A doctor, a politician and an entrepreneur extraordinaire journeyed to Bombay, for dramatically different reasons, and all to remarkable result

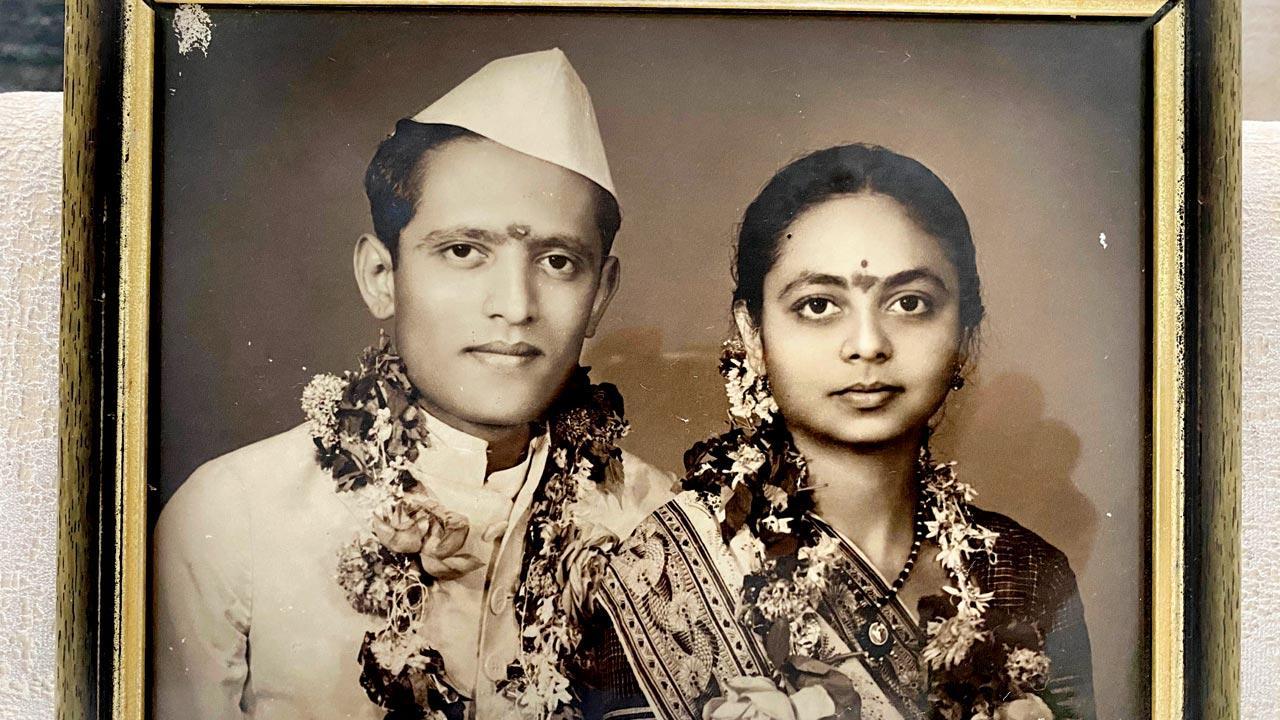

Urmila Vashi and Amul Shah on their “secret” wedding day in 1951. Pics courtesy/Avani Shah

She wanted to board a Bombay-bound train, but climbed one chugging in the opposite direction. Urmila Vashi had come home to Navsari on a break from Grant Medical College (GMC) in Bombay. Every bit as bold as she was bright, she was determined to marry her classmate Amul Shah and chart a future together.

ADVERTISEMENT

The family forbade her leaving Navsari to meet her beau again. Apart from the fact that she was fixing her own match and with someone still to settle financially, their opposition owed to time-worn prejudice—the couple belonged to different Gujarati castes.

The freshly qualified young doctor

Embarking on an adventure incredible for a girl alone to attempt in 1951, Urmila sneaked into Navsari Station. With no train to her destination scheduled for hours, she began walking on the opposite track. Towards Surat, to throw pursuing relatives off-scent. A surprised motorman heading there in his solitary engine picked her up.

Realising she needed to reach Bombay, he requested a colleague going her way, for a ride. She switched engines at Surat, jumping on in a puff-sleeved frock, the tailored trend of the day. Till the Bombay finale it was for the romantic escapade straight from a masaledaar Yash Raj movie.

“She thought the getaway neither brazen nor remarkable, simply what must be done. Mummy was a gutsy feminist, considering her traditional background,” says her dermatologist daughter-in-law, Dr Avani Shah.

Grant Medical College, their alma mater. Pic/Shadab Khan

Awaiting his plucky bride-to-be in Bombay with admiration and trepidation, Amul knew little could deter her en route. Urmila had shone right from her years at Tata School near Tarota Bazar in Navsari, where she studied intently on her otla porch. “Vashi ni naanhi dikri bau hushyaar ([Manibhai] Vashi’s younger daughter is so clever),” the mohalla buzz marvelled. Her studious bent exempted her from an overload of household chores.

She stayed with an aunt in Ahmedabad to complete her Junior BSc—a taxing period with nights spent reading textbooks under the streetlights. Travelling to college, she was harassed by a roadside Romeo for two days at her bus stop. On the third morning, a Muslim shopkeeper, noticing her discomfiture, had laid a charpoy at the spot to sit separately.

SK Patil and Sardar Patel at Robert Money School in the 1950s; Patil with his beloved dog Tinker. Pics courtesy/Suhas Thakur

At GMC, Urmila and Amul became instant, constant companions. For final exams, she wheedled him into underlining salient paragraphs in medical tomes. She focused on those marked sections. He diligently memorised copious whole chapters. She passed.

He ducked.

“On graduating, they practised as general physicians, him with more than a working knowledge of paediatrics, her of gynaecology. My mother was among Bombay’s first to earn an MBBS-DGO (diploma in gynaecology),” says orthopaedic surgeon Dr Nilen Shah.

Out-of-towners both—he from Bhavnagar where his father ran A to Z Provisions—they had sought hostel accommodation. From Mahavir Jain Vidyalaya at Gowalia Tank, he commuted to GMC on foot, sparing precious tram fare annas. She lived in Kanji Khetsi Girls Hostel in Fort. Soon after that exciting train trip, she dressed for their secret wedding from a hostel room on the top floor of Mani Bhavan.

Cooper greeting Indira Gandhi at Bombay airport. Pics courtesy/Farhad Cooper

Four years following that clandestine ceremony, the official 1955 marriage—when Urmila Vashi became Pushpa Shah—was blessed by a now mollified family. The Shahs split rent with another family in Ghelabhai Mansion at Chowpatty. They shared a clinic round the corner at Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. Their prem kahaani kept blooming through almost 70 summers. The city lost Dr Pushpa Shah two years back at a grand 92.

Landing here for higher education a generation earlier, a policeman’s son from Zarap village of Sindhudurg went on to be “anabhishikt samraat”, the uncrowned king of Bombay. The articulateness moulding Sadashiv Kanoji (SK) Patil into a fine journalist and consummate politician was evident at age 12. His granddaughter, Natya Sangeet singer Sumitra Samant, reveals he reeled off Bhagavad Gita passages in Sanskrit at kirtan gatherings.

Finishing from the local school he trekked four miles to daily, Patil enrolled at St Xavier’s College. “His affinity for a cosmopolitan Bombay formed on this campus. He gave up studies in 1921 to participate in the Non-Cooperation Movement,” says grand-nephew Suhas Thakur, whose father Maheshwar Vishnu Thakur was virtually Patil’s personal assistant.

Keki Byram Cooper

An outstanding orator in Marathi and English, Patil studied journalism at London School of Economics, encouraged by philanthropist and fellow Malvani, Motiram Desai Topiwala. Returning, he lent his patriotic pen to the Bombay Chronicle, edited by that Englishman champion of free India, Benjamin Guy Horniman.

Patil told his grandchildren, “You have a golden spoon in your mouth. I suffered unforgettable hardship.” Steeped in the disciplined idealism of satyagraha, he was jailed eight years between 1930 and 1944. His family lived in Sita Building, close to Congress House. The chawl with stunning timber railings and infilled louvers lies off VP Road, named after Vitthalbhai Patel, Swaraj Party co-founder and brother of Patil’s mentor Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel.

His public career soaring, Patil was Bombay Provincial (later Pradesh) Congress Committee general secretary for 17 years from 1929 and its president for another decade from 1946. With rallying cries of “sakriya swatantrya”—active independence—Bombay emerged the country’s power centre.

From 1930 to 1967, Patil was unquestioned leader of the Congress, notes TK Tope in the book, Bombay and Congress Movement. “Friends with all parties, he was called ‘the practical politician’ by US presidents Lyndon Johnson and JFK,” adds Suhas. Patil served three consecutive Mayor terms among civic posts of distinction.

The avowed animal lover doted on Labradors and boxers. Whenever Vijaya Raje Scindia—part of Patil’s inner circle, with Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Tarkeshwari Sinha—came to Bombay, she gifted him smaller dogs.

As Union Minister for Railways in the mid-’60s, he helped social worker Bapsy Sabavala save a Matheran horse. Seriously wounded, championship-winning Super Boy deserved attention from Parel’s Haffkine Institute. Transporting large animals by train was unprecedented. Sabavala fake-signed a telegram from Patil instructing Central Railways, declaring, “I’ll explain to Patil. He’ll understand.” He absolutely did. Super Boy survived.

Also 1927-born like Dr Pushpa Shah was Keki Cooper, the son of a successful Lahore barrister, forced to ditch privilege. In Bombay, he reset the brutal legacy of Partition, emerging a dynamic entrepreneur and visionary innovator.

Leaving behind a luxurious 13-room villa and repute enough to have Street 13 and 17 named Cooper Road, the 20-year-old rode the fateful last train from Lahore in 1947. Braving bloodied platforms piled with bodies, with his father Byram, he pulled up a sepoy fighting for a foothold in their compartment. Only these three Indians stepped off alive, besides four Britishers under Army escort.

Father and son were fleeing to reunite with Keki’s mother Shirin, who was visiting her parents in Secunderabad—her father Pherozshaw Chinoy, financial advisor to the Nizam, built the Hyderabad fire temple. Rather than Shirin risk a solitary comeback to Lahore, the men decided to reach her. Not being “Mulki”, native to Hyderabad, and Lahore part of undivided Punjab, Keki was refused college admission. He shifted to Bombay, where the Dubash side of his father’s family took him on at Darabshaw B Cursetjee & Sons, their shipping major with multiple interests.

Starting as salesman at a cold storage, he was subsequently employed with the famed Rogers fizz brand. It was jobbing at Kandla in Gujarat that paved the path for seven decades of expertise in shipping, bulk cargo handling and stevedoring. “Rising from dockhand to foreman, converting a salt port to a thriving commercial one, he was a member of the Ports Advisory Committee of Gujarat Maritime Board and president of Kandla Steamship Agents Association,” says Keki’s son Farhad, MD of Amfico Agencies, which his father bought in 1965.

The company commenced operations representing carpet auctioneers Rippon Boswell and Bickenstaff and Knowles, before becoming the face of UK logistics giant, Suttons International. Cooper won the first contract in an unusual encounter. Sam Wennek of Rippon Boswell, was a Swiss Jew known to Cooper’s friend Reuben Kelly. At a Colaba synagogue, Kelly introduced Cooper to Wennek as the man swinging a vastly better than expected price for a car sold. Impressed, Wennek offered him the carpets deal. Striking business within 48 hours, Cooper fit the bill perfectly—Wennek preferred Parsi collaborators.

Cooper was further instrumental in developing the Jamnagar, Bhavnagar, Magdalla, Dahej and Pipavav ports. Chief Minister Chhabildas Mehta credited him in a letter, for facilitating dual fuel technology, moving automobiles on gas and petrol before their debut in India. “Many of his pioneer projects lack documentary proof. Dad presented the government proposals like linking the Ganga to the hinterland up to Kanyakumari with canal irrigation,” says Farhad.

I once interviewed Keki Cooper—feisty, few traces of fragility even in his 90s—for a history of Altamont Road. He came in 1964 to Navjeevan Kutir, where his beautician wife Kamal opened her popular salon. From their kitchen window they watched Rolls Royces purr out of the tycoon Dadiseth’s Greek-style mansion, which is Prithvi Apartments today.

Any advice, I asked. “Bad times, great times, come and go. Just remain full of ideas and plans till the very end.”

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at [email protected]/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!