Rajinder Krishan’s 105th birth anniversary merits a look at his outstanding lyrics, defining the Hindi film industry’s classic black-and-white era and entertaining fans with eternal romantic hits

(From left) Qateel Shifai, Rajinder Krishan, Naqsh Lyallpuri, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Naushad, Dev Anand, Pran, Hasan Kamal, Yash Chopra and Gulshan Rai at a private gathering. Pictures Copyright and Courtesy/The Duggal Family

Some stories have a surprise inception. The idea for this one sprang in the middle of dancing to “Eena meena deeka” at a recent wedding. “That’s my dad’s song,” our friend Bobby Duggal, drummer of Indus Creed (formerly Rock Machine) band, turned to tell me and my husband. I nodded, struck by the sheer versatility marking the oeuvre of his father, the legendary lyricist Rajinder Krishan Duggal.

Some stories have a surprise inception. The idea for this one sprang in the middle of dancing to “Eena meena deeka” at a recent wedding. “That’s my dad’s song,” our friend Bobby Duggal, drummer of Indus Creed (formerly Rock Machine) band, turned to tell me and my husband. I nodded, struck by the sheer versatility marking the oeuvre of his father, the legendary lyricist Rajinder Krishan Duggal.

ADVERTISEMENT

Showered with epithets, from shaayaron ke shaayar and mahaan geetkaar, to king of song and badshah of the ballad, Krishan composed chameleon-like. Literally switching tracks with consummate ease, he could create the syllabic tongue-twists of “Eeena meena deeka” (Aasha, 1957) and more soulfully frame “Suno suno ae duniya waalo, Bapu ki yeh amar kahani”. Set to tune by the film industry’s first musician duo, Husnlal-Bhagatram, this paean to the slain leader, within hours of the 1948 assassination, resonated nationwide.

Rajinder Krishen with wife Savitri and family at their daughter’s wedding

Rajinder Krishen with wife Savitri and family at their daughter’s wedding

The man who made magic with Hindi moviedom’s greatest musicians, writing 1,600 songs in over 260 films, was born at Jalalpur Jattan in undivided India on June 6, 1919. “The third of four brothers, he was passionate about poetry, smuggling pamphlets of shaayari passages between pages of his school textbooks,” reveals his filmmaker nephew Satish Duggal. “That habit influenced his unique perception later, sharply spotting details people seldom notice.”

Moving to Simla to join his eldest brother, Krishan was barely 15 when he attended the annual all-India mushaira the hill town hosted. Encouraged by Sahitya Akademi winner Jigar Moradabadi, he presented an original verse to an enthralled audience. Interestingly, though reciting shaayari with a beautiful lilt, he was unable to hold a note.

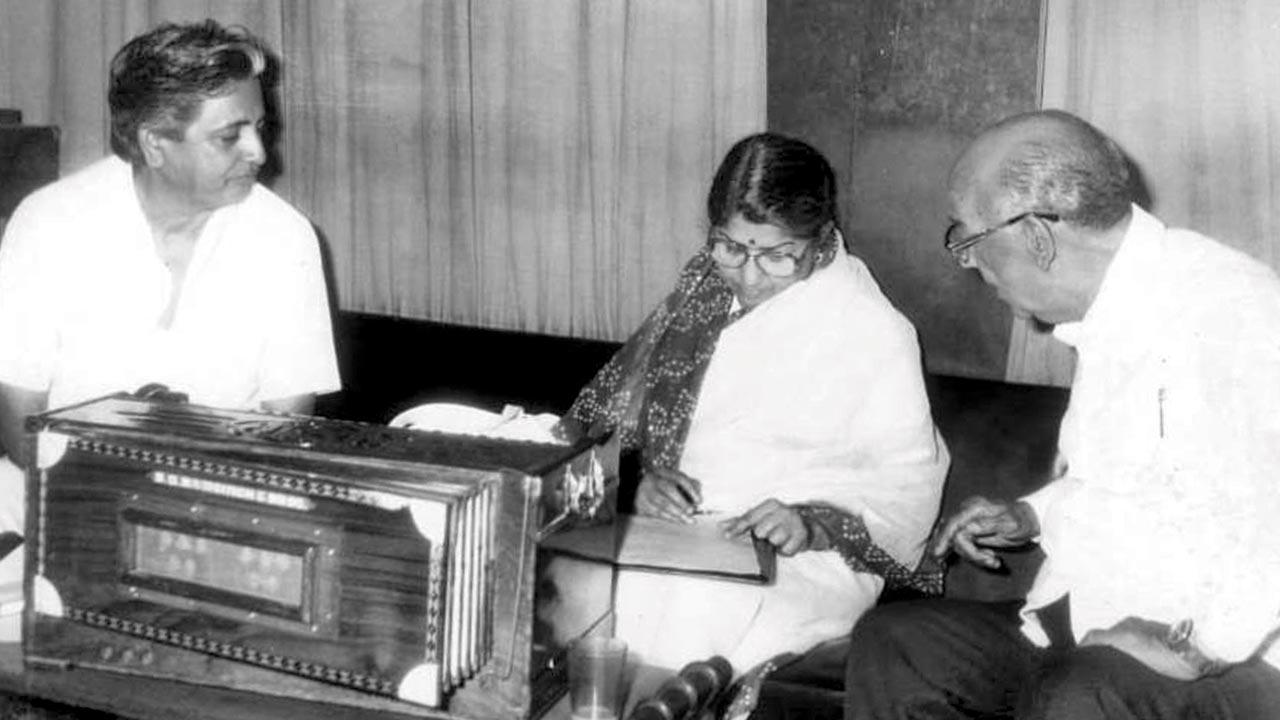

With Lata Mangeshkar and music director Ghanshyam

With Lata Mangeshkar and music director Ghanshyam

Reluctantly steered to the stability of a clerical job in the Simla municipal office till 1942, he knew his heart belonged elsewhere. To the elegantly cadenced Urdu nazms of Ehsan Danish. To the ghazals of Firaq Gorakhpuri. To the Hindi poems of Suryakant Tripathi “Nirala” and Sumitranandan Pant. He participated in poetry contests Delhi-Punjab publications announced in special supplements. Then, the prospect of writing for films tugged him to Bombay shores.

His first screenplay, for Janta in 1947, coincided with the foray as a lyricist for Zanjeer. In quick succession he worked on the script and lyrics of Aaj Ki Raat (1948) and conceived love songs of captivating charm, like “Chup chup khade ho, zaroor koi baat hain” (Badi Bahen, 1949).

Stills from Blackmail (“Pal pal dil ke paas tum rehti ho”) and Padosan (“Mere same waali khidki mein…”); With good friend music director Madan Mohan

Stills from Blackmail (“Pal pal dil ke paas tum rehti ho”) and Padosan (“Mere same waali khidki mein…”); With good friend music director Madan Mohan

Producers were soon flying him across the country to posh hotel rooms booked indefinitely. He wrote as and when he wished to, with incandescence of thought and luminosity of line. Doubtless, the itinerant lifestyle was rough on the family, especially for Krishan’s wife Savitri. “She managed the fort admirably, despite Dad away travelling most times,” says Bobby Duggal.

His personal picks from his father’s repertoire are the bhajan, “Sukh ke sab saathi, dukh mein na koi” (Gopi, 1970) and the tender lori, “Dheere se aaja ri ankhiyaan mein nindiyaan aaja ri aaja” (Albela, 1951) – “I sang my daughter Disha to sleep with this lullaby which has some sweet lines, ‘Jagtee hain ankhiyaan, sotee hain kismat’. Disha was born on Gokul Ashtami of 1996. The streets resounded with her grandfather’s song which blares each year that day —‘Govinda aala re aala’ (Bluff Master, 1963).”

Krishan’s trips multiplied once South India was equally smitten by his extraordinary talent. Assigned a Madras hotel room to write for SM Sriramulu Naidu’s Azaad in 1955, he asked the boy bringing him tea his name. It was Aplam. The result? “Aplam chaplam chap laayi re duniya ko chhod teri gully aayi re”.

The prolific graph peaked with AV Meiyappan Chettiar, who even offered him the prerogative of selecting the cast for AVM Productions from the 1960s. Actors vied madly for Krishan’s recommendations. The lyricist flouted the studio’s No Smoking rule, with a flunkey following him around with an ashtray to collect piled Gold Flake butts.

Satish Duggal says, “He wouldn’t struggle for words, nor resort to using complex similes. Simple observations sufficed. At a hill station in heavy rain, he gazed out from his hotel window. A lady appeared at hers in the opposite building. Seizing the moment, he scribbled: ‘Mere saamne waali khidki mein, ek chaand ka tukda rehta hai’ (Padosan, 1968).”

This ranks as one of musician Ehsaan Noorani’s top compositions by Krishan. “Actually, the entire Padosan album,” he votes. “Along with ‘Pal pal dil ke paas, tum rehti ho’” (Blackmail, 1973).

The Filmfare Award for “Tumhi mere mandir, tumhi meri puja” (Khandan, 1965), recognised Krishan as best lyricist, Ravi as best music director and Lata Mangeshkar as best female playback singer.

Unlike most of his peers, the industry’s highest paid songwriter had at least 75 films with writing credits. Besides Padosan, he wrote milestone movies such as Nagin, Pyar Kiye Jaa, Man-Mauji, Sadhu Aur Shaitaan and Bombay to Goa. The pen flew fast, with scant deliberation. Inspired, he scrawled lines on anything handy, restaurant bill, paper napkin, cigarette box or newspaper margin.

Working from the National Sports Club of India at Worli, he watched horses gallop to a finish on Mahalaxmi course. A familiar figure at the Poona and Bangalore races, he grabbed eyeballs when he won a R46 lakh jackpot at the 1971 Derby. Receiving the staggering amount with characteristic equanimity, he quietly walked out, unfazed by an army of waiting photographers going wild.

Granted a five-minute meeting with Indira Gandhi, on contributing part of the prize money to her PM Welfare Fund, he stayed much longer. “You must be happy winning the jackpot,” she remarked. “I am happier today to be with the Prime Minister of my country,” he replied. Against normal practice, a photograph was permitted, as she wanted one with him.

Sunil Dutt, Sadhana, RK Nayyar and Surinder Kapoor were among Krishan’s inner circle. One of his closest friends, Om Prakash, was also originally from Pakistan where he assumed the popular radio show avatar of Fateh Din. “Differences of opinion did not affect them,” says Satish Duggal. “As excited kids we looked forward to elders playing cards at Diwali. After an argument one night, my uncle and Om Prakash stopped talking to each other. Yet, professional dignity intact, he continued scoring songs for all Om Prakash’s films.”

Associated with music directors including C Ramchandra, Hemant Kumar, Ravi, Chiragupt, Salil Chowdhury, SD and RD Burman, Shankar-Jaikishen, Rajesh Roshan, Laxmikant-Pyarelal and Kalyanji-Anandji, Krishan had an exceptional friendship with Madan Mohan. He wrote him 284 songs, beginning with the music composer’s first hit, the foot-tapping “Ae dil mujhe bataa de” (Bhai Bhai, 1956). Describing their synergy, Krishan said, “Paanch-dus minute mein mukhda ho jaata tha aur phir sangeet bhi jald se taiyaar—hum nikat ke dost saath-saath aise kaam karte!”

Charismatic to the core, reaching for Black Label refills, he famously declared, “I was born not to slog but to enjoy life.” His nephew adds, “Always immaculately dressed, he had an aura, commanding respect without hankering for it. ‘My songs will speak for me and after me,’ he believed. The biggest stars would come running down from the crane to touch his feet.”

Introducing himself as “a poet for fun and a music fanatic who loves Rajinder Krishan”, Chandu Bardanwala in Jamnagar owns 1,400 recordings of his hero’s songs, 1,120 of them on video. “Mastering all genres, he preferred writing in Urdu rather than Hindi. So did Majrooh Sultanpuri, Hasrat Jaipuri, Shakeel Badayuni, Sahir Ludhianvi and Anand Bakshi. I consider 1949 to the early 1970s Rajinder Krishan’s heyday. But he was a very private person. I used to call him ‘invisible giant’.”

Bardanwala pairs his personal favourite lyrics Krishan wrote, teamed with iconic music directors.

With SD Burman:

“Aa gupchup gupchup pyaar kare, chhup chhup aankhen chaar kare” (Sazaa, 1951)

With C Ramchandra:

“Gore gore o baanke chore, kabhi meri gully aaya karo” (Samadhi, 1950) & “Yeh zindagi usiki hain, jo kisi ka ho gaya” (Anarkali, 1953)

With Chitragupt:

“Chal ud ja re panchhi, ki ab yeh desh hua begaana” (Bhabhi, 1957)

With Hemant Kumar:

“Mera dil yeh pukaare aaja” (Nagin, 1954) & “Chhup gaya koi re door se pukaar ke” (Champakali, 1957)

With Madan Mohan:

“Yun hasraton ke daag mohabbat mein dho liye” (Adalat, 1958)

With RD Burman:

“Kabhi kabhi aisa bhi toh hota hain zindagi mein” (Waris, 1969)

Rhyming to new riffs keeping pace with changing 1970s trends, Krishan matched the jaunty jazz of “Arre rafta-rafta dekho aankh meri ladi hain” (Kahani Kismat Ki, 1973) and rambunctiously upbeat “Mannu bhai motor chali pum pum pum” (Phool Khile Hain Gulshan Gulshan, 1978).

In a Vividh Bharati interview a little ahead of his death on September 23, 1987, he explained, “Har rang ki koshish ki hain maine–deshbhakti, samaajwadi, dharmic–chaahe woh Islamic ho ya Hindu [I have tried to incorporate every tone in my writings—patriotism, socialism, religion—be it Islam or Hinduism].”

Whatever the theme and tenor of his lyrics, Krishan consciously retained a certain integrity in his trajectory. Honouring a maxim that he stuck to with remarkable dignity lifelong—“Filmi gaane likhte-likhte kahi shaayari bhooli na jaaye.”

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at [email protected]/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!