Could you continue to learn something new about India’s longest serving public figure, still? Surely!

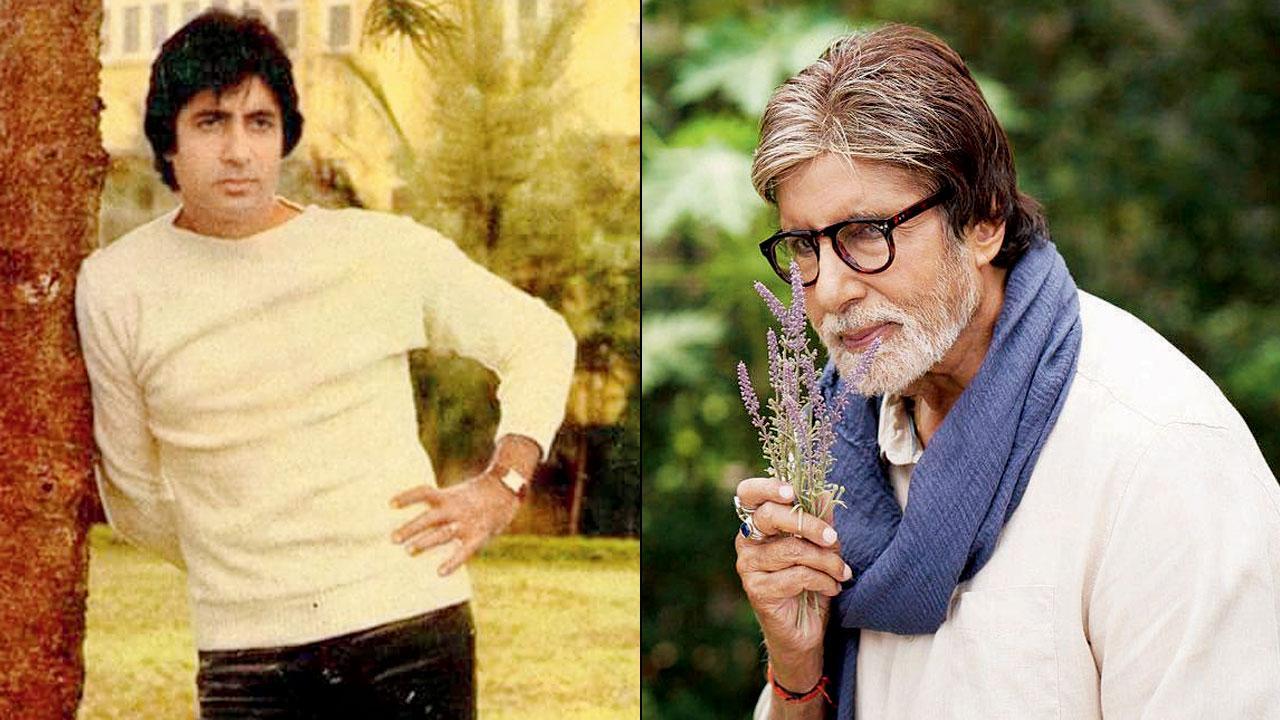

Salim-Javed’s script Zanjeer (1973) brought Amitabh Bachchan irreplaceable stardom, and there has been no looking back since. Pics/Twitter

Superstar Amitabh Bachchan’s contemporaries alone comprise nearly half of Hindi cinema’s history. So, it’s only fair that everyone, vintage apart, has a Bachchan (Big B) story to tell.

Superstar Amitabh Bachchan’s contemporaries alone comprise nearly half of Hindi cinema’s history. So, it’s only fair that everyone, vintage apart, has a Bachchan (Big B) story to tell.

ADVERTISEMENT

For instance, super-villain Prem Chopra, 87, told me from his relative youth—working with Bachchan and Shashi Kapoor in Yash Chopra’s Trishul (1978)—when they’d have early morning shoots, but could party all night, regardless. Little before call-time, when they should’ve attempted a power-nap, Chopra recalls, Bachchan would bring over his sitar and regale them with his impromptu performance. We know Bachchan as a legit playback singer, starting with Mr Natwarlal (1979).

He also composes music, we learnt, because that’s what he did for director R Balki, to express his thoughts after watching his film Chup (2022). That Big B composition, on piano, plays in Chup’s end-credits!

How did Bachchan become a professional actor? Well, comedian-filmmaker Mehmood and his brother Anwar Ali were his early mentors, yes. Mehmood’s Bombay to Goa (1972) showed off Big B’s skills as an entertainer. Ali brothers regularly recommended him for roles.

For the story before that, I discovered a book—Legends of Bollywood by one Raaj Grover. Grover was a close confidante of Sunil Dutt, who had sent him over to meet Bachchan in Calcutta, where he worked as a freight executive in Bird & Co. All this happened, because Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had called up Nargis Dutt. They were friends. So were Mrs Gandhi and Bachchan’s mother, Teji.

According to Grover, entrusted with chaperoning Bachchan for five days—for which he’d come down to Bombay on leave from work in Calcutta, Big B screen-tested for B R Chopra at producer Mohan Segal’s set. Nothing came of it. Bachchan had earlier entered the Filmfare-Madhuri talent hunt. No luck there either.

Dutt, of course, did give Bachchan a part in his ensemble film, Reshma Aur Shera (1971)—where Big B, later loved for a ‘rich baritone’, played a mute character!

To be fair, the first time Big B’s name appeared on a film credit was for his voice-over in Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome (1969). The credited name was ‘Amit’—Amitabh was seen as too long.

During Rehma Aur Shera’s shoot, Big B and actor Ranjeet, who became a stock villain in the ’70s, were roommates. He recalls his first memory of Bachchan as a quiet, young man, who never skipped his prayers, and letters to his parents.

How did he land his first role though, in K A Abbas’s Saat Hindustani (1969)?

Then aspiring actor-director Tinnu Anand says he was supposed to play that part. Since Tinnu had dropped out of catering college, his father, legendary writer Inder Raj Anand, suggested the son assist Fellini or Satyajit Ray instead. Inder knew both. As per Tinnu, Fellini’s crew wouldn’t be familiar with English, so he sought an appointment and began working with Ray! Hence Bachchan got his acting debut.

Salim-Javed’s script Zanjeer (1973) brought him irreplaceable stardom. Thereafter, there could be weeks with eight Big B releases simultaneously playing in theatres.

The superstar, right before Bachchan, was Rajesh Khanna—notorious for arriving late on set, causing heart-burn and holes in producers’ pockets.

Big B’s professionalism, in contrast, got defined by his punctuality first. Ranjeet says this is also because workaholic Bachchan sleeps very few hours. One can’t deny his undiminished hunger/ambition; seldom resting on his past feat.

Take an instance actor Naseeruddin Shah cited to me about a script with three male leads. During the writing process, as each lead got stronger, better defined, one superstar decided to pull off all three!

While Naseer never mentioned Bachchan, I’m pretty sure the film is Mahaan (1983).

As a journalist, of course, I have too many Big B stories. From drawing out a headline—‘Feels like my mother is no more’—with a leading question, when his onscreen mom Nirupa Roy passed away, to having him urge Iraqi militia to release Indian truckers held captive off Baghdad—those terrorists were self-confessed Big B fans. He’s a sport!

There are signed letters of appreciation framed or lying in the drawers of countless film talents in Bombay, when their work has been noticed by Big B. He just does it naturally, including never failing to wish colleagues (even their children) on their birthdays.

My second favourite Big B anecdote (best is saved for future), relates to a ‘letter to editor’ in mid-day, about a fracas at 2003 Zee film awards in Dubai. A gentleman from Borivli accused Big B of being a “media creation”, who mustn’t deem “ordinary people” as lesser beings—just because he was asked to be seated in the seventh row at the award show.

Big B e-mailed a 1,000-word piece, asking me to pass it on to the Borivli resident. He countered the first point, saying his greatest years as a superstar (mid ’70s onwards) were when the media had banned him—so much for being its creation. And that he felt everyone was extraordinary (or ordinary), for that matter.

This is before Big B began blogging. Floored by the quality of the piece, I asked, “Would you pen a regular column? You write so well.” He replied, “Not as well as you!” My jaw dropped, and has been on the floor since. This is how you win the world with grace and charm.

Mayank Shekhar attempts to make sense of mass culture. He tweets @mayankw14

Send your feedback to [email protected]

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!