Historian William Dalrymple was in Mumbai to promote his new title. We caught up with the Scotsman, and discovered how this book situates India at the helm of intellectual and cultural transmission in the ancient period

William Dalrymple. Pic/Ashish Raje

Author and historian William Dalrymple is on the move. He’s wrapped up a studio shoot in Bandra, and has a lecture to deliver at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya in Fort. He stops for a conversation with us, and, in that moment, he has all our attention. His energy and excitement are infectious. “As a kid, my interests were archaeology and ancient history; I would spend all my school holidays digging on archaeological excavations. When I went to Cambridge, I studied archaeology initially, before changing to history. My 18-year-old self will be very surprised, as I ended up writing about the 18th and 19th centuries rather than ancient history,” he reveals. He recalls how, having first arrived in India 40 years ago in 1984, the first places he visited were the stupas at Sanchi and the caves of Ajanta and Ellora, guided by his original interest.

ADVERTISEMENT

A chaityagriha at Bhaja caves near Pune

A chaityagriha at Bhaja caves near Pune

“Having started the Company quartet [The Anarchy, White Mughal, Return of the King, and The Last Mughal], I got so absorbed in the period [of the 18th Century] that it took 20 years to write the four books.” He’s now moved on to exploring other subjects, which he admits, as an adult, he hasn’t been a specialist in. His latest book, The Golden Road (Bloomsbury), is his journey into unearthing a forgotten story of the ancient past. It’s a historian’s perspective on how Indian ideas — Indic philosophy, culture, and scientific discoveries — spread across the world through its sea and overland routes, and influenced other countries.

The façade of Cave 10 at Ajanta

The façade of Cave 10 at Ajanta

Dalrymple offers a detailed study, first, of the early days of Buddhism and its rise in regions west of India during the period of Ashoka, and then, of its diffusion into various parts in Southeast and East Asia. Such details are drawn primarily through its carriers and bearers. The characters make the text: Shakyamuni, Ashoka, the Yavanas, the Yuezhi, the Nalanda monks, the Chinese empress Wu Zetian, and the Pallavas. Dalrymple writes like a novelist but there is no fiction in his work. It’s backed by his reading of existing scholarship on the ancient world and his study of wall paintings, art history, and numismatics. “India has an extraordinary story to tell,” he says. The number of footnotes in the book is testimony to his effort to tell the story as it is, “to give a straightforward, neutral, and factual account that’s not a sort of chest thumping work of nationalism.” His amazement does not preclude his laying down of the facts.

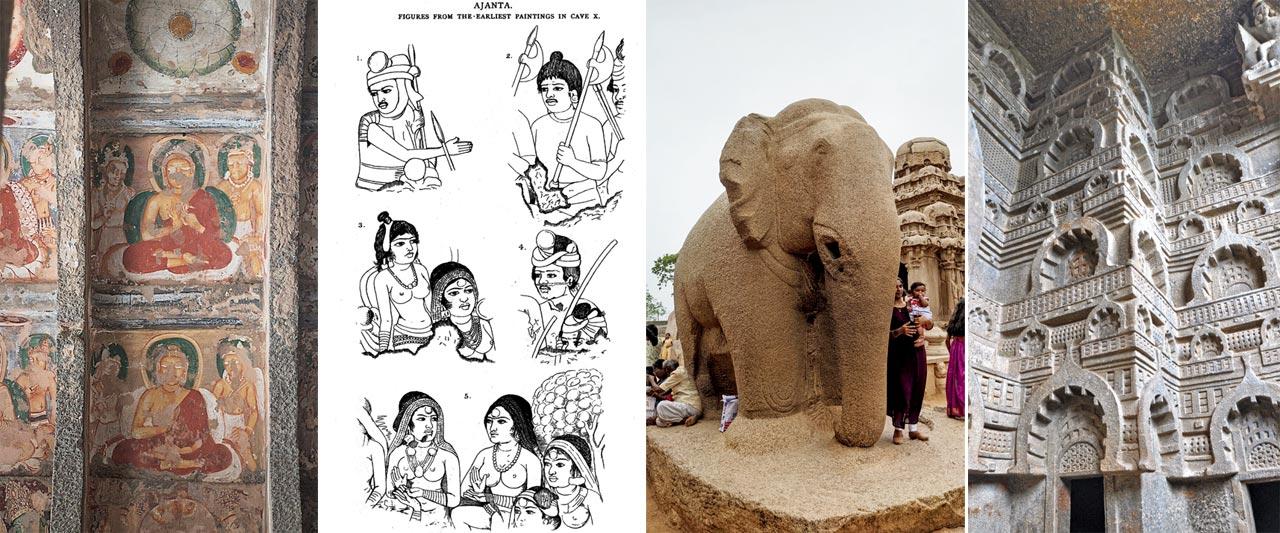

A mural of Buddha in Cave 10 at Ajanta; Illustrated figures of Ajanta Cave paintings; Stone elephant at the Pancha Rathas of Mahabalipuram; Buddhist rock-cut façades at Bedsa Caves near Pune. Pics Courtesy/Wikimedia Commons

A mural of Buddha in Cave 10 at Ajanta; Illustrated figures of Ajanta Cave paintings; Stone elephant at the Pancha Rathas of Mahabalipuram; Buddhist rock-cut façades at Bedsa Caves near Pune. Pics Courtesy/Wikimedia Commons

Ancient India lacks enough manuscripts, he shares. “Anyone who deals with ancient history has to scrape around at a much more varied set of sources.” For instance, we learn that the earliest phase of Buddhism, 450-250BCE, had no inscriptions. “It’s only with Ashoka [and his edicts] that we start to get epigraphic evidence of the religion.” This is fairly different from the work that the colonial period demands, where, he believes, one is truly spoiled for choice. “There are so many good letters and diaries. There are 30 miles of records in London, and a comparable amount in the National Library in Delhi.” As for ancient history, he reveals, “For great swathes of this period, you’re in the dark. And then suddenly, you come across lucky survival, and the lights go on, as with Xuanzang (Hsüan-tsang). Suddenly, you have not just Xuanzang, but his biographer, and a whole world associated with his protégé. And then you dive into another darkness again.”

In searching for the light, Dalrymple arrives at his thesis on India’s position as “a crucial economic fulcrum and civilisational engine... one of the main motors of global trade and cultural transmission in early world history… on par with China.” He argues that what we know as the Silk Road today is, in fact, a modern idea. “One of the things that happens with historians is that they pick up and echo each other.” Several ideas dominate; these are not necessarily facts. “The Silk Road seems to be a very good example of how, for various reasons, a half-truth has become an established fact. Now the Silk Road (trade routes connecting China and the Far East with the rest of the world) certainly existed in the 13th Century when Marco Polo used it. But whether it existed in any tangible sense in the classical period is highly questionable.” Yet today, two shows in London speak about the Silk Road and reinstate a stance that is actually a myth. Dalrymple believes that ancient China and Greece have been very good at telling their stories. But India has suffered in comparison with the two.

Two sections in the book stand out: his exploration of the spread of literary texts (outside of the epics), such as the philosopher Dandin’s The Mirror of Poetry (Kavyadarsha), and his inclusion of astronomical and mathematical discoveries by Aryabhatta and Brahmagupta. Few know of the origin of zero outside of India; yet fewer know that what the West calls “the Arabic number system” actually began in India. The startling dispersal of Indic ideas was “a relay race”. They began in Pataliputra, moved to Mount Abu, Sindh and Baghdad, were translated by Al Khwarizmi, entered Spain, and reached Italy through Fibonacci, “two generations later, Leonardo da Vinci was reading this material.” In the end, Dalrymple’s work nudges us to think about what we can learn from ancient India — not the hierarchies but alternative philosophies, its culture and scientific discoveries, its scholarship, poetics, and critical inquiries.

Dalrymple’s reccos for site visits

. Ajanta Caves

. Early Buddhist cave monasteries outside Pune: Bhaja, Bedsa, and Karla

. Pallava temples in Mamallapuram (Mahabalipuram) and sites around Kanchipuram

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!