Historically regarded as secondary, embroidery—like women’s roles—has been considered decorative. Surface, an ongoing exhibition by the Sutrakala Foundation in Jodhpur, elevates Indian embroideries from domestic craft to high art, redefining their conceptual depth

Aravalli II (2024), flanked by Aravalli I (2024), by Karishma Swali of the Chanakya School of Craft, is inspired by the Aravalli hills. These works blend hand-weaving, embroidery, and sculpture to honour the unspoken connections between Jodhpur’s land and its communities. Courtesy/Chanakya School Of Craft

Embroidery and surface decoration have long been dismissed as a “genteel hobby”—a passive, feminine pursuit tied to traditional roles of obedience and domesticity. Often relegated to tasks like mending clothes, adding decorative touches, or preparing a bride’s trousseau, embroidery was seldom recognised as a serious practice. This is, perhaps, a glaring reflection of the institutional bias in the art world.

Embroidery and surface decoration have long been dismissed as a “genteel hobby”—a passive, feminine pursuit tied to traditional roles of obedience and domesticity. Often relegated to tasks like mending clothes, adding decorative touches, or preparing a bride’s trousseau, embroidery was seldom recognised as a serious practice. This is, perhaps, a glaring reflection of the institutional bias in the art world.

ADVERTISEMENT

Yet, handcrafted textiles have always been central to social and trade networks. From royal embroideries like zardozi and aari, influenced by Persian and Central Asian styles, to temple hangings from Gujarat and Tamil Nadu, these creations symbolised power and prestige, crafted by men and backed by patronage.

Shell (2014) by Swati Kalsi in collaboration with Anu Kumari, Rupa Kumari, Poonam Kumari, Komal Kumari, Kajal Kumari, Neha Kumari, Asmita Kumari, Amrita Kumari, Shalu Kumari, Sudhira Devi, Anita Devi and Juli Kumari. Courtesy/Lekha Poddar and Devi Art Foundation

Shell (2014) by Swati Kalsi in collaboration with Anu Kumari, Rupa Kumari, Poonam Kumari, Komal Kumari, Kajal Kumari, Neha Kumari, Asmita Kumari, Amrita Kumari, Shalu Kumari, Sudhira Devi, Anita Devi and Juli Kumari. Courtesy/Lekha Poddar and Devi Art Foundation

Meanwhile, folk styles like Phulkari, kantha, Banjara, and Chikankari, passed down through generations of women, were expressions of personal creativity, often hidden from the spotlight. This divide—between “male” and “female,” between “professional” and “informal”—has long kept embroidery from receiving the exaltation it deserves.

The Sutrakala Foundation, a not-for-profit initiative by Shon Randhawa and Chand Balbir Singh, challenges the dismissal of female amateurism through its exhibition Surface, on view until February 23. Held In association with JDH, an urban regeneration project revitalising the Walled City of Jodhpur through design, technology, fashion, and culture, the exhibition spans three venues surrounding the historic Toorji ka Jhalra stepwell. It is nothing less than an anthology of inherited traditions and new artistic languages, delving into post-colonial Indian textile history, with each work standing independently.

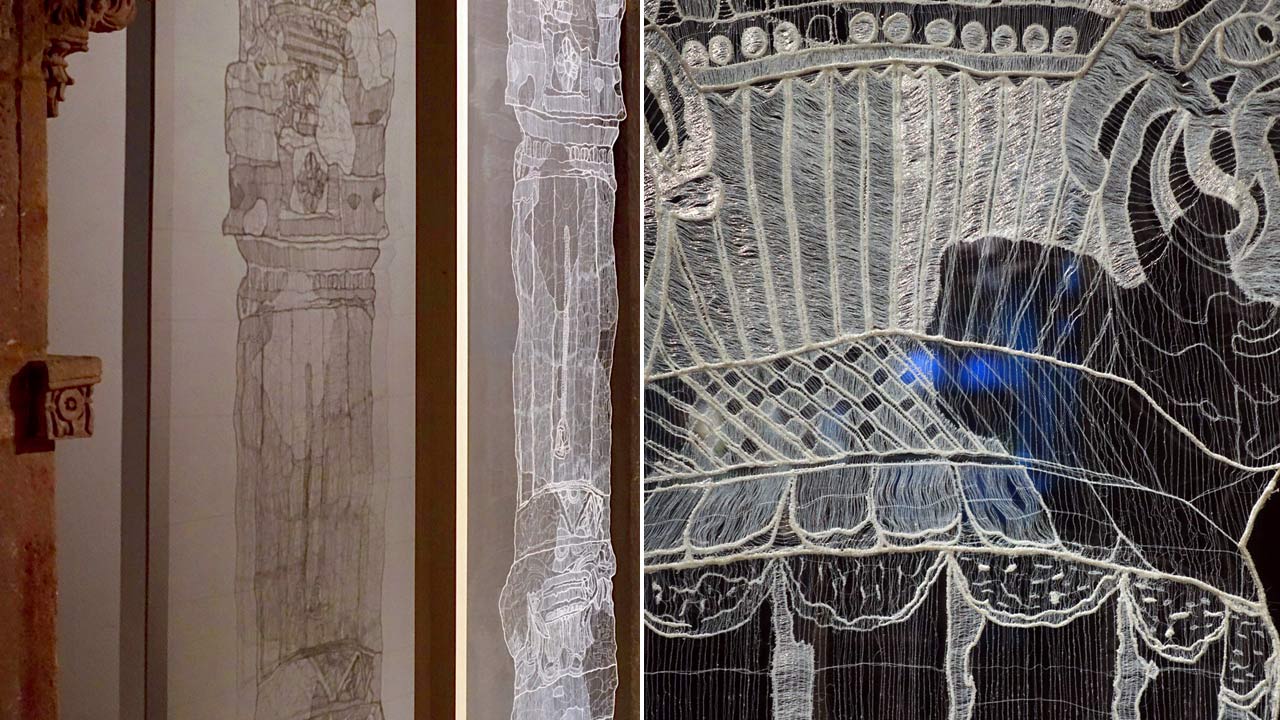

Surface as Structure: Monument to a Mirage (2024) by Sumakshi Singh in collaboration with Birendranth Sarkar, Bikas Burman, and Samarjeet Nirhankari. Courtesy/Exhibit 360

Surface as Structure: Monument to a Mirage (2024) by Sumakshi Singh in collaboration with Birendranth Sarkar, Bikas Burman, and Samarjeet Nirhankari. Courtesy/Exhibit 360

“I wanted to explore how Indian embroideries can go beyond their traditional roles in fashion, apparel, and home interiors,” says Randhawa, founder of fashion labels, Patine and Talitha. “It’s the possibilities… That’s what I find sexy.”

Curator Mayank Mansingh Kaul critiques the long-held, “misogynistic” belief that embroidery is merely “flimsy” decoration, often written off as something made by women for women. “The problem isn’t just who makes it,” he reasons. “At home, women embroider; in ateliers, men do it for women. The exhibition disrupts this view, presenting embroidery as a serious form of artistic expression.”

Swati Kalsi. (Pic Courtesy/Saurabh Behar); Sumakshi Singh; Karishma Swali

Swati Kalsi. (Pic Courtesy/Saurabh Behar); Sumakshi Singh; Karishma Swali

That the message is conveyed so subtly is what gives this exhibition its power—quietly telling a damning story through a stunning variety of subjects, styles and imagination. It brings together an intergenerational group of makers, including Bhujodi-based outfit Shrujan, Ahmedabad’s Asif Shaikh, Gandhinagar’s Morii Design by Brinda Dudhat, New Delhi’s Ashdeen Lilaowala, New York’s Ghiora Aharoni, Mumbai sculptor Parul Thacker and Chennai’s Jean Francois Lesage (Vastrakala).

Stitch by stitch, from delicate grids to monumental forms, the exhibition reimagines the “surface”, filling in its gaps and elevating the craft to the pedestal it has long deserved. Spanning materials—from silk faille and satin to cotton, wool, steel wires, and beetle wings—it ignites a sudden blaze of glory that transcends mere decoration.

Shon Randhawa & Mayank Mansingh Kaul

Shon Randhawa & Mayank Mansingh Kaul

Quite literally, as seen in veil-like architectural facades: tall columns that greet visitors as they ascend the steps of Achal Niwas. Gurgaon- and-Goa-based artist, Sumakshi Singh embeds fragments of embroidery into these skeletal structures, transforming them into monuments to memory. “A monument is meant to endure, preserving the ideology of its creator,” she says. “My work questions those ideologies. What are we building monuments to? Are they as fragile as a mirage, vulnerable to time and decay?”

Embroidery, Singh notes, is often viewed as an embellishment, never integral to the fabric’s structure. She likens this perception to how women have historically been seen: relegated to secondary, decorative roles. “Strong words, but I think it’s true,” says Singh.

Celestia by Mahua Lahiri (Hushnohana) in collaboration with Dibyendu Ghosh, Pampa Debnath, Priti Kana Goswami. Courtesy/Pritikana Women's Foundation

Celestia by Mahua Lahiri (Hushnohana) in collaboration with Dibyendu Ghosh, Pampa Debnath, Priti Kana Goswami. Courtesy/Pritikana Women's Foundation

Her process subverts this by embroidering onto soluble fabric. Once complete, the fabric dissolves, leaving only the thread as the core structure—transforming ornamentation into the very foundation of the piece. The figure becomes the ground, shifting the idea of what’s “essential” and what’s “decorative”—a reconfiguration that invites us to rethink social values.

Each room offers a distinct atmosphere, thoughtfully curated to create constant visual rhythm. One features the Alankar installation, inspired by the Mehrab motif from mosque walls and crafted from handspun cotton and various Chikankari stitches. These reinterpretations are designed by Chinar Farooqui of Injiri and created by artisans of Mijwan Welfare Society.

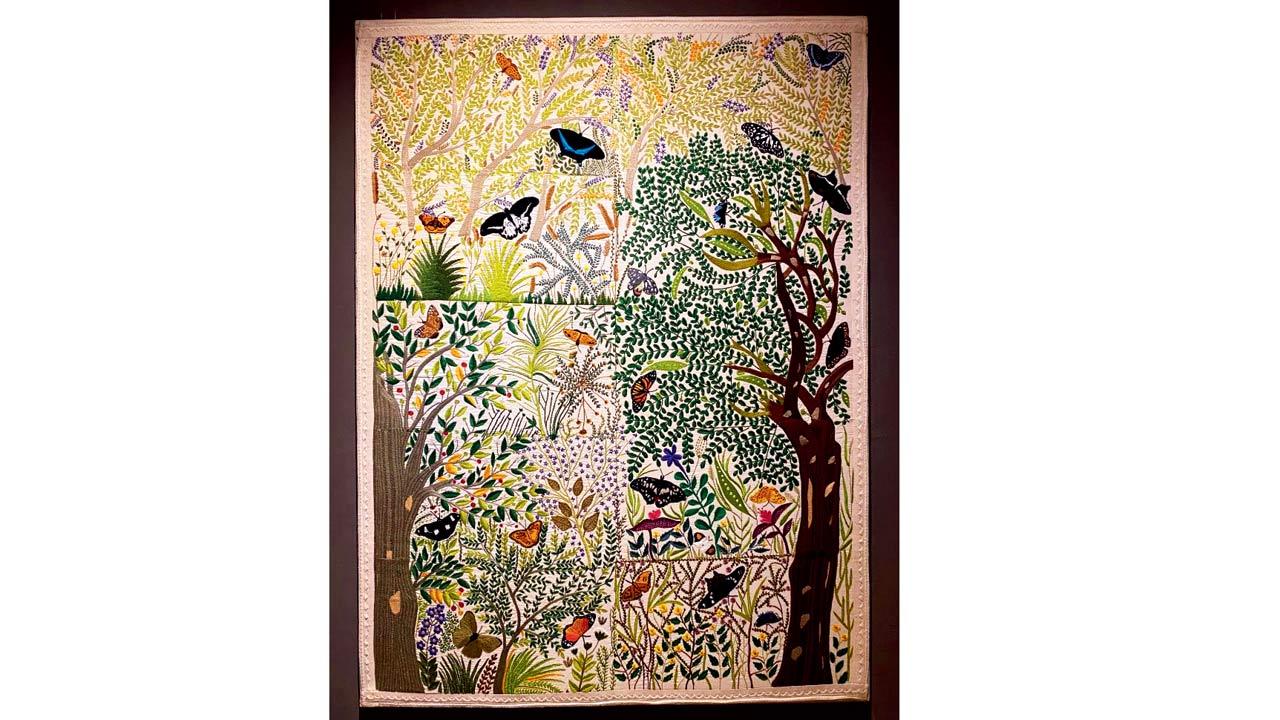

August in Sittilingi (2023-2024), presented by the Porgai Artisans Association at Surface, showcases the work of women from the Lambadi community in Sittilingi, Tamil Nadu. Created by Bhakialakshmi, Geetha, Kuppammal, Lavanya, Neela, Parimala, Selvi, Sumathi, Thaikulam, and Vanmathi, the textile evolves from workshops led by designer Anshu Arora and Dr Lalitha. Using traditional stitches, the artists reimagine familiar motifs into new narratives and landscapes. Courtesy/Porgai Artisans Association

August in Sittilingi (2023-2024), presented by the Porgai Artisans Association at Surface, showcases the work of women from the Lambadi community in Sittilingi, Tamil Nadu. Created by Bhakialakshmi, Geetha, Kuppammal, Lavanya, Neela, Parimala, Selvi, Sumathi, Thaikulam, and Vanmathi, the textile evolves from workshops led by designer Anshu Arora and Dr Lalitha. Using traditional stitches, the artists reimagine familiar motifs into new narratives and landscapes. Courtesy/Porgai Artisans Association

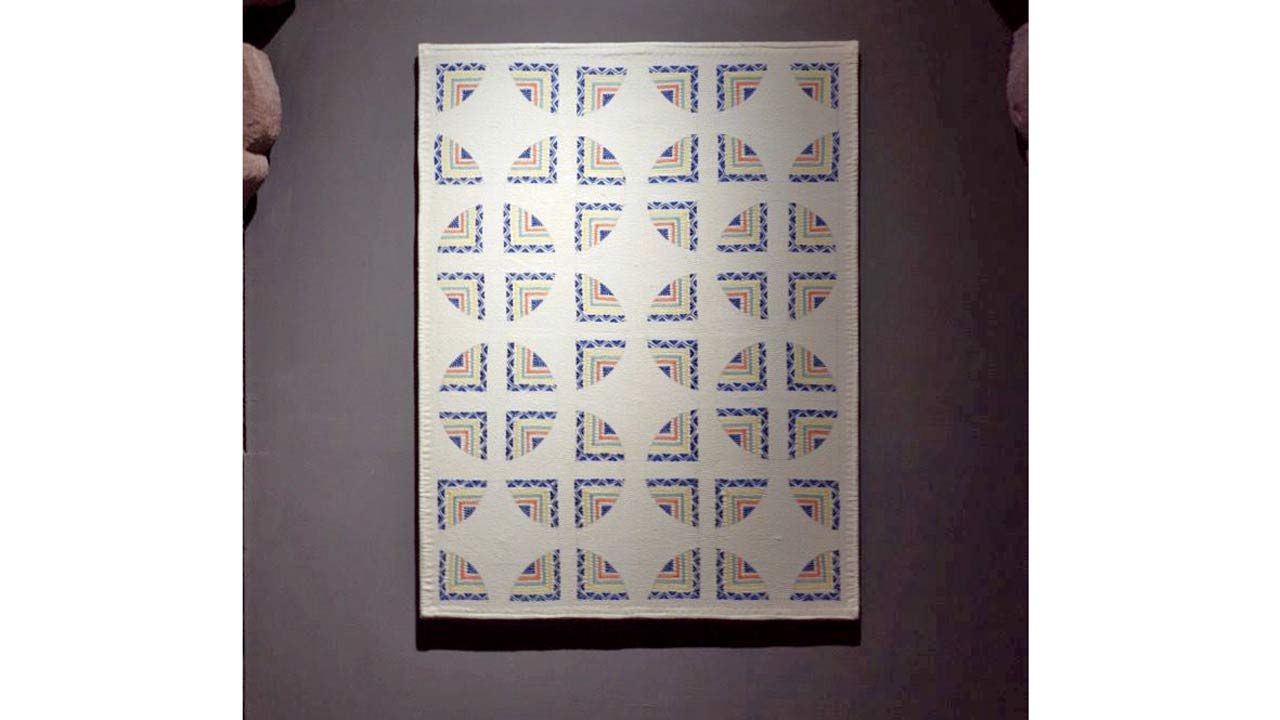

In Rippled Reverie and Celestia, designed by Mahua Lahiri and Priti Kana Goswami, sublime kantha from Kolkata is lavishly quilted in glowing hues, set against opalescent whites and creams. The works play on the romantic tendency of horizontals to evoke horizons—a common impulse in abstract painting—conjuring a beautiful impossibility of a never-ending mirage.

Sujani stitch, using cotton and zari threads, cascades from the surface, creating embroidery fireworks in Shell. “This piece took two years of ideation and creation,” says Swati Kalsi, who designed it. “For the first time, 12 Sujani artisans worked together on this large, labour-intensive work, part of The Fabric of India at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Each section is unique—no repeated motifs—flowing like a work of art.” Kalsi also presents eight other works exploring themes of modern weddings, nature, politics, and the celestial cow, using both Sujani and Chamba Rumal stitches.

Originally from Muzaffarpur and Bhusura in Bihar, Sujani evolved from simple stitches into vibrant geometric patterns, yet it remained rooted in domestic spaces. Kalsi, who began working with women’s embroidery in 2008, has helped shift its perception from subsistence work to an art form. “A hand has a brain of its own,” she says, believing that embroidery creates textures machines cannot.

To fully appreciate Aravalli II, one must look closely. Karishma Swali, creative director of the Chanakya School of Craft, intended the thread sculpture to embody a practitioner unconstrained by gender. “At its core, it’s about equity,” she explains. “We wanted to focus on the weave, form, and function rather than the identity of the maker.”

This philosophy aligns with Chanakya’s dual mission: to preserve India’s artisanal legacies while ensuring their future relevance, and to encourage women to master traditional crafts for both creative and financial independence. The Mumbai-based school, renowned for its fine embroidery, has trained over 1,000 women from low-income backgrounds in traditional techniques. Many have contributed to prestigious global collaborations, including with Christian Dior, blurring the lines between art, craft, textiles, and geography.

Swali sees embroidery as an ever-evolving medium of self-expression, much like painting or music. “Through the years, I’ve realised its infinite potential,” she says. “Embroidery thrives in community, and that, to me, is incredibly beautiful.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!