The recent attempt to stifle fact-checker Mohammed Zubair is just another tactic from a tried-and-tested rulebook on extra-constitutional censure, which experts feel is jeopardising freedom guaranteed by a democracy

Alt News co-founder Mohammad Zubair seen leaving from Tihar Jail after being granted interim bail by the Supreme Court, in New Delhi, on July 20. Zubair was arrested by the Delhi Police on June 27 for allegedly hurting religious sentiments through his tweets. Pic/PTI

While the journalist fraternity, human rights organisations, and political Opposition have not stopped cheering since fact-checker Mohammed Zubair was granted bail by the Supreme Court this week, the incident has once again put the spotlight on extra-constitutional censure in the country.

ADVERTISEMENT

In Zubair’s case, the apex court not only offered him protection in all the seven cases foisted against him, but also transferred all his cases to Delhi from Uttar Pradesh, rejecting the UP government’s request that Zubair be “stopped from putting out tweets”.

Though India has had a long and ugly tradition of extra-constitutional censure by both state and non-state actors, Zubair’s legal counsel, advocate Vrinda Grover feels his case stands out not only because of who he is, but because of what he does. “Information and misinformation today travel at lightning speed, and various agendas and propaganda depend on this continuous generation and consumption of information. This is why a ‘fact checker’ becomes so essential to the flow of information in a modern democracy,” she says, adding, “Zubair, and others, including journalists, play the critical role of alerting citizens to fake news, false propaganda, which regrettably is often deployed to mislead public discourse, and manipulate public opinion. To incarcerate Zubair is not just to gag one man’s voice, but to silence democracy.”

A file photograph of a protester blackening a mask of writer Salman Rushdie, condemning his stay in Mumbai, in January 2004. Rushdie was alleged to have made remarks against Prophet Mohammed in The Satanic Verses. Pic/Getty Images

South Mumbai social historian-activist and veteran journalist Abde Mannan Yusuf traces how “this Frankenstein” was permitted to flourish since Independence, “producing haloed holy cows by our legislatures, law enforcement organisations, and even the thinking populace”. “As a result, attacks on freedom of expression became increasingly direct, brazen, and in your face,” the septuagenarian says.

He laments: “For a country positioning itself as a superpower awaiting rightful position at the international high table, such boorish stone age stances can only attract sniggers from the international community.” Yusuf cites UN chief Antonio Guterres’ spokesperson Stéphane Dujarric’s reaction, who recently while responding to a specific question on Zubair’s arrest at her daily news briefing in the United States, had said: “... Journalists should not be jailed for what they write, what they tweet, and what they say. And that goes for anywhere in the world, including in this room.”

Yusuf admits feeling let down when otherwise verbose powers-that-be quietly consent to such lawlessness. “[In Zubair’s case] This is a brazen witch hunt emboldened by the current political climate. Every time groups/individuals got away with earlier misdemeanour’s they upped their viciousness in the next attack. That is what has brought us to this juncture. We must choose whether we want to be remembered for the Mars expedition, proudly featured on our new R2,000 note or for incarcerating free thought, stirring up communal tensions and polarising to win elections.”

Protesters burn an effigy of Nupur Sharma during a demonstration in West Bengal demanding the BJP leader’s arrest. Pic/Getty Images

Grover underlines the role of a complicit police force and lower judiciary in helping facilitate an ecosystem for extra-constitutional censure. “The police force has regrettably almost always taken the cue from its political masters, and this has only intensified over the last few years, targeting independent-minded dissenting citizens, thus jeopardising personal liberties,” she says, while pointing out why the role of the lower judiciary becomes extremely crucial. In our legal scheme, the Magistrate is the first line of defence of civil liberties, and the Code of Criminal Procedure entrusts the Magistrate’s court the authority to determine the fate of a person’s liberty, guaranteed under Article 21. “Unfortunately, the pattern we have been seeing for some time now is that lower courts routinely remand arrested persons into custody, without any incisive scrutiny of allegations. The law requires the Magistrate to form an opinion [on whether] the allegations are ‘well-founded,’ before proceeding to assess if there is any need/desirability to remand an accused to custody. But, the entire exercise has almost turned into a formality, and this allows the police to get a free pass in cases of motivated arrests.”

According to Yusuf, the template that is being adopted by all and sundry today has its roots in newly Independent India. Back in 1947, Indian poet Majrooh Sultanpuri was imprisoned in Arthur Road Jail by the then-Bombay Presidency’s CM Morarji Desai for writing a poem, where he referred to Jawaharlal Nehru as “a lackey of the Commonwealth”. “Sultanpuri was instructed by Desai to recant and apologise, but the poet chose to accept a two-year prison term instead,” says Yusuf.

Journalist and BJP spokesperson Prem Shukla says the noose tightened further during Nehru’s first tenure as PM. “Both Madras Chronicle whose Marxist editorial policy was critical of Nehru’s economics and Organiser which targeted Nehru for his politics of minority appeasement faced censure. The very first amendment to the Constitution (19a) was brought about because of that,” says Shukla.

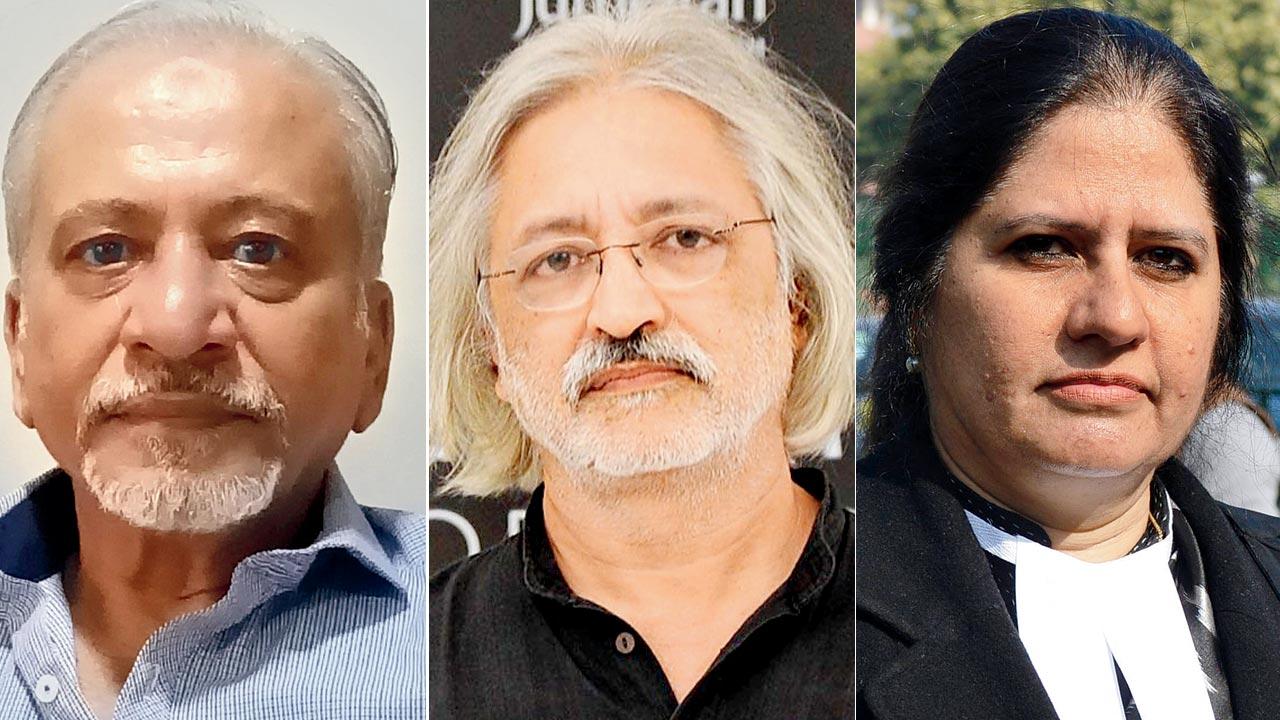

Abde Mannan Yusuf, social historian, activist and veteran journalist; Anand Patwardhan, filmmaker; Vrinda Grover

Back in the day, several authors also discovered their works outlawed—officially and even, clandestinely. The Ramayana (1954), a parody by the Indo-Irish Aubrey Menen, was forbidden as the content had been deemed inappropriate in certain places.

Late novelist-playwright Kiran Nagarkar’s Bedtime Stories (1978), where the Pandavas and the Kauravas are contrasted, had it worse. “I was unable to stage any performances. The censor board in Maharashtra requested an astounding 78 cuts!” Nagarkar had chuckled, while talking to this writer barely a month before his demise. By the time theatre professionals, critics, and academics forced the government to change its mind, the Shiv Sena had already spotted a soft target and a chance to use its trademark disruption to drive away actors. This saw Bedtime Stories subject to an extra-constitutional prohibition for 17 long years.

The venerable playwright Vijay Tendulkar also experienced the wrath of such prohibitions for his renowned Ghashiram Kotwal, an allegory of Shiv Sena’s politics, as well as his biting indictment of marriage and caste in Sakharam Binder.

Playwright Pradeep Dalvi had to knock on the court’s doors to ensure that his play, Mee Nathuram Godse Boltoy, ran without any disruption. “Both sides used my play to grind their political axes. During shows, audiences screamed slogans and vile abuse against Gandhi. It came to a point when some anti-Gandhi groups only came to disrupt the play. They would clap and whistle during the scene where Gandhi is shot. It got so repulsive I had to go to court,” late Dalvi had told this writer in an earlier interview.

Salman Rushdie’s The Moor’s Last Sigh, where a character named Raman Fielding resembled Sena supremo Bal Thackeray, and Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie, which India banned after Singapore, were other victims of authoritarian overreach—even after the government’s subsequent informal ban was overturned by the Supreme Court, bookshops in Maharashtra refused to stock Rushide out of fear of vandals from the Sena.

Several writings of exiled Bangladeshi author Taslima Nasrin have also been outlawed in West Bengal. Ram Swarup’s book Understanding Islam Through Hadis was outlawed “for inciting communal strife”. American historian James Laine’s Shivaji: Hindu King in Islamic India and translation of the 300-year-old poetry Sivabharata (The Epic of Shivaji) also suffered a similar fate.

It’s too recent to forget how India drove out her own Picasso, Maqbool Fida Husain, for his work, which some far-right groups found offensive. Husain who was forced to obtain Qatari citizenship, died broken-hearted in London in 2011. Artist Anjolie Ela Menon, who was a close friend of the painter, has expressed regret about how Husain was treated. “His critics never did comprehend him or his work to begin with. Tragically, certain would-be writers and performers collaborated with fringe organisations to continuously attack him and compel him to flee the country.”

In 1975, Gulzar’s political drama Aandhi came in the line of fire. The film was outlawed by the Indira Gandhi-led Congress government as the lead actress’ character was allegedly modelled on the PM. Aandhi wasn’t released until 1977, when the Janata Party took office. The same administration also outlawed the political satire Kissa Kursi Ka (1977), which dealt with the Emergency. The Shah Commission that investigated the excesses of the Emergency, found Sanjay Gandhi and the then-I&B minister VC Shukla guilty of destroying the film’s prints. Shukla incidentally forbade Kishore Kumar songs from playing on All India Radio after the singer declined to perform at an Indira Gandhi rally.

This became a norm with movies. Shiv Sena coerced director Mani Ratnam into altering how Shiv Sena leader Bal Thackeray was portrayed in Bombay, which was set against the 1992-93 riots. Be it Fanaa (banned in Gujarat as Aamir Khan supported Narmada Bachao movement), Ae Dil Hai Mushkil (Raj Thackeray’s MNS issued an ultimatum for casting Pakistani actor Fawad Khan), or the Tamil Mersal (which the BJP objected to because lead actor Vijay made fun of the new tax system and the Digital India initiative), films have become the easiest targets today.

Documentary filmmaker Anand Patwardhan of Bombay: Our City, Father, Son; Holy War, War and Peace; and Jai Bhim Comrade fame, says the state now outsources censorship to non-state actors. “All the state needs to do is facilitate a socio-legal ecosystem, which lets the lumpen on the street go out and do its dirty work without fear of being hauled or getting away with nothing more than symbolic action. The current dispensation even rewards them with seats in Parliament. A signal is being sent out that targeting Muslims is okay. Unlike Dalits whose votes they need, they have chosen to completely leave out Muslims even while deciding candidates.”

While commiserating with Zubair, Patwardhan says, “There are several like Siddique Kappan, Teesta Setalvad, Sanjiv Bhat and others being held captive by the vindictive government.”

He seems to echo essayist and Booker Prize winner Arundhati Roy, who has previously said she sees “no end to the conflicts in India that result from the country’s taboos which can lead to the lynching, shooting, burning, and mass murder of fellow humans.”

BJP’s Prem Shukla pins the blame on “selective outrage”. He cites the Nupur Sharma case. “Tasleem Rahmani, Chairman of the Muslim Political Council of India, provoked Nupur by first saying offensive things about Hindu Gods. Though the BJP, which the Opposition likes to call anti-Muslim, is in power, why is there not a single case anywhere against him?”

TJ Joseph, lecturer at the Mahatma Gandhi University-affiliated Newman College, Thodupuzha, whose hand was amputated at the wrist back in 2014, due to blasphemy allegations made by members of the Popular Front of India, feels there should be no tolerance for extra-constitutional punishment. “No one should have to go through what I went through, that too for a non-issue. I hadn’t made fun of the Prophet. While the 13 accused got away with minor charges, I lost my hand, my job, my family suffered and we were made to feel like pariahs.”

Didn’t the founding mothers and fathers of this land foresee a time when all four arms of the government would fail and large swathes of mainstream media would become their cheerleaders? Grover smiles and quotes Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar: “However good a Constitution may be, if those implementing it are not good, it will prove to be bad. However bad a Constitution may be, if those implementing it are good, it will prove to be good.”

According to her, the founders who shaped the Constitution drafted a charter of rights and freedoms for persons and citizens and arranged the division of powers between different organs. “The Constitution is a dynamic document and new and varied freedoms and rights have been conceptualised and affirmed over the decades, as citizens have asserted diverse causes before courts and Parliament.”

Shukla feels that popular blogging/microblogging sites have now taken articulation of opinion out of the hands of a select few. “This throws up several challenges and we will have to find a way of working around those.”

Grover, however, warns that there are still many socially, economically, and politically marginalised groups and discriminated communities, that the present model of governance keeps impoverished. “This systemic and crippling injustice needs redressal. Activist citizens and human rights defenders play a central role in countering this injustice and discrimination. Not surprisingly they are increasingly targeted by the state.”

She laments that the state’s chosen weapon is now the law, which carries not just a sheen of legality, but an inherent legitimacy. “The criminal law machinery has been weaponised to incarcerate and silence activists, dissenting, courageous, and assertive citizens. What is of grave concern and very disturbing to see is that the court at times views this activist citizen with suspicion, rather than follow the dictum of the Constitution which through the preambular goals and Chapter III, places limits, checks and curbs on the powers of the state.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!