In his new book, historian and environmentalist Dr Ramachandra Guha traces the multilayered thoughts and debates on environmentalism in early 20th century India

Dr Ramachandra Guha talks about his new book at the Bandra-based bookstore. Pics/Nimesh Dave

Wisdom demands a new orientation of science and technology towards the organic, the gentle, the non-violent, the elegant and beautiful.” These words are by the 20th century British economist EF Schumacher from his work, Small is Beautiful. They echo a common strain that runs through the historian and environmentalist Ramachandra Guha’s new book, Speaking with Nature (HarperCollins India). He traces the contribution of 10 thinkers of the 20th century, including Rabindranath Tagore, Mira Behn, Patrick Geddes and Kumarappa, who argued for sustainable and gentle ways of living at the time of high industrialisation. Most parts of the world had been witnessing a stark change in their economy, and colonial India was no different. Guha notes this period as one which marks the origins of environmental thinking in the country. The ideas emerged as a response to the large-scale felling of trees, excessive use of chemical fertilisers, lack of clean water, improper use and distribution of the resources in the farms, and gross levels of inequality.

ADVERTISEMENT

Guha stepped into the field of environmentalism by accident. We catch up with him at Trilogy, the Bandra-based library and bookstore, to understand how. He reflects on his early days as a researcher and credits his professors from his doctoral years at IIM Calcutta. On learning that Guha was from Dehradun, professor Jayanta Bandyopadhyay, a visiting faculty at the institute, had suggested that the Chipko Movement, with its roots in Garhwal, was something that he could look up. “There have been journalistic writings [on the movement], but there have been no sociological studies. Why don’t you write about it?” Guha recalls Bandyopadhyay’s words. “He had planted the idea in my head. Once I was in the field, I was consumed by it.” Forty years later, Guha continues to be a leading scholar in the subject, from having published his research on the Chipko Movement in his 1989 book, The Unquiet Woods, to his collaborative efforts with the ecologist Madhav Gadgil, his work on the global history of environment movements, and now, his latest endeavour.

Guha’s book explores the contribution of thinkers like

Guha’s book explores the contribution of thinkers like

The strength of Speaking with Nature is that the 10 thinkers essayed in it arrived at the subject differently, and were spread across various parts of the country. They collectively offered creative ways to tackle environmental hazards, most of them necessitating greater attention to the local communities, the poor and the dispossessed. Although MK Gandhi is not one of the thinkers, one can understand why he becomes a visible presence in the book. Guha tells us, “[This is] not principally because of his ideas on decentralised development but because Gandhi was the most important public figure of the time”. We learn how Kumarappa left Bombay to work on the survey project in the village of Matar in Gujarat for Gandhi. We also witness how Mira Behn (Madeleine Slade), Gandhi’s adopted daughter, worked in her ashrams in the Himalayan foothills with the peasants, advocating the need to return to manure over chemical fertilisers. Guha reveals, “The Gandhian strand of the environmental movement was strong in the 1970s and 80s. It was non-violent, looked out for local communities, and [fought] against large-scale destructive development.” Today, he urges those involved in developmental projects to understand Gandhi’s restraint.

He acknowledges that climate change is an immediate concern, instancing cyclones in the Coromandel Coast. The author argues, “Unfortunately, environmental debate has become only about climate change. Our path of industrial and economic development is unsustainable for a country that is so large and diverse, with such a dense population and fragile ecologies.” He adds how major problems like air pollution in several parts of the country, “biological death of our rivers, depletion of groundwater aquifers, and chemical contamination of the soil have nothing to do with climate change, but affect millions of people.”

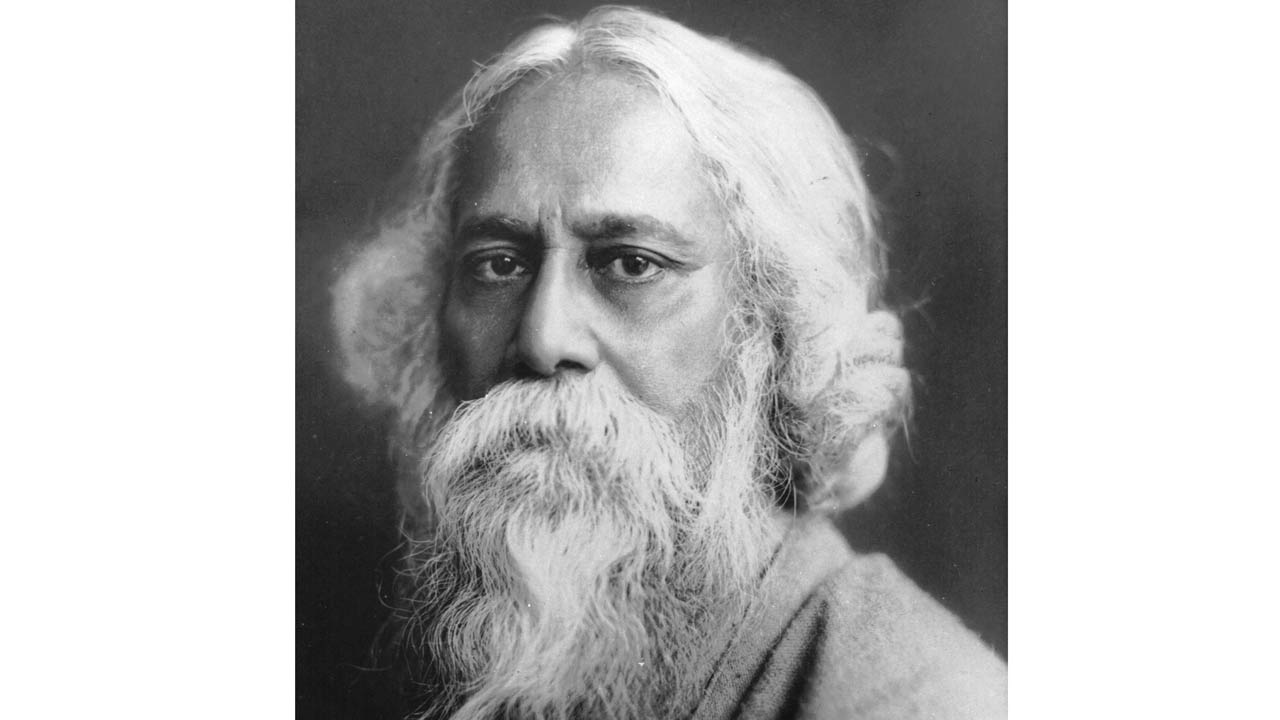

Rabindranath Tagore to environmentalism. Pic Courtesy/Wikimedia Commons

Rabindranath Tagore to environmentalism. Pic Courtesy/Wikimedia Commons

His experience in the field has allowed him to look for material that is not easy to come by: out-of-print work, letters, and pamphlets. “The more experienced you get, the more diverse places you end up digging.” This effort, he believes, is needed to stay clear of unethical practices. “Everything is not at the click of a mouse.” It can take years; for Guha, it was decades. “You’ve to look at all kinds of fugitive places.” Regretting that he could document only non-fictional accounts in his book, he is positive that there is a book somewhere to be written by a historian who can accurately document pieces of fiction, poetry, songs — mediums in which those in the periphery expressed themselves.

As for him, this is his last book on the subject — “I believe I have nothing more to say that is original at the length of a book”— though not his final piece of writing about it.

Available At leading bookstores and e-stores

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!