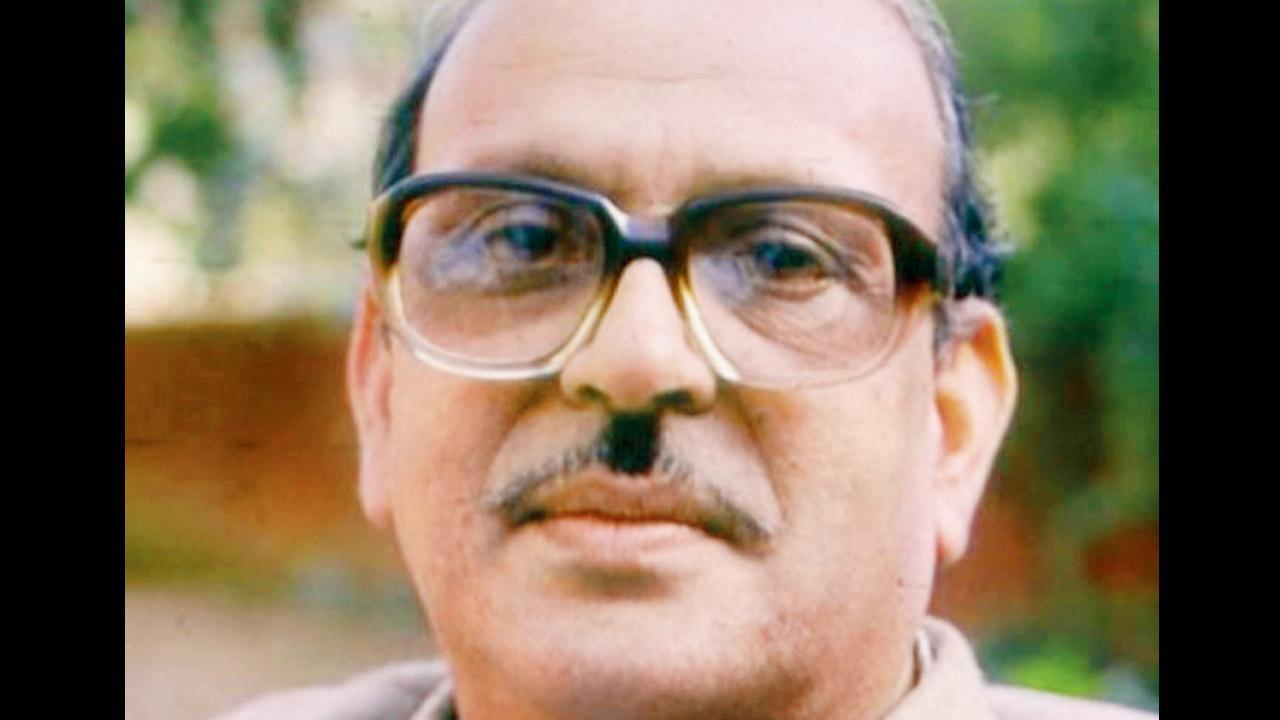

Of all the leaders who fought for the cause of OBC reservation but hegemonic discourses banished them into oblivion, no one deserves to be reclaimed more than the former prime minister

Former PM VP Singh had announced his decision on OBC reservations on August 7, 1990, which was, however, projected as a cynical manoeuvre against Dy PM Devi Lal

The emerging consolidation of the Other Backward Classes in Uttar Pradesh will likely continue regardless of whether the Samajwadi Party or the Bharatiya Janata Party wins the Assembly elections there. To give this process of consolidation a fresh impetus and ideological coherence, OBC leaders must now reclaim those leaders who fought for their cause but hegemonic discourses banished them into oblivion.

The emerging consolidation of the Other Backward Classes in Uttar Pradesh will likely continue regardless of whether the Samajwadi Party or the Bharatiya Janata Party wins the Assembly elections there. To give this process of consolidation a fresh impetus and ideological coherence, OBC leaders must now reclaim those leaders who fought for their cause but hegemonic discourses banished them into oblivion.

ADVERTISEMENT

No one deserves to be reclaimed more than VP Singh, who was prime minister between December 2, 1989 and November 10, 1990. His decision to implement the Mandal Commission’s recommendation for granting 27 per cent reservation to the OBCs in Union government jobs turned them, with due apology to Karl Marx, from “castes by themselves” into “castes for themselves.” This transformation presupposes social groups comprehending the mechanism of their own exploitation, which is what Uttar Pradesh is witnessing today.

Yet even OBC leaders seldom remember Singh, because of the backdrop to his decision on OBC reservation. Tired of then Deputy Prime Minister Devi Lal perpetually threatening to raise a banner of revolt, Singh dropped him from the Union Council of Ministers on August 1, 1990. An enraged Lal announced he would hold a rally on August 9, triggering fears that he planned to rally OBC MPs behind him to split the Janata Dal, the mainstay of the National Front coalition government.

Singh announced his decision on OBC reservation on August 7. This was projected, in the media narrative, as a cynical, spur-of-the-moment manoeuvre against Lal. Three decades later, Debashish Mukerji’s The Disruptor: How Vishwanath Pratap Singh Shook India, published late last year, puts out a chronology showing that the implementation of OBC reservation was always Singh’s project.

Three weeks after becoming prime minister, he appointed a committee under Lal to do preparatory work for implementing OBC reservation. But Lal was disinterested because his own community of Jats was not in the OBC list of the Mandal Commission.

In January 1990, PS Krishnan, a walking-talking encyclopaedia on the social justice movement, became the secretary of the Social Welfare Ministry. In an interview with Mukerji, Krishnan said that implementing the Mandal report was the “foremost” item on his “agenda of things to get done.” That would not have been possible without Singh’s consent. In March, then Social Welfare Minister Ram Vilas Paswan was handed over Lal’s brief.

On May 1, Krishnan prepared a note on the Mandal report for the Cabinet. While vetting it, then Cabinet Secretary Vinod Pande told Krishnan, “We have to find a way out of the Mandal problem for VP Singh.” Krishnan countered, “Problem?... VP Singh wants to enforce Mandal.” In May, Singh wrote letters to chief ministers seeking their opinion on the Mandal report.

Singh wanted to announce the decision on Independence Day, but Janata Dal leader Sharad Yadav advised it must be done before Lal’s rally on August 9. Krishnan’s note was presented to the Cabinet on August 2 for approval. Sure, Singh wished to use the Mandal report as a weapon against Lal, but its implementation was also advanced because of the parliamentary party meeting of the National Front on August 3.

At that rambunctious, four-hour meeting, Mukerji writes, an angry MP declared OBC reservation would never be implemented by upper caste prime ministers. Singh delineated the steps he had taken to implement the Mandal report. The MP retorted, “Bahaneybaji (Excuses).” Provoked, Singh asked the meeting to set a date for implementing the report. Thus was August 7 chosen.

Yet the media made a casteist presumption: Singh, a Rajput and an erstwhile royalty to boot, could not have had empathy for the OBCs, at the expense of his fellow upper castes, whose share in Union government jobs shrunk overnight. It is a testament to the power of hegemonic discourses that the elite’s narrative about Singh convinced OBC leaders as well.

It must be remembered that reservation before 1947, barring the Madras Presidency, was introduced in the princely states of Kolhapur, Mysore, Travancore and Cochin. Three out of these four princely states were ruled by Kshatriyas, the varna category to which, apart from VP, also belonged Arjun Singh, who was instrumental in introducing OBC reservation in higher education in 2006.

By inducting the two Singhs—VP and Arjun—into their pantheon of icons, OBC leaders could broaden their movement beyond caste, and turn it into a larger fight for equality, and equity. These twin quests were symbolised by VP Singh, who gifted over 200 acres to Vinoba Bhave’s Bhoodan movement. His government framed laws for establishing the Prasar Bharati and the National Commission for Women. Bureaucratic delays nixed his plan to pass a law on what we now know as the right to information.

In later years, Singh contributed his mite to the RTI movement, earning the admiration of Aruna Roy and Nikhil Dey, counted among the principal architects of the RTI Act. In their obituary on Singh, who died on November 27, 2008, they wrote that he would always be remembered for implementing OBC reservation. Yet it would be a grave injustice to him and posterity if “his role as a statesman politician in establishing the rights of the poor is not acknowledged.” Time for OBC leaders to write their own histories.

The writer is a senior journalist.

Send your feedback to [email protected]

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!