The lure of Lamington Road goes beyond being Bombay’s IT haven and cinema paradiso

Dilip Shah at Solar Tyres, which was set up by his father Balkrishna in 1953 at 1910-built Tottie Terrace. Pic/Bipin Kokate

Dilip Shah at Solar Tyres, which was set up by his father Balkrishna in 1953 at 1910-built Tottie Terrace. Pic/Bipin Kokate

ADVERTISEMENT

Every street is special. What makes some more so, I ask myself, gingerly padding a dug-for-the-Metro pavement on Lamington Road. Delicious diversity does. Having recently scanned Maharashtrian and Gujarati cityscapes, I'm stirred straight into a mixed grill here, Parsis, Iranis, Muslims, Christians and Anglo-Indians adding strong flavours to savour.

While Anglos from Edwards and Whartons to McCarthys and Majors emigrated, the rest pack the sprawling path named for Charles Cochrane-Baillie, 2nd Baron Lamington, Governor of Bombay from 1903-07. For sure, this central stretch bursts with charisma vaulting miles beyond acknowledged sweeps of IT hub, cinema circuit and auto haven.

Spectacularly wide to scope in a page and a half, I sample the street in pockets. Like Lamington Cross Road - or Alibhoy Premji Marg after that veteran motorcycle dealer staked its prominent corner - where my cousin Niloufer's family lives in the century-old Mahrukh Mansion. On the ground floor was Jehangir Irani, manager of Roshan Cinema, owned by his brother Pirojshaw who named it after his daughter. The Iranis climbed up to Niloufer's flat when rain flooded theirs, which was often. Waves swelled, Agripada Police Station to Maratha Mandir, with only D and N route double-decker buses wading through. Her reaction: "Yay, no school but story time with Jehangir Uncle, about Ballard Estate cafés and wartime songs he taught."

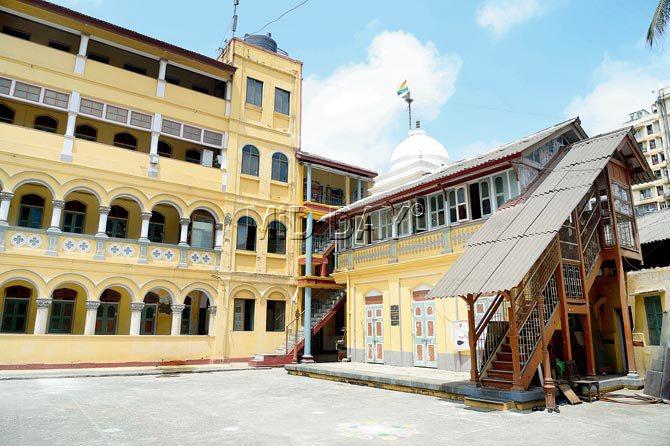

The traditional Indian with Neo Classical-styled Hirachand Gumanji Jain Boarding School has stood on Lamington Road since 1900. Pic/Suresh Karkera

The traditional Indian with Neo Classical-styled Hirachand Gumanji Jain Boarding School has stood on Lamington Road since 1900. Pic/Suresh Karkera

I turn into Uranwalla Path opposite Gilder Tank Maidan, the latter slated as the new metro station. The cul de sac seems frozen with early 1900s homes. A phone on the first floor landing of Merwan Building was the only one apart from a public booth at Grant Road station next door. Laughter in the cluster when, expecting her daughter late from a trip abroad, a woman bellowed over the wire: "Keys under the flower pot."

An amused overhearing chorus chimed, "Thanks for telling us Dolly Aunty!" No secrets, no distance, this is Everyman territory. The grocer pitches in to pay cab change you're short of. Issaq Bhai's watermelon sherbet cools customers for well over 60 years when he frothed an extra anna glass free for kids coming to his cart. He strode out in the 1993 riots and nobody touched the locality, says his wife Rehmat Bi - "He was respected, giving salaam-dua to all." For four generations Rajkamal Tiwari's chana stall has hailed regulars near Ghas Gully, whose hay in tabelas caught fires doused by the Byculla Brigade. Pigeons coo and cows moo on recognising the hands that feed them in the lane lined with car mechanics tooling away in garages.

From Auckland, where he settled after a Lamington Road childhood, Clive Cabral raves about the paaya masala of Marzban Irani's A-One Restaurant - Dev Electronics today. Suniel Shetty's father's café Ramanjanaya metamorphosed into a Thai restaurant before the current Saraswat Bank avatar. Except for longer lasting Geeta Bhavan, Shagun and Shree Sagar, eateries start and shut within Navjivan Society. Four of these colonies sheltered 1,600 post-Partition families, at Lamington Road, Mahim, Matunga and Chembur.

Raj Kapoor with Felix Rodrigues, director and manager of Apsara, at the 1964 premiere of Sangam, the theatre's first film. Pic Courtesy/Vanita Rodrigues

Raj Kapoor with Felix Rodrigues, director and manager of Apsara, at the 1964 premiere of Sangam, the theatre's first film. Pic Courtesy/Vanita Rodrigues

Our lunch spot is 98-year-old Veg Land, formerly Special Hindmata. Queues of customers in quest of tangy onion and potato bhajias would snake around its benches. "Our Punjabi and Chinese dishes are also a hit," says Ravi Salian, seeing us stick to tried and tasty uttapam. He manages Veg Land for his sister Asha, whose grandfather-in-law Mahindra Poojari worked his way up from cook to proprietor.

Facing the almost centurion Udipi is Ramsay House, HQ of Hindi horror flick kings. A bit of bhoot bangla itself, French windows and tin roof sheathed with a spreading siris tree planted by Karachi radio engineer Fatehchand U Ramsingh (foreigner colleagues Anglicised the surname to Ramsay). Few realise the ghost storyteller's foray was as co-producer of Shaheed-E-Azam Bhagat Singh, the martyr's first biopic, in 1954. Kumar, the eldest of Fatehchand's six sons, informs me his brother Arjun alone occupies the once bustling space.

On a road yet retaining its essential character, the saddest exits are staged by epic single screen theatres, left demolished or purveyors of soft porn behind rust-creaky iron gates. Those 1,000-seaters flashed House Full boards, red velvet carpets, silver jubilee bashes and industry blue blood Dilip Kumar and Raj Kapoor at glittering premieres. Cinemas of World War I were Imperial, West End, Minerva and Precious. Swastik joined them in the 1930s. Jawaani ki Hawa released at Imperial in September 1935 to controversy unrelated to the suggestive title. Franz Osten's romantic thriller had music scored by Saraswati Devi (Khurshid Minocherhomji from a conservative clan) and her sister Chandraprabha (Manek) as second heroine with Devika Rani. Demonstrating at Imperial, the Parsee Federal Council sought a ban. A fate the film escaped thanks to intervention from the predominantly Parsi board of its producer, Bombay Talkies.

Assigning themselves grand epithets like Pride of Maharashtra (Minerva) and Theatre Magnificent (Novelty), halls offered frills worthy of this film nagri - Naaz, for instance, reserved a soundproof room for mothers to hush bawling babies. "Lamington Road was my playground," says Tina Sutaria. Shashi Kapoor's neighbour, she would come down from Harkness Road on Malabar Hill with the actor's family to watch shows gauging aam aadmi responses to films like Kali Ghata.

Vanita Rodrigues was veritably wrapped in movie magic from her cradle in a mammoth 7,000 square feet penthouse atop Apsara, the theatre her father Felix was director of. He hosted cocktail parties at this apartment after inaugural shows of Sangam and Naya Daur among other celluloid classics. "December 3, 1971, when the Indo-Pak war broke out, was my Holy Communion Day," she recalls. Two blackout nights after, a shell dropped in our midst. Dad handed it in at Lamington Road police station."

Across the street from Allibhai Premji Tyrewala we chat with Dilip Shah in the 1910-built, delectably named Tottie Terrace, where his father Balkrishna set up Solar Tyres in 1953. Above their office was Kothawalas, then akin to Agarwal Classes, for math and biology tuition. Because everyone is their neighbour's keeper here, Shah shares how watermelon man Issaq Bhai was sports buff enough to invest in a Sony colour TV and National 340 VCR to follow the Asian Games held in Delhi's winter of 1982.

Shah recommends we stop to admire the traditional Indian with Neo Classical-styled Hirachand Gumanji Jain Boarding School. A quiet stunner of a building from 1900, this accommodates 90 out of town students, mostly chartered accountants staying three years to complete articles.

"It is more home than hostel," says Seema Javeri, whose husband Asit's great-grandfather Panachand Hirachand, with his brother Manekchand, established a trust ministering several such institutes across the country. This one fronts the beautiful wooden Suparshvanatha Mandir of the Digambar Jains, alongside Shravik Ashram. Originally the family house of Seth Panachand, later given as a home for widows, the ashram (erected by Seth Panachand on his young daughter losing her husband, with chawls from whose rent she maintained the house), is now a ladies boarding shala.

Another architectural gem, Pannalal Terrace, gleams opposite Parvati Mansion. It blends colonial with Neo Gothic design, I'm told by architect Puranjay Gandhi living here. Parvati was the second wife of jeweller Panalal Babu from Patan. His sons Jivanlal and Bhagwanlal owned Pannalal Terrace; a third, Mohanlal, owned Parvati Mansion. Panalal's great-great-granddaughter reveals Pannalal Terrace was bought by her ancestors around 1900 as a trio of income-generating chawl buildings from Seth Narsi Natha. These three were demolished for the expansive blocks A to H, housing middle class migrants of Junagadh and Rajkot's Nagar community from 1911. Gandhiji delivered a memorable speech at Pannalal Terrace on the afternoon of June 30, 1921, to collect funds for Tilak's Swaraj movement. Nationalist jewellers of the city gathered at the shamiana here to contribute a purse towards the cause. Home to Vinoo Mankad, that same compound witnessed many games of inspired cricket.

Clad in exquisitely embellished balconies and staircases, the residences are fronted by age-old Kabir Wadi Mandir and Grant Road High School, among snugly rowed paint and hardware stores, and Punjabi Ghasitaram Halwai since 1916. The prettiest ornamental chhatri shades Perry & Company chemists - across which Popular and Cultural Book Depot used to be names that said it all. At the 1948-opened dairy that Asif Quereshi inherited from his grandfather Usman and father Iqbal, I learn their bestseller is mawa samosa, mega ordered with litres of milk and lassi from 4 am daily.

Immersed in its charms, I lose track of hours spent tramping the road. The place has pulsated non-stop, sonic background boom and gabby chatter in overdrive. It is hysteria embedded in history, the clutter of vibrant culture. Yes, some streets are more special.

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at [email protected]

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!