserts that make up the iconic Malayali meal at the centre of his new cookbook.

Along with popular folk-art forms such as Theyyam, Kathakali and Pulikali, the Chundan Vallam or snake boat races form an important part of celebrations in Kerala. These long and narrow boats, can extend up to a hundred feet in length and are manned by a large crew. PICS COURTESY/BLOOMSBURY INDIA

Kumar reminisces about the practices of the tharavad home: The rituals of forging Onathappans (pyramids) out of red clay and assembling vibrant pookolams (flower carpets); the traditional kitchens with wood-fired stoves or adupus, utensils such as urulis (shallow, circular, bronze vessels), meen chattis (fish-shaped, curved cutting boards) and ammi kals (grinding stones); the procuring of vegetables and fruits like jackfruits and bananas from gardens or orchards, and the use of natural materials such as wood, bamboo and palm leaves for storage.

However, Feast on a Leaf is also about the transposing, as it were, of the large Onam sadhya from “very well-designed, efficient and tightly run tharavad kitchens which procured, stored and used ingredients optimally and in a very systematic manner” to “equally well-designed and efficient modern kitchens”, all the while promoting a farm-to-leaf approach with locally-sourced seasonal produce, minimal processing and little wastage.

Kumar offers a peek into how at restaurants, he attempted through mock drills rehearsing the ritual meal’s complex serving—from the placement of leaves such that the tail end is on the left of the person, and the handling of chomukhas or serving vessels with four containers, to the wearing of mundus and perfecting the order of serving the 24-plus dishes—to replicate the fluidity of the meals.

The book acknowledges that as families have scattered, many tharavads now only have elderly residents or have been converted into homestays and museums. “The tharavad kitchen during Onam is a totally different ballgame when compared to restaurants. The tharavad way of cooking the sadhya is perhaps lost,” admits Kumar. “But I wouldn’t lament it,” he is quick to add.

Arun Kumar TR

Equipment such as electrical stone grinders, he explains, are making processes easier, while retaining old textures and flavours. “Instead of trying to replicate things exactly, the focus should be on continuance of ingredients, textures and flavours. There is science and Ayurveda involved in the sadhya which has a balance of tastes and it is important to preserve that,” he notes.

There are people now who use carrots and peas in the avial. He once found gobi Manchurian at a sadhya. “These are things I’m completely against. I think the sadhya—the way it was and the way it can be made—has a certain value to it.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!