A new book exposes how gender bias and stereotypes stall women’s careers in Mumbai’s corporate universe

Dr Samapti Guha (left) and Dr Sanskruti Kadam, photographed at the TISS campus in Chembur, perceive Mumbai as an interesting test case because of “the high speed of sociological changes”. Pic/Shadab Khan

![]() Does metallurgical engineering pose a specific security hazard for women? The question sounds out of place in 2024 when women in STEM fields are being increasingly encouraged by mentoring networks to give their fullest potential to the chosen streams. But the question is surprisingly central to a real-life incident in a female engineer’s life; she was informed by senior management that the production zone was off-limits for women engineers in the interest of their safety and security. She was assigned to a role in HR, far removed from her expertise and aspirations.

Does metallurgical engineering pose a specific security hazard for women? The question sounds out of place in 2024 when women in STEM fields are being increasingly encouraged by mentoring networks to give their fullest potential to the chosen streams. But the question is surprisingly central to a real-life incident in a female engineer’s life; she was informed by senior management that the production zone was off-limits for women engineers in the interest of their safety and security. She was assigned to a role in HR, far removed from her expertise and aspirations.

ADVERTISEMENT

The metallurgical engineer who was positioned in the office—while her male colleagues visited mines and smelters—is one of the many voices that populate An Inquiry into Women Representation in Management: A Case Study of Indian Industries (Springer publication) by Dr Samapti Guha and Dr Sanskruti Kadam. The engineer met the authors around 2018; she is currently happy in a workplace where her on-site decision-making is valued.

The study factors in 22 industries (as varied as banking, IT, finance, pharma, jewellery, fertilizers, shipping, media, petrochemicals), 68 companies and 560 respondent executives from Mumbai. In academic terminology, Guha and Kadam combined two kinds of analyses—exploring (exploratory factor analysis) factors under four (personal, work, social, organisational) dimensions that determine women’s representation; and measuring (confirmatory factor analysis) their influence on career growth.

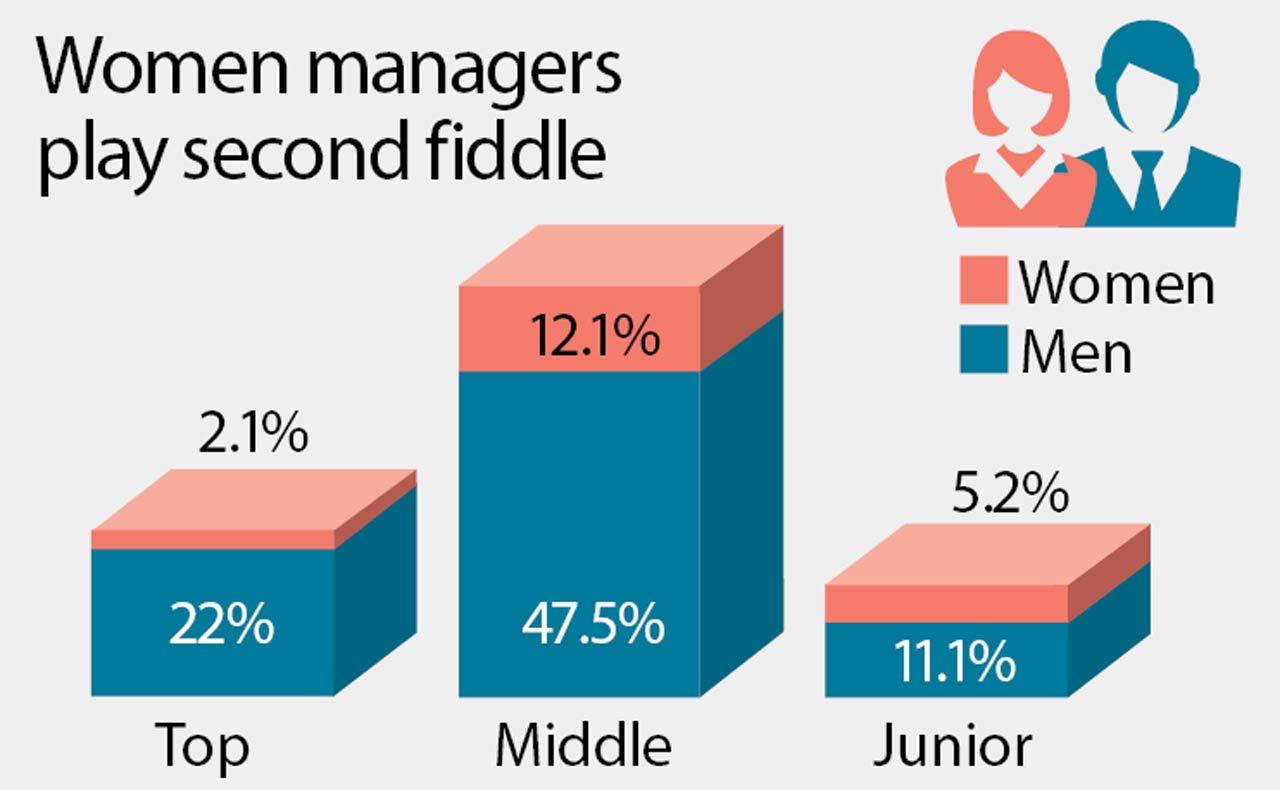

Data in the book shows how women form a minuscule proportion of top level management in Mumbai companies

Data in the book shows how women form a minuscule proportion of top level management in Mumbai companies

Findings are in the form of percentages and extrapolations; experiences and opinions are recorded in demographic categories. For instance, just as women’s representation is impacted by age, marital status, children/dependents; it has a connect with academic qualifications, career breaks/gaps, duty-type choices, work durations, and salary expectations. Respondents’ names are kept anonymous. Before the current study, the authors had piloted a project supported by Indian Council of Social Science Research (2015-16) on 300 managers. Later, they held workshops for women entrepreneurs in India. “We found a significant number of entrepreneurs started their enterprises after they faced barriers in their corporate careers. Some of them reached top-level management but could not overcome the problem of gender inequality,” affirms Dr Guha.

The choice of Mumbai as the backdrop doesn’t stem from the fact that both authors belong to the city. They see the metropolis as an interesting test case because of “the high speed of sociological changes over here compared to other parts of India”. They cite that within the last two decades, working mothers in Mumbai transitioned from an exception to being major players in the Indian corporate world. Also, despite being the corporate nucleus of the country, Mumbai’s business landscape is characterised by the presence of glass ceilings, glass walls and glass cliffs. The voices of Mumbai’s women reveal restrictive gender roles, stereotypes, and biases that adversely affect career development. The book factors in male voices too.

“It is crucial to know how the male counterparts perceive women in management. Not all male managers support gender discrimination. Men can be allies; they learn from women and vice versa,” says Dr Guha who is a professor at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences’ Centre for Social Entrepreneurship, who has researched microfinance, women entrepreneurs and financial inclusion. She did a research project on financial health of slum dwellers during the COVID-19 pandemic; she writes on the role of rotating savings/credit associations in Mumbai’s slums, especially Dharavi, Shivajinagar, Baiganwadi, Mankhurd, Cheeta Camp, etc. Dr Kadam is currently dean of Sasmira’s Business School.

For a proud Mumbaikar who believes there’s no more progressive city in the world, the book shows negative shades prevalent in the maximum city—the higher up an organisation’s hierarchy, the fewer women are able to ascend the ladder. The Indian trend and truth aligns with global trends of women rising to managerial positions at a slow, uneven and sometimes discouraging rate.

The age of Mumbai executives in the study ranges between 22 and 67 years, with an average age of 38. The low presence of women executives is due to gender stereotypes, discrimination, harassment, and the challenge of balancing family and work responsibilities. When women executives have similar educational qualifications to men (some hold doctoral degrees), academic trajectory does not guarantee industry success. Few women executives reach the top level. Due to personal and social reasons, such as the responsibility of childcare and family care, women executives have taken career breaks and their duration of work in an organisation is much less than that of male executives. Most Indian industries do not have formal policies regarding flexihours for child/ family obligations.

It is cited that several organisations till date practise caste and gender discrimination from the stage of recruitment to the stage of awarding promotion. Gender wage gap and gender segregation of work exists at all levels. Even in assignment distribution, there is a bias against women. Both manufacturing and service sectors betray gender-based discrimination. Things have changed a bit over last decade; a large number of respondent executives had joined the industry during 2001–2010.

The best part of the book is that it positions the Mumbai sample study within the global context. It references geopolitical crises (Ukraine war and post-COVID stagflation) which reduced the employment of women and youth at a very sharp rate. As per the global data quoted by the book, among companies which do not have compulsory gender quotas, 20-30 per cent boards have women directors, and 23 per cent do not have any women directors (Catalyst, 2022). Globally, 36 per cent of private sector managers and public sector officials are women.

An Inquiry into Women Representation in Management... devotes considerable bandwidth to constructs like gender versus sex, masculinity/femininity, and patriarchy, which help an Indian reader understand why women often play second fiddle in India. Various definitions of feminism are analysed threadbare—while psychoanalytic and gender feminists believe “women’s way of acting is rooted deep in women’s psyche”, the ecofeminists state that the woman-nature association is the cause of both sexism and naturism.

The book factors in economic expansion and technological innovations as contributing to women’s success. In 2013, India passed a law necessitating each public listed company to have at least one woman on board. The constitutional framework advocates equal rights and privileges for all; it demands provisions for women’s welfare. India has a firm foundation of gender equality, which of course needs to translate into policy, with the right political will!

The study cites strategies adopted by “successful” women to break the glass ceiling. One female manager commented that personal relationships are central to career success. “Domestic maids, caretakers and even your husband, ... take everybody in your journey....”

According to many respondents, they rely on organisational support policies, be it a creche in the workplace or leave for family care. Also, author Dr Guha advocates that when women get a chance to represent top leadership, they should focus on organisational policies to help other women grow. They should also sensitise organisations to the long-term cost of losing women talent.

Both authors urge other scholars to take their work forward in two forms—focus on second/third-tier metros which are characterised by gender stereotypes; and investigate women’s roles in heavy engineering/defence manufacturing industries which have male managers for long.

Sumedha Raikar-Mhatre is a culture columnist in search of the sub-text. You can reach her at [email protected]

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!