The script for Mumbai’s most loved small-format newspaper was written by two journalist friends during a chance conversation over dinner. In his just-released memoir, Khalid A-H Ansari reveals how he made Mid-Day possible with “nothing except fond hope”

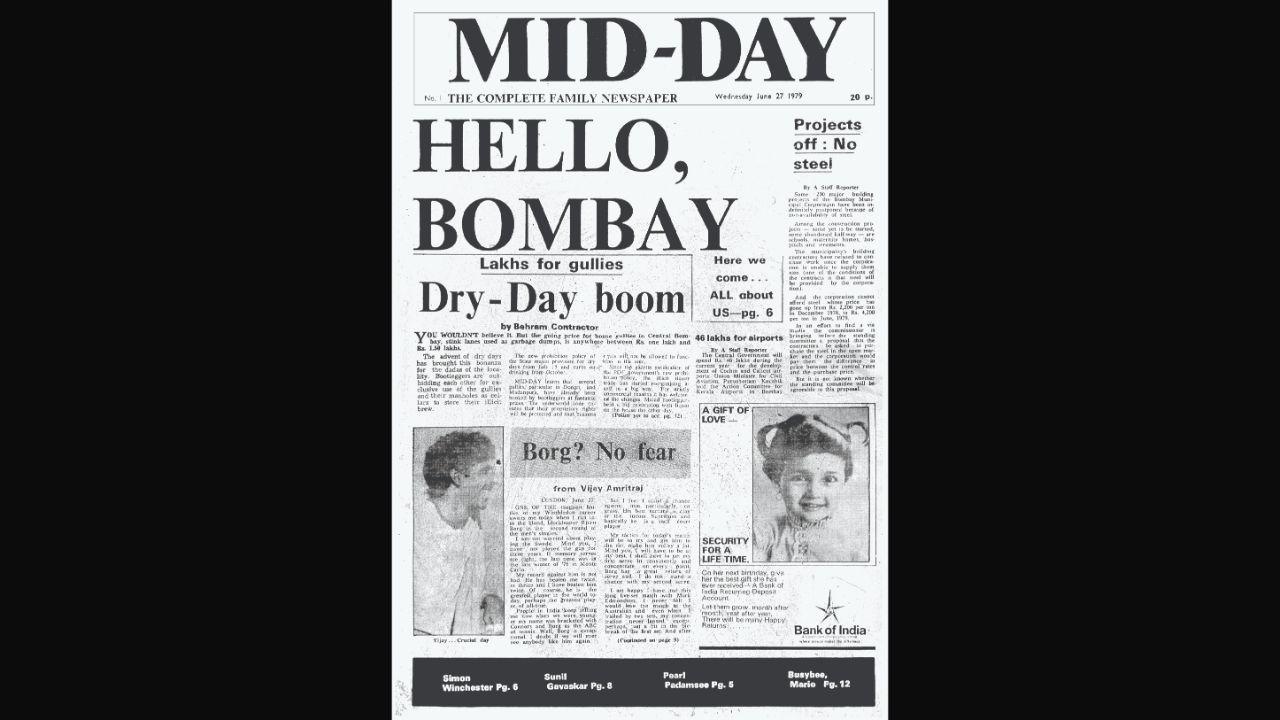

The first issue of Mid-Day, dated June 27, 1979

IN A rare kind of reception, world cricket’s best-known personalities open the pages of a just-released memoir. These blurbs, or appreciations—as titled in the book—enumerate qualities reserved only for brilliance. And yet, Khalid A-H Ansari, the man being discussed, uses self-deprecation to shield himself from this praise. “Jab upar wala meherbaan toh gadha pehelwaan [When God smiles kindly, the donkey thinks he’s a wrestler],” writes Ansari, as he leads us into his extraordinary journey in It’s A Wonderful Life: A Memoir (Rupa Publications).

ADVERTISEMENT

He was born in Mumbai’s working class mill workers neighbourhood Madanpura, which along with neighbouring Bhendi Bazaar in the 1930s was home to some of Mumbai’s Urdu literary greats like Kaifi Azmi and Kamal Amrohi.

Ansari’s father Abdul Hamid Nizamuddin, journalist, educationist and freedom fighter, was the founder-editor of Inquilab (The Revolution). Eighty-three years later, the newspaper continues to be India’s most widely read Urdu daily. With 14 editions, it is owned along with Mid-Day by Jagran Prakashan Limited.

Ansari fought the disillusionment of growing up in a home with five half-siblings and a step-mother who made “life hell for me,” with his pen. The St Mary’s School and St Xavier’s College alumnus, went on to secure a scholarship at Stanford University, California, only to return to start one of India’s leading sports magazine, Sportsweek. During his illustrious journalistic career, Ansari remained committed to sports, especially cricket, which as Rahul Dravid puts it, “he was a great supporter of”.

With Field Marshal SHFJ Manekshaw and athletics coach Jal Pardiwala (centre) at an All India Council of Sport event. Khalid A-H Ansari had shared the first copy of Mid-Day with Field Marshal Manekshaw, during an event at the Taj Mahal Hotel Ballroom at which the latter was the chief guest. PICS COURTESY/ It’s A Wonderful Life: A Memoir (Rupa Publications), Khalid A-H Ansari

And then, he went on to establish the newspaper brand you hold in your hand—Mid-Day—in June 1979, retiring as its founder-chairman 33 years later in 2012.

At the time of his retirement, Ansari, who is a recipient of the Padma Shri (2001), was also the chairman of MC Media Ltd, whose activities included FM Radio broadcasting—a joint venture with the BBC, London—in eight Indian cities. His memoir paints a vivid portrait of a life lived close to the field, and off it. In this excerpt, he tells the extraordinary founding story of Mid-Day.

Edited excerpts from the book

IN hindsight, the decision to start an afternoon paper was another exemplification of the allegory about the donkey thinking he’s a wrestler. In the early ’70s, the unassuming Behram Contractor was fast becoming a legend of sorts among readers of Mumbai’s afternoon newspaper, the Evening News of India of the Times of India group because of his sharp wit and formulaic name-dropping of the city’s haute monde.

I recall a chance meeting with Behram at a press conference. We soon struck a warm friendship to the extent that I would be invited to all his parties and vice versa. And he would mention me in his column to an embarrassing degree. On such an occasion, many hours into the night, I was invited to a dinner at his Churchgate flat and, as was our normal practice at each other’s home, stayed back after all guests had departed, solving the world’s problems, as we would jokingly term it.

Many hours into the night I realized Behram’s light in the balcony facing the railway station was on. I mentioned this to Behram who went ‘blink-blink’ (as was his distinctive peculiarity), stepped out and returned to inform me that it wasn’t his balcony light but the sun that was rising. Such was our enjoyment of each other’s company.

In fact, even after Behram left Mid-Day to branch out on his own and start the rival Afternoon Despatch and Courier, we resumed this practice at his Harkness Road flat without objection from his indulgent wife Farzana. At one such dinner at my home for some international cricketers at which Farokh Engineer, Imran Khan and Rohan Kanhai were present, Behram stayed back after my wife Rukya had gone to bed. For some reason our conversation veered to his job at the Evening News of India.

Since we were now close friends, I thought nothing of asking Behram if he was happy with his job to which he replied categorically: ‘If you start a daily newspaper, I’ll chuck up my present job and join you tomorrow,’ in a manner that reminded me of Aziz Currimbhoy and Sportsweek [the magazine which Ansari launched in 1968]. We both laughed it off and Behram made his way home.

Ruminating over the previous evening’s conversation over my morning cup of tea the next day, an epiphany of sorts struck, I picked up the phone and invited Behram to lunch to ask if he was serious about what he had said the previous evening. To my astonishment he, stone-cold sober, confirmed that he had. And thereby hangs a tale!

To be absolutely honest, I was shocked out of my wits. Although I had long nursed the desire to start a daily newspaper, it had always been a fond hope—and nothing else—for the simple reason that I just didn’t possess or have access to any resources worth talking about. My father had repeatedly warned me about the perils of partnership.

After Mid-Day had established itself, I was privileged to be invited by the likes of the feisty Ramnath Goenka, owner of the multiple-edition Indian Express, the self-made Dhirubhai Ambani whose spectacular rise from humble beginnings as a mere clerk in Aden, Yemen, to the richest man in India is the stuff of legend.

Also, by SP and Gopichand Hinduja of the multifaceted Hinduja empire and Vijay Mallya, the high-flying entrepreneur who later in life ran afoul of the law—for discussions over lunch or tea, which were inevitably infructuous because of my father’s conviction about partnerships.

In my moments of idle conjecture, I sometimes wonder what might have been had I decided to merge my family’s humble publishing endeavours with any of those giants, only to realize that that is a futile exercise. Nor did I have a proper roof over my head: no office premises, printing capacity beyond what was required for the Inquilab, human resource, admin, marketing, production personnel, editorial staff versed in the English language, stock of newsprint worth talking about, nothing; nothing except fond hope on a wing and a prayer!

Even dreaming of starting an English newspaper under the circumstances was imbecility of the most egregious sort. It must be said to Behram’s credit that he took my casual suggestion seriously, promptly speaking to many of his colleagues, as also friends and acquaintances in the profession and managing to rally the troops, in a manner of speaking.

Malavika Sangghvi, who put her hand up when Behram mooted the idea to her, recalls: “Behram had NO idea about Khalid Ansari’s financial resources nor his management expertise—all he knew was that ‘he was a nice young man with a pleasant personality.’”

In an interview to Society, Behram Contractor said: “In January 1979 the blueprint for Mid-Day was prepared, in March we had set a date for kick off [27 June]... Four of my colleagues and myself resigned from our jobs at The Times of India and consequently lost our leave and other allowances for not giving adequate notice.”

In its issue of 12–25 July 1979, Businessworld wrote: If an enthusiastic staff was Ansari’s greatest asset, Mid-Day’s working environment and infrastructure were far from satisfactory. It also quoted me as saying, I was a little mad, to put it mildly, to attempt to bring out a daily newspaper and weekly magazine (Sportsweek) on our eight-year-old antiquated Newsking two-unit web offset equipment, and there were several breakdowns. And to add to the frustration of periodic machine breakdowns, Ron Hendricks, the deputy editor, left after two months because he reportedly could not see eye to eye with Behram Contractor. But despite these setbacks, within six months Mid-Day had managed to break even and, since its launch, doubled its price from the initial 20 paise to 40 paise and revised its advertising rates from R6 per column centimetre (contract) and R8 (casual) to R26 and R29 respectively.

Behram said the following about his initial thoughts on the publication:

“Brought up as I was—journalistically speaking—in a somewhat uppity newspaper atmosphere, Sunday Mid-Day’s curious product mix of some well-known and not-so-well know names in different spheres was a little difficult for me to stomach in the beginning. Yet, despite my scepticism the formula proved to be right, as was evident from the sales in the market.”

The article went on: “Spurred by its success, the Mid-Day team embarked upon their next venture—Sunday Mid-Day, a weekly that claims to give ‘value for money’with regular columns on investments, astrology, homeopathy, a beauty guide and even a true confessions column. Since its launch, Sunday Mid-Day’s sales graph has moved in one direction—upwards. On 13th July 1980 when it hit the newsstand 50,000 copies of the Sunday paper were printed of which 40,000 copies were sold. Since then, despite revising its prices from 40 paise to 60 paise in a year, Sunday Mid-Day commands a circulation of 84,000 and a Thursday ‘dak’ (early) edition of 20,000 which is sent to the country’s major metropolitan cities.

What accounts for the spectacular success of Mid-Day and its Sunday edition? ‘Readability and objective reporting,’ says Contractor. ‘We don’t believe in fighting for causes or carrying out campaigns on our pages. We report the news and let the reader judge for himself. We also believe in pictorial stories and therefore have three fulltime photographers on our staff.’

Not that it has been smooth sailing all the way. Until 1979 Sportsweek and Mid-Day were being printed on machinery that even Ansari admits is obsolescent. ‘The tension was too much,’ reminisces Ansari. ‘when the machines broke down, which they did frequently, the printing was held up and timeliness is very important in this business. Even today, colour pages have to be farmed out and until we acquired our own phototypesetting machines in 1980, typesetting had to be done elsewhere. It required enormous patience and coordination to make sure everything went right. In late 1979, we acquired one Orient Press unit manufactured indigenously and another one of the same brand last month. And although this has helped our printing capacity, lack of infrastructure

has hampered our growth considerably.’

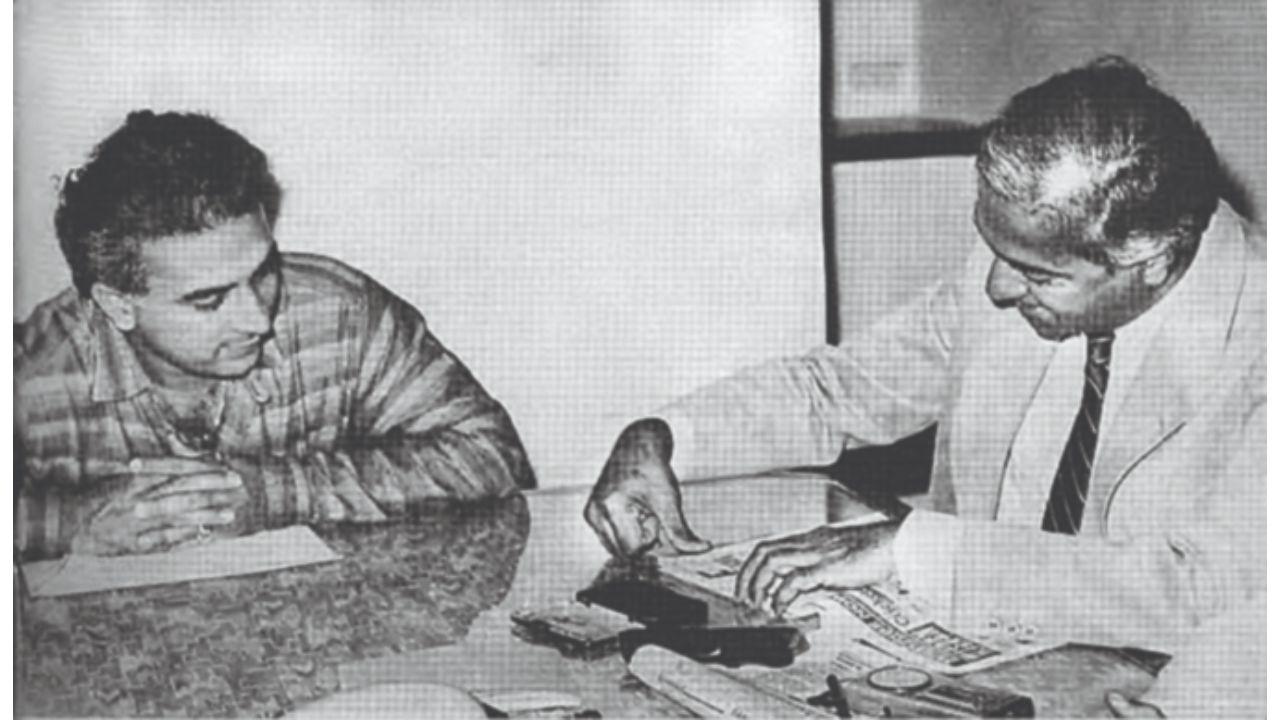

In a lighter mood with Sunil Gavaskar, while giving his thumb impression after signing him on as editor of Sportsweek in 1988

The working conditions too are far from perfect, though Mid- Day’s staff which brought out the first edition of the paper despite a leaking roof and puddles, bravely soldier on with promises of a brand new Nariman Point office on the horizon (Incidentally, we did move our Ad Sales department to Nariman Point a few years later.)

But whatever other problems that he may have been confronted with, recurrent labour agitation as is the norm in the newspaper industry, has not been one of Ansari’s major headaches. Not that Ansari has not had his share of troubles. In July 1979 for the first time ever in the history of the company, six members of the Inquilab staff struck work for a week demanding a revision of pay scales.

Recently, on Mid-Day’s second anniversary, except for the editorial teams, all production personnel of Inquilab, Mid-Day and Sportsweek struck work for a day.

‘Though slightly taken aback by the first ever labour agitation on our hands, we managed to devise a wage policy that was acceptable to both sides and within a week all employees were back at work,’ says Ansari who is however reluctant to comment on the reasons that prompted Inquilab and Mid-Day publication employees to resort to strike action. ‘Negotiations for demands such as sickness leave, etc. are still going on,’ admits Ansari.

With the Indian hockey Olympic team at the Ansari home prior to their departure for the 1978 Buenos Aires World Cup: Ashok Kumar (extreme left), Behram Contractor (second from left), hockey legend RS Gentle (third from left), editor of Sportsweek Sharad Kotnis (fourth from right), assistant editor of Sportsweek Gopi Baskaran (third from right), future sports editor of The Times of India Sunder Rajan (second from right) and racing correspondent of The Times of India Cecil Hendricks (extreme right). Daughter Tehzeeb and son Tarique seated on floor

His trials and tribulations notwithstanding, Ansari has a number of new projects up his sleeve. Already working on the launch of an edition of Mid-Day from Bangalore and Delhi, the journalistic grapevine is humming with rumours of Ansari’s attempts to acquire Bombay’s ailing morning daily—the Free Press Journal (circulation: 40,000).

‘My dream is to start a morning daily,’ says Ansari enigmatically and adds, ‘I hope to retire at the age of 50 and do something quite different—farming for instance.’

With seven years to go, the chances are that the man who has surprised the press barons with his smooth entry into the big league of Indian journalism may do it again—launch a successful morning daily before he makes for the green fields.”

• • •

Among some superstitious people in India, there is a belief that rain on an important occasion can portend either extreme calamity or unmitigated good luck! Be that as it may, in the case of Mid-Day, it rained torrentially from the previous night, right through the day and into the next night.

On the morning of the launch, to the flash of lightning and clap of thunder, we made our way to our office/printing press premises at a low-lying Tardeo junction, which is prone to knee-deep flooding, to be greeted by the heart-breaking sight of our drenched newsprint rolls, stacked in the passageway for lack of indoor space. The makeshift ceiling below the porous roof of the leaking, dilapidated super-structure was drip, drip, dripping as editorial and other staff took their seats above their typewriters, umbrellas in hand.

If all that wasn’t bad enough: the antiquated studio and pre-press departments were ankle-deep in water with staff valiantly trying to drain the water out. At around press-time (11.30 am), the electric supply failed and came back only at around 1 pm when word came in that the obsolescent printing press was refusing to respond to the print foreman’s commands.

The edition had been “put to bed” according to schedule at 12 noon, but there was no sign of the press starting. Precious minutes turned to agonizing hours and the hawkers, in anticipation of the new paper, touted as ‘bright, new, exciting’ were getting resigned to seeing a stillborn.

With witless optimism—and bravado, as I see it in hindsight—I had decided to be installed the same day as president of the Rotary Club of Bombay Mid-Town at 7 pm at the Taj Mahal Hotel Ballroom at which Field Marshal Manekshaw had very kindly agreed to be chief guest. Apologizing profusely to my staff at a hurriedly called meeting, I rushed off home at 4 pm—egg all over my face—to try and look respectable, and unfazed, for the inaugural function. I had left word at the press for the first copy of the newspaper to be rushed to the function in a sealed envelope for my eyes only.

With tennis ace Leander Paes, winner of 18 doubles Grand Slam titles, men’s singles semi-finalist at the Atlanta Olympics in 1996 and one of the greatest doubles players in tennis history

With one eye at the entrance, I was getting increasingly apprehensive as the function got under way with no envelope in sight at 8.30 pm. Imagine my mixed emotions when the envelope was finally at hand. I slipped it under the head table at which we were seated, sneaked a surreptitious look at the contents to ensure it wasn’t blank or totally black and, hands trembling, handed the copy to the field marshal.

‘Here we are, sir—my first copy of Mid-Day.’

The field marshal, unmindful of the large audience, unfolded the copy, looked at his watch, then at me, smiled and said with an expression that I can only describe as one expressing beatitude, ‘Call it bloody “Midnight,” Khalid.’

Excerpted with permission from It’s A Wonderful World: A Memoir by Khalid A-H Ansari, published by Rupa Publications

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!