As deepfakes proliferate the digital space, going beyond revenge porn and political propaganda to find use in the corporate space, experts reflect on their impact, need and potential

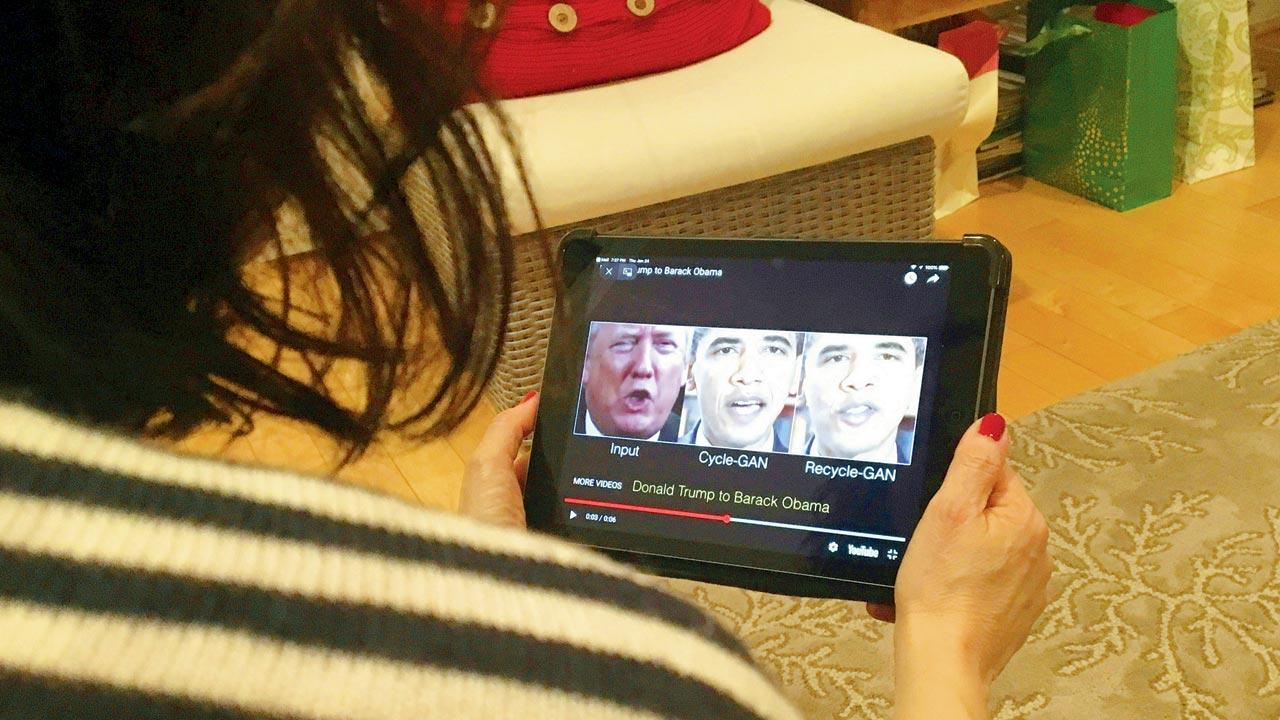

A woman in Washington, DC, views a manipulated video that changes what was said by former presidents Donald Trump and Barack Obama, illustrating how deepfake technology can deceive viewers. Pic/Getty Images

Last year, soon after Queen Elizabeth II delivered her annual Christmas Day speech, a digitally-created fake of the Queen, aired on Channel 4, danced across TV screens and, warned viewers to question “whether what we see and hear is always as it seems”. The video, the broadcaster said, was created as a stark warning about the advanced technology that was enabling the proliferation of misinformation and fake news in a digital age. Again, earlier this year, 10 videos posted between February and June on TikTok, showed actor Tom Cruise doing coin tricks and biting into lollipops among other things. The videos, unsurprisingly, drew millions of views. But they were not of the Hollywood A-lister. They were in fact, created by visual and AI effects artist Chris Umé with the help of a Tom Cruise stand-in. The videos’ popularity inspired Umé to launch the company Metaphysic, which uses the same deepfake technology to make ads and restore old film.

ADVERTISEMENT

These of course, are examples of advanced deepfakes—the term combining the words “deep learning” and “fake”—created by professionals with the help of voice actors in what is a complicated and expensive process. While the use of such high-quality deepfakes may not pose a widespread threat just yet, as Vladislav Tushkanov, senior data scientist at cybersecurity company Kaspersky tells us, the technology might be used for phishing attacks. Citing an example of the uses his organisation has been tracking for some time, he mentions a recent attack on a company in Great Britain where an executive was phished to transact money to perpetrators when they used a deepfake technology to mimic the voice of one of the officers of the company. “We also saw some deepfake-based phishing videos where an individual claims to be someone else, using the face of a person who is kind of famous to scam people to go on specific websites, pay money, etc.”

A video of the famous Mere Saamne Wali Khidki Me song from the ’60s comedy Padosan went viral a few months ago with the faces of cricketers MS Dhoni and Virat Kohli, and actress Anushka Sharma replacing those of its original cast

Along with the rampant use of celebrities’ faces in porn and the even more concerning spread of malicious revenge porn, political deepfakes—such as the suspicious video of President Ali Bongo of Gabon used by his government to mask speculations around his health or those that surfaced of MP Manoj Tiwari a day ahead of the Legislative Assembly elections in Delhi last year to reach out to voters of different linguistic groups—have for some time now raised alarm. This is for their potential to influence people with disinformation, and rattle their faith in the media they consume.

“It’s not just one technology,” says Tushkanov, pointing out that deepfakes combine different tools that enable face swapping, lip syncing, voice generation, all of which are evolving at a fast pace right now. “In my opinion, the most efficient thing that companies and governments can do is to educate people. If people are not checking facts and just relying on the information they get from social media, chats and messengers, they will fall for it…” But deepfakes, he believes, are not the only things to blame, pointing to a more pernicious media and cultural landscape. “It’s not like it is this technology per say that is dangerous. Even in the absence of this technology, people can spread false information. This is just one way to do that.”

A deepfake of Queen Elizabeth II aired on Channel 4 last year, warning viewers to question “whether what we see and hear is always as it seems”

Closer home, a video of the famous Mere Saamne Wali Khidki Me song from the ’60s comedy Padosan went viral a few months ago with the faces of cricketers MS Dhoni and Virat Kohli, and actress Anushka Sharma replacing those of its original cast. “Quite a few features on Instagram and TikTok too use deepfake, but in a more obvious way, where you can transpose your face onto that of a rabbit or dog,” points out Karthik Srinivasan, a communications professional. “Those also use similar technology but they make it very explicit. It is not intended to deceive, but to entertain,” he says, adding that within the world of entertainment, the technology has perhaps had its most exciting uses. Actor Bruce Willis, he cites, recently licensed his deepfake for use in some Russian cellphone ads, while a promotional campaign for the Hugh Jackman-starring film Reminiscence allowed people to upload photos to animate as teasers, so they could see themselves featuring alongside Jackman. Also, realisable, is the possibility, he says, of making stars of yesteryears who have passed on act alongside current ones. “That would be interesting and something that’s bound to happen.”

Vladislav Tushkanov and Karthik Srinivasan

A Wired article recently reported how accounting giant EY has of late started the use of deepfakes, calling them ARIs (standing for artificial reality identity), in client communications where virtual doubles of their partners made with AI software are used in video clips to accompany presentations and emails. The technology appears to now find use as traditional ways of forging business relationships decline. UK startup Synthesia, an AI video generation platform, which instead of filming video content with a camera, uses AI software to simulate real videos, has facilitated this. Its cloning process requires the subject to sit before a camera and read a special script, providing the company’s algorithms with examples of the person’s facial movements to be able to mimic their appearance and voice. It even provided a translation function that allowed an EY partner with no knowledge of Japanese to get his AI double to speak Japanese for a client.

“The interesting thing is that they clearly mention that it is not the employee, but a digital replica of the employee that is doing the talking. So, it is completely above board and honest,” says Srinivasan, adding that their novelty rests in the fact that they seem to possess a personalised quality. “Imagine the response to a [customer’s] query coming from the CEO’s face… It seems more personal, although it’s actually just faking the personalised quality.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!