The lipstick, a marker of identity and zest, turns metaphor in Roshan Chhabria’s new solo show, where the visual artist decodes the social mores of middle class India

Roshan Chhabria seated in his Baroda home

![]() There is a reason why used objects—signboards, a coal iron press, a telephone with the classic bell ringer, an aluminium measuring can, a scooter seat—find their way into visual artist Roshan Chhabria’s studio space. He is attracted to such found objects on an impulse; he invariably carries them home, despite the risk of ridicule. While he braves admonishment (“Sintex taanki kyun nahi laaye?”) at the hands of loved ones, a narrative emerges in his mind, enabling him to envision the object on his canvas, or in an installation. The object then becomes his medium for telling a truth about his own life, or the social situation around him, Chhabria writes in his Master’s thesis titled About Myself. It was a dissertation submitted in 2013 to the Department of Painting, Faculty of Fine Arts, MS University, Baroda.

There is a reason why used objects—signboards, a coal iron press, a telephone with the classic bell ringer, an aluminium measuring can, a scooter seat—find their way into visual artist Roshan Chhabria’s studio space. He is attracted to such found objects on an impulse; he invariably carries them home, despite the risk of ridicule. While he braves admonishment (“Sintex taanki kyun nahi laaye?”) at the hands of loved ones, a narrative emerges in his mind, enabling him to envision the object on his canvas, or in an installation. The object then becomes his medium for telling a truth about his own life, or the social situation around him, Chhabria writes in his Master’s thesis titled About Myself. It was a dissertation submitted in 2013 to the Department of Painting, Faculty of Fine Arts, MS University, Baroda.

ADVERTISEMENT

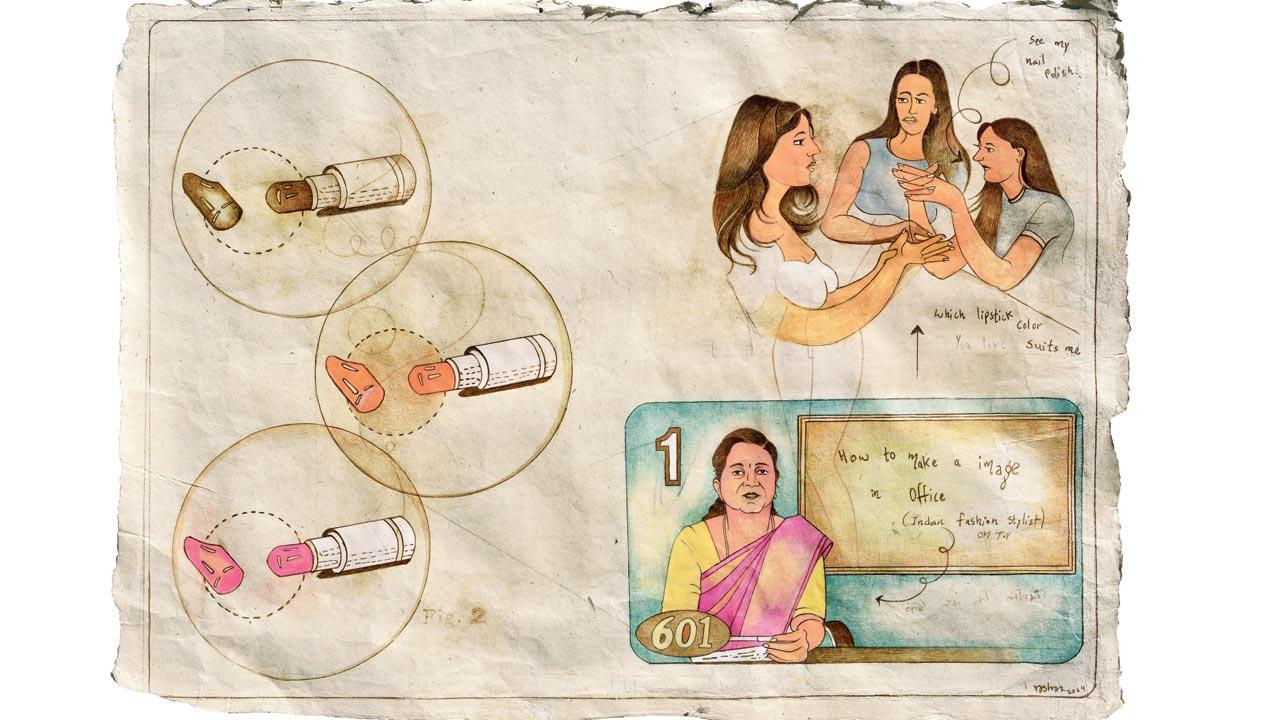

Despite the passage of time, Chhabria’s enchantment with found objects remains constant. In his latest solo show, which opened at Sakshi Gallery, the Baroda-based artist presents Lipstick Stories—cute, quirky, intimate and reflective portraits of men and women leading ordinary, essentially middle-class lives. “These are vignettes of middle class existence around me, in Mumbai, Baroda or any Indian city. Of the 16 paintings in the show of varying dimensions and sizes, three revolve around lipsticks, but they set the overarching tone and tenor,” the visual artist says.

A work from Lipstick Stories, Chhabria’s new solo show at Mumbai’s Sakshi Gallery

A work from Lipstick Stories, Chhabria’s new solo show at Mumbai’s Sakshi Gallery

“To me, a lipstick is a symbol of vitality, freedom, zest and an in-your-face expression.” Chhabria adds that it was gallery director Geetha Mehra who helped him zero in on the show’s title.

Growing up in a Sindhi family in Baroda is part of Chhabria’s oeuvre as well as his identity; it shows in Lipstick Stories, too. “You can see signs of my Sindhi roots in my colour palette. One work dwells on the gaudy, red lipstick that a new widow is asked to abandon; another shows three flashily dressed office-going women discussing the colour of their nail polish,” he explains. The artist uses a variety of materials—plywood, used signboards, paper, canvas—to convey his point of view. Text, in thought bubbles and as an element unto itself, is integrated into his art. For instance, the katori blouse perfection emerges in its totality and the flour mill comes alive with a gehu/bajra pisai rate card.

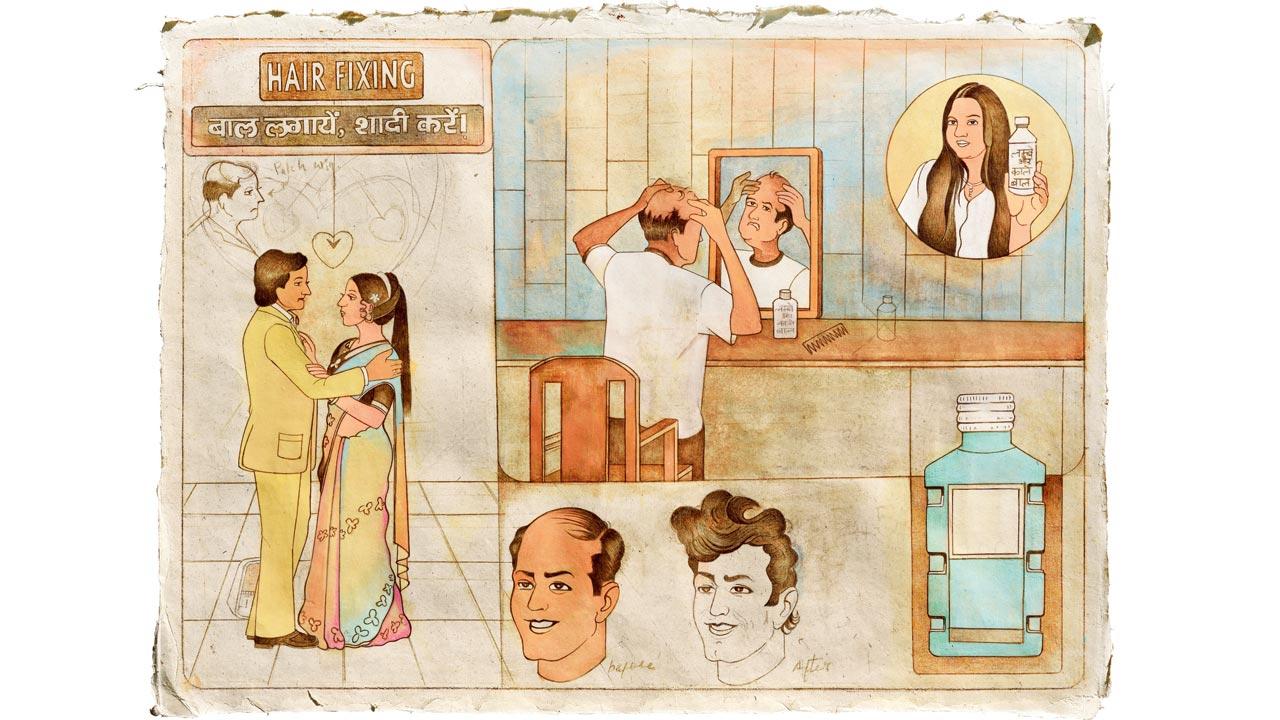

Hair Fixing Moments

Hair Fixing Moments

Chhabria’s earlier works, too, draw from his Sindhi social context. For instance, one work (2011) took a dig at a Sindhi marriage bureau. A past installation commemorated the community’s fixation with papads; he juxtaposed edible papad props with drawings of archetypal Sindhi women. “One of my watercolour works depicts a newly-married departing daughter being given a bag of papads as a dowry gift. I see these cultural choices as educational; these works are therefore as much about me as they are about other Sindhis,” he says.

His first solo show, Ideal Boy (2013), was also a summary of his humble beginnings in a Sindhi family that migrated after Partition. Ever since, the joint family has run a suiting-shirting shop in the neighbourhood of Mandvi, which Chhabria occasionally attends to even today, notwithstanding his career in the visual arts. Ideal Boy takes an oblique look at the twists and turns of his life, which guided him towards out-of-syllabus choices—that proved to be far from ideal. He never paid heed to posters and charts which list “good habits” for the Adarsh Yuvaan Balak. Contrary to the rules, which dictate that boys wake up early, bathe, pray, go to school, play and socialise, young Roshan was neither a willing helper in the family shop, nor an academic success. He failed every subject in his first year of Commerce at college and secretly opted for Fine Arts.

It’s not that he loved art; the course was a way to get closer to a girl he liked. “I wasn’t looking at the arts with any long-term goal. But things just clicked and I did well. When I won gold medals in both the BVA and MVA programs, the MSU faculty on the Commerce side was shocked to witness my growth. My convocation seemed like a revelation for them.” Chhabria says the arts program catalysed his creativity, and the campus enabled him to take a dispassionate look at himself. “I could laugh at myself, my quirks, my surroundings,” as he puts it.

Lipstick Stories is a new manifestation of Chhabria’s ability to address both the personal and the political in his art. For instance, the painting on “Ganjepan se chutkara” (Freedom from hair loss and baldness) touches upon a concern that is universal as well as personal for the artist. “My receding hairline was always a source of insecurity for me, especially when I was searching for a life partner. I think the world of remedies, lotions, oils, and tablets emerges strongly in my works due to this reason. Art is personal to a large extent,” he says in retrospect.

Like baldness, tailoring and garments, too, feature prominently in the Lipstick series. The work, Naap Leneka Sahi Tarika, captures the politically and socially awkward institution of the ladies’ tailor. In an earlier work titled Picasso Ka Mardana Pant (made with enamel paint and watercolours on a board) Chhabria puts forth an interesting comparison between Pablo Picasso’s geometric paintings and a local tailor’s measurement maths. Similarly, the local enterprise is celebrated in his works—be it the stealthy nature of Happy Royal Spa, the standards set by Vishwas Atta Chakki, a potato chips manufacturer, or the porter offering aaram gadlas (mattresses) on rent.

Chhabria’s aesthetic is distinct, capturing the seedy, ramshackle, somewhat unclean corners populated by small-time art dealers, tailors, police constables, barbers and dosa makers. All of his works offer a slice of unfolding life, whether it is a cookery show, or a delinquent student caught doodling in Maths class, or eligible bachelors showing off their “Hamara Bajaj” scooters to attract potential matches. “I see colour in all ordinary exchanges; the people around me unknowingly gift ‘ways of seeing’ things to me. Even pop culture films impact my aesthetic choices. I was particularly influenced by the Gangs of Wasseypur series—films which generated so many memes, posters, catchphrases, and what not.”

Even as Lipstick Stories welcomes visitors, Chhabria is charting another exhibition, on the Sindhi community based in Ulhasnagar and its ripped-off versions of high street brands. “As a fellow Sindhi from another city, I am curious about the effort and ideation that goes into fake Diesel, Nike and Puma. I am not passing judgements; but these are portraits of the community, with a focus on their ingenuous wares. I want to acknowledge the huge market they create.”

As for this columnist’s own lipstick connect, it was a no-no at my Kendriya-Vidyalaya-in-the-Seventies set-up; during my college days, it became an occasional indulgence. Rekha’s dark red lipstick in Silsila was a matter of awe and the subject of family gupshup. Later, my Aai “approved” a bright rust lipshine for my wedding and other life-transforming events, though subdued mauves and browns had greater acceptability in our social circle. The reds invited censure.

I experienced complete lipstick autonomy only after my thirties; until then, chapsticks and petroleum jelly were my self-imposed, pro-health choices. Now in my fifties, I opt for lipsticks with a vengeance. I pride myself on nurturing the talent of rolling it on my lips without using a mirror. I have many dark shades—unbothered about skin tone matches—and it seems to be out of a sense of admiration for younger, experiment-driven colleagues. During the pandemic, what I missed most was the going-out-for-a-play-with-lipstick-on vibe. Chhabria’s Lipstick Stories brought back memories of my own!

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at [email protected]

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!