As the spirit of the season takes hold, there is soul-searching and celebration in equal measure. What stays overwhelmingly constant is an attitude of gratitude

Clockwise: Parsi thespians Burjor Patel, Dolly Dotiwala, Ruby Patel and Bomi Dotiwala in an NCPA rehearsal; the Once Upon a City celebratory cake they ordered

This column is blessed with a reach stretching unimaginably. Once Upon a City generates energies and synergies that beautifully knit people close. It keeps bringing me fresh learnings and appreciation, which validate the lengthy hours of research required.

This column is blessed with a reach stretching unimaginably. Once Upon a City generates energies and synergies that beautifully knit people close. It keeps bringing me fresh learnings and appreciation, which validate the lengthy hours of research required.

ADVERTISEMENT

Enveloped by abundant goodwill, I now have readers invite me over, asking when I plan to get to their lane, promising leads to people who will help navigate the vicinity. They add heft to every column, vaulting it further and deeper—making it more meaningful and most gratifying.

Reader reactions are especially welcome when they shed light on what I write as small slices of history. An exciting mail from five years ago proved to be as crucially revelatory as it was responsive: “I read with considerable interest your article on Forjett Street, Bombay. Charles Forjett (d.1890) is buried in Ladywell cemetery of SE London, England, and his headstone is one that is often referenced in guided walks of the cemetery.” Signed ‘Mike Guilfoyle, Vice-Chair: Friends of Brockley & Ladywell cemeteries’, this message importantly locates the tomb of the Anglo-Indian deputy commissioner of police (1856-64) who organised Mumbai’s first official force.

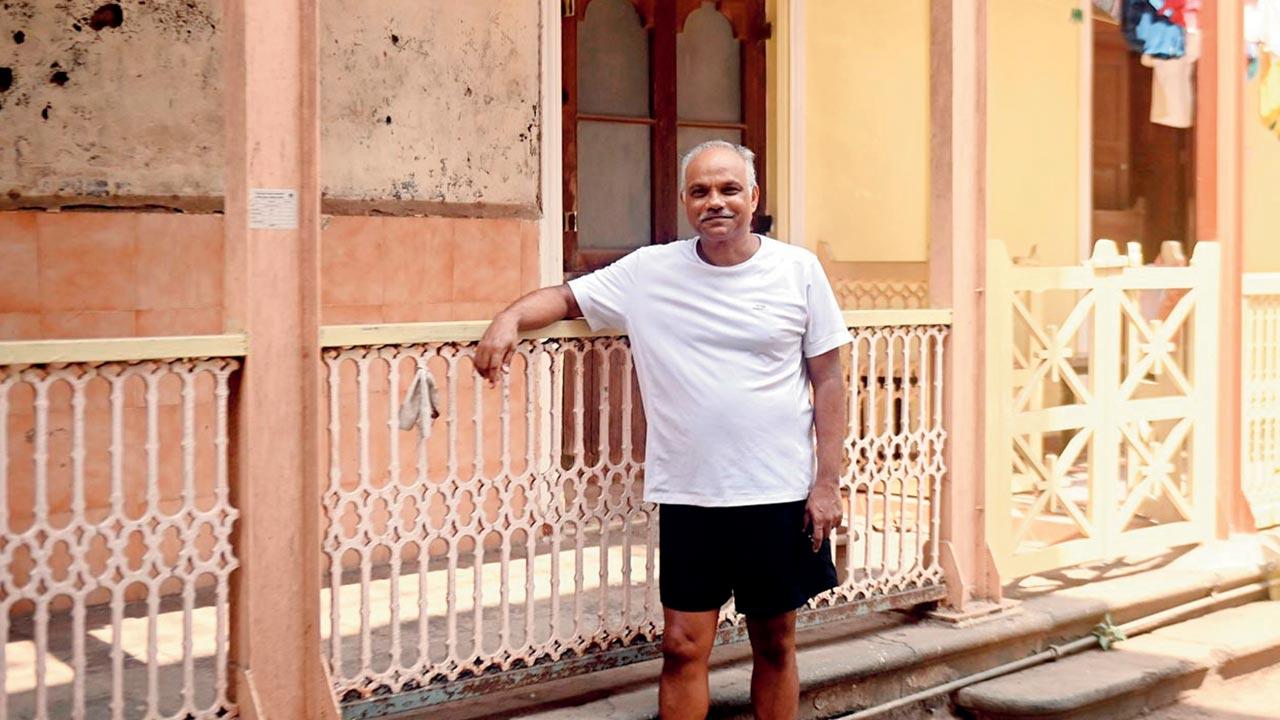

Filmmaker Hansal Mehta and his father Deepak at the site of their former bungalow Mukhi Nivas, in Khar three years ago. File pic

Filmmaker Hansal Mehta and his father Deepak at the site of their former bungalow Mukhi Nivas, in Khar three years ago. File pic

Slipping smartly into disguises, Forjett donned desi dress, spoke local lingo and artfully slunk through the shadows of dark streets to bust 19th-century crime rings. Forming effective night patrols, he rallied his men brilliantly. Volume 1 of the Bombay City Gazetteer notes: “His foresight and extraordinary knowledge of the vernacular saved Bombay from a mutiny of the garrison.”

Closer home, in the flood of weekly mail, I was glad to receive a warm communication from Hansal Mehta, unassumingly introducing himself after I wrote a 2017 column linking Khar’s past to its present. Politely complimenting the article, he offered his views on growing up in the leafy suburb, should I pursue a follow-up piece. I did, with delightful childhood vignettes from him. It was a stash of racy novels that unexpectedly spurred him on to make sensitive films such as Shahid, City Lights, Aligarh and Omerta. Narrating accounts of life in his former family bungalow, Mukhi Nivas, on 15th Road, Mehta said, “When I was housebound with a severe jaundice attack, kind Ifti Uncle (actor Iftikhar, Bollywood’s eternal cop and his father’s friend), three buildings away, sent over his entire James Hadley Chase collection to read. Those plots got me hooked to the idea of wanting to tell strong stories.”

Often, it is sheer chance that brings to light the affective impact of a story. It came as a happy surprise to hear how the captain steering an IndiGo flight on the

Vadodara to Mumbai route shared facts from the tribute to Maniben Nanavati printed on these pages on a Sunday in February last year. The parts the pilot focused on was her role as an educationist and tireless activist for the country’s freedom and women’s empowerment.

Julius Valladares at Keepsake, the Matharpacady cottage with typical Indo-Portuguese architectural elements. File pic

Some valuable insights on the beat come from the narrowest gullies. Like those of Dongri, for a piece that begged to be titled ‘Three cups of tea at Char Null’. It was here that three interviewees—a pair of Bhishti (water carrier) brothers, a charismatic surmawala and the presiding mujawar of the Baba Gor Sidi dargah—served me different cups of aromatic chai, each stirred in with a splendid story.

It was the man in the middle, Mohmmad Anis Shaikh, in his shop with the signboard ‘Dada Nanji Kamarsi Surmawala’, who gave me a second cup of mohalla chai, a tiny bottle of fragrant rose attar concocted on the spot, and an epiphanic moment of appreciating the worth of ancestry. His poet-turned-shopkeeper father, Gulam Nabi Taufiq, set up the store 10 years after arriving in 1920 from Navsari. Discovering that my paternal ancestors from the Meherji Rana family also claimed Navsari as hometown, he exclaimed, in a rush of Gujarati, Hindi and English, “We are both from Navsari but you’ve only been there once! I’m booking my train ticket to go next month. Let me add yours too.” When I demurred, he stressed, “Where we come from is everything. Tamey toh priestly class bhi, you’re from a priestly clan too. Our true roots lie in the mulk. This city just provides us roji-roti.” That was an unforgettable lesson in the distinct clarity of identity.

The columnist-as-conduit concept brings cheer and charm. Fresh from speaking to the living legend Ameen Sayani on the occasion of the Binaca Geetmala radio programme’s 70th anniversary, I happened to interview Cipla’s Yusuf Hamied for another piece. The two gents are firmly mutual admirers of each other. “Do take this from me to Ameen Saab,” Dr Hamied requested. In the pouch for me to pass on to Sayani was Unforgettable Melodies, a three-hour disc compilation of songs from films by Hamied’s father-in-law, AR Kardar. The actor-producer from Lahore launched mega stars, including Chand Usmani, Naushad and Majrooh Sultanpuri, and gave Mohamed Rafi his early hit, Suhaani Raat Dhal Chuki.

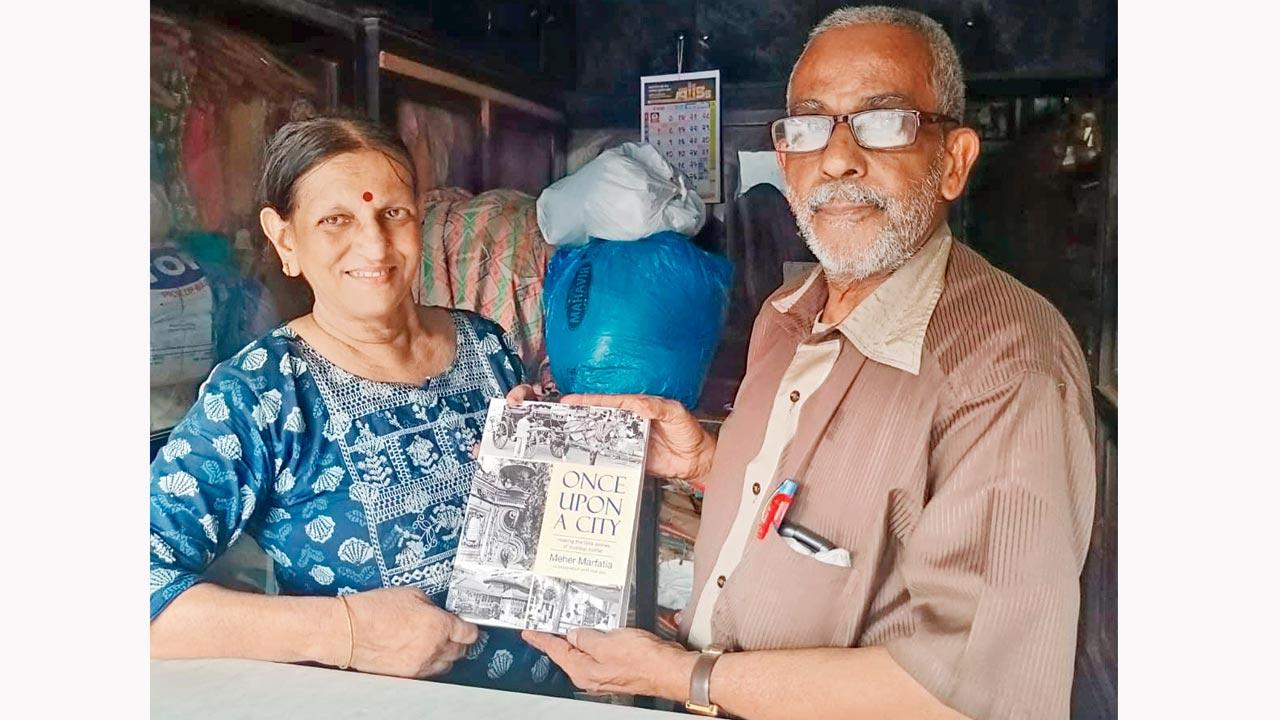

Savitri and Mohandas Kamath at the 1936-established Orient Cleaners, King’s Circle. Pic/Sujata Rao

Savitri and Mohandas Kamath at the 1936-established Orient Cleaners, King’s Circle. Pic/Sujata Rao

Objects hold emotions, becoming repositories of the significance we attach to them. Sipping copious amounts of chai daylong, I treasure a lovely little blue and white coaster given by Phorum Pandya, who edited the forerunner to this column—a fortnightly half-page called Urban Legend. What she picked in an old Middle Eastern souk, I associate with an overall sense of wellbeing. Whether it is battling writer’s block before looming deadlines, or feeling under the weather, or dealing with personal ebb and flow, the three-inch diameter of this ceramic roundel seldom fails to soothe. The comforting sight of it, followed by the sound of any mug clink lightly down on its surface, quite adequately reassures, restores, reboots.

One of the sweetest gestures of encouragement has been the Once Upon a City cake. It was ordered backstage before a performance of Laughter in the House, the play born of my book on Parsi theatre of the same name. April 12 was a day of multiple celebrations, it being actress Ruby Patel’s birthday, also her wedding anniversary with producer-actor husband Burjor, besides being director Sam Kerawalla’s birthday. If a show was performed on or around that date, there was inevitably a mithai box to open, a cake to cut. Yet, there they were, acknowledging my book, smiling, singing, clapping and hugging as I sliced wedges of chocolate.

In a world increasingly pocked by untruth and disinformation, the voice on the street emerges authentic. Exploring vibrant King’s Circle, I lucked out at Orient Cleaners. Pulled in by the vintage typography lettering advertising the name of this laundry, I was soon astounded by the ease with which Mohandas Kamath at the counter could reel off engrossing anecdotes tracing the Circle’s socio-cultural fabric in the last century. Long live the Kamaths of the world, keepers of the secrets the city hides within. They make wonderful raconteurs, engaging in talk beyond gully gupshup, describing their neighbourhoods with passion in accurate, animated detail. His, to me, were the gifts of time and thought. In turn, he proudly posed with a copy of my Bombay book delivered to him.

The ordinary are ever extraordinary. The inhabitants of Matharpacady in Mazagaon have never lacked faith and hope—qualities being severely tested in the ongoing fight against ruthless redevelopment threatening the 16th-century settlement of their forebears. Two Christmas evenings ago, when other East Indian villages sparkled with stars and fairy lights, residents of this gaothan mindfully donated for COVID relief the money to otherwise be spent on lighting. They created their own brightness. From buttercup yellow-painted Keepsake, seaman Julius Valladares has a friendly wave for all who walk slowly past, admiring this 1928-built house’s exquisite woodwork. He is known to generously usher total strangers into the candle-lit cottage for Christmas sweets. A Shakespeare buff, his mother christened her sons after Julius Caesar and Mark Antony.

A quote from 50 years ago continues to inspire. I found it while profiling the maverick architect-politician Piloo Mody. His idealism tempered with realism drew him to the liberal Swatantra Party, headed by C Rajagopalachari. Pertinent Piloo-isms ring chillingly relevant amid today’s hyper-jingoist rants. Condemning caste in 1973, he said in March of the Nation: “It’s disgraceful enough if looking down on human beings was confined to keeping out of their way or barring them entry into temples. What cannot be countenanced is bigotry erupting in vicious cruelty, connived at by society, condoned by the authorities.” But the words by him that I find best to believe in are—“The world revolves around an idea. Every problem has its solution, given a clean heart, good intention and determination.”

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at [email protected]/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!