What’s it about Bollywood’s own, late ’90s Boogie Nights, that makes us think about movies differently

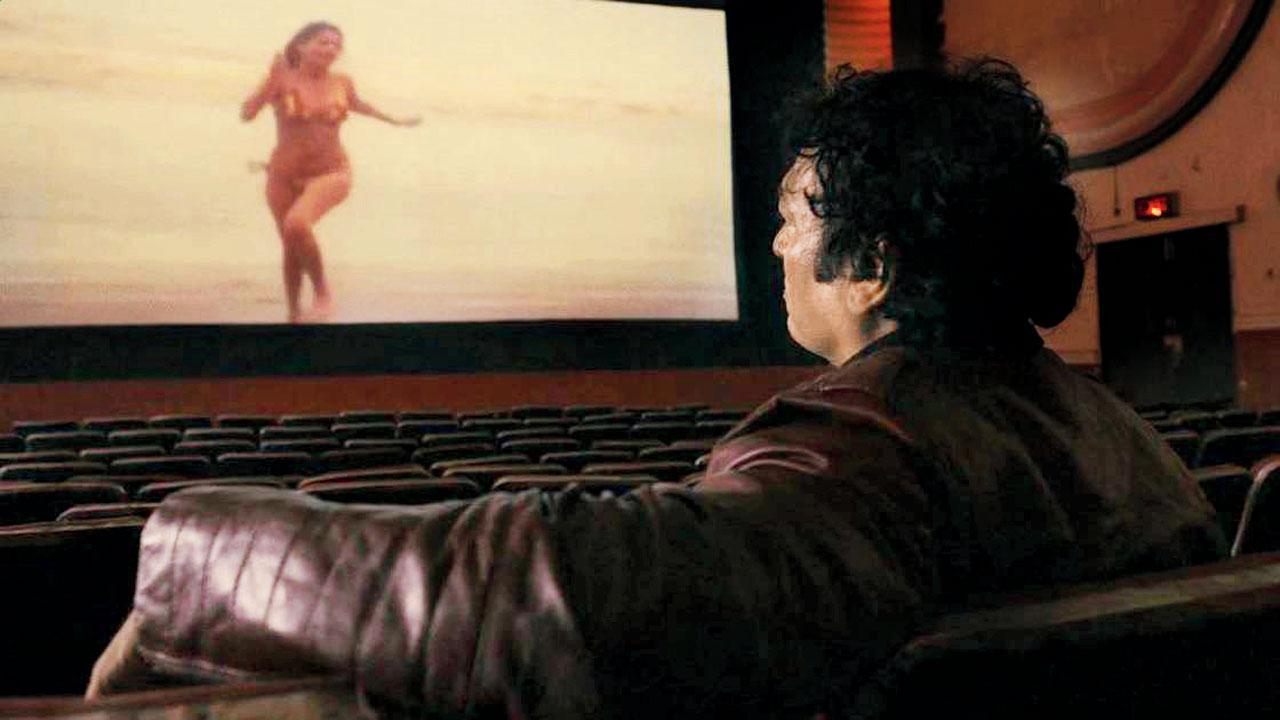

A still from Cinema Marte Dum Tak

The opening shot of Vasan Bala’s docu-series Cinema Marte Dum Tak (CMDT), on Amazon Prime Video, is a scene from Kanti Shah Ke Angoor, starring superstar Sapna. It’s the same moment, I think, that also referentially features in Vikramaditya Motwane’s Udaan (2010).

The opening shot of Vasan Bala’s docu-series Cinema Marte Dum Tak (CMDT), on Amazon Prime Video, is a scene from Kanti Shah Ke Angoor, starring superstar Sapna. It’s the same moment, I think, that also referentially features in Vikramaditya Motwane’s Udaan (2010).

ADVERTISEMENT

CMDT is a nod to Bollywood’s B/C-grade cinema, which peaked in the late ’90s. That makes the opening shot, unrelated to scenes that immediately follow, a tribute of a tribute, of a tribute—an inception of homage, if you may.

Motwane was also a “talking head” in CMDT, but his appearance got edited out. In Udaan’s script, there’s mention of how students sneak out of boarding school, to watch a “naughty film”. The writer-director, therefore, had to explore the said naughty-picture genre, in order to arrive at what movie the kids will watch, for a film, within the film. Hence: Kanti Shah Ke Angoor.

That Motwane, in his early 30s then, hadn’t sampled any of the said C-grade pictures earlier, I’m guessing, is that old desi lie—common among those much younger, who had seen all these random pictures, with posters on walls, often smeared in black paint, and titles with double meanings, that could only have one meaning, after all.

Vasan Bala

Vasan Bala

It’s only with social media that audiences (mostly boys), who’d naturally come of age with this seedy cinema, began to connect, like besotted fans. And Kanti Shah’s Gunda, for instance, acquired a shared cult following of sorts—“a cue to find your tribe.”

How do you define these movies? Bala rightly points out that B/C-grade is an Indian term—in line with the desi obsession of hierarchically placing people into suitable boxes. B-movie, on the other hand, he says, came from Hollywood, as an industry standard.

Meaning, studio films that starred top-notch, popular stars were the A-movies, of course. The B-movies featured actors who were on the studio’s payroll headlining a lower-budget production. This double-bill subsidised potential losses too. B-movie, being the Plan B.

Indeed, over time, B-movie actors graduated to A-movies as well. Take John Wayne, for instance? While many didn’t, say, Ronald Reagan—although he eventually elevated himself to the highest form of acting of them all, i.e. politics; as the US President, no less.

Hindi cinema has its parallels in the stunt plus ‘sword & sandal’ space, isn’t it? This is where Dara Singh would be the loved Baadshah of B-movies, in the ’60s; Mumtaz, his heroine. Dharmendra probably occupied the A-movie equivalent of the same genre later.

At some point in the sunset of his career—perhaps because he needed money, was plain bored, or just dying to be on set—you could spot superstar Dharmendra in a bunch of what could be categorised as “pulpy, terribly awesome, quickies”, including those directed by Kanti Shah, undisputed Sardar of Bollywood’s C-grade trade.

What marked these late ’90s, early noughties’ “naughty films” as separate from the past? Often, this thing called the “bits”—basically pornographic scenes inserted for random segues. This cinema was the distributor’s medium. He financed the picture, basis title and poster. He progressively demanded more “bits”, to a point that there was no picture left.

Greed is no good. Many slipped on a banana peel. For CMDT, Bala’s team got in touch with about 50 directors from the time. Many didn’t wish to be identified, or face the camera, for fear of their past returning to haunt them. Why did these guys disappear into irrelevance, at all? Hello—Internet!

That said, Kanti allegedly morphed Dharmendra riding a horse, in a scene, into him riding a woman instead, in one of his films. That was the end of Kanti, apparently. But that’s not why he became big.

Also Read: I haven’t had a cold since 2019

What Kanti introduced to C-grade cinema was the audacity of hope. That he could recruit Dharmendra at all, besides the great Mithun Chakraborty (‘Prabhujee’, in social-media circles), or the likes of Kiran Kumar, Raza Murad and others, is a big deal, isn’t it?

He offered stars, cash, per diem, in advance, for a shoot that would last about a couple of days or so. Also, he was the master-tailor at stitching sourced footage from big-budget films into his low-key enterprise—matching wide shots with close-ups for stunts, car-chases, the works.

I met Kanti at the prestigious Golden Kela Awards in Delhi, circa 2010. I’d flown down especially to receive the ‘worst movie critic’ prize—what an honour. Kanti was being felicitated for ‘lifetime achievement’. Proud of bagging the Kela, Kanti was all praise about himself, along with his heroine, Sapna, on stage—‘sarchasm’ is that needless space between intended sarcasm and the one who doesn’t wanna get it.

That footage is there in CMDT. The docu-series features the return of four retirees—directors Dilip Gulati, J Neelam, Vinod Talwar and Kanti’s brother, Kishen Shah—making their comeback short films, Jungle Girl, Shanti Basera, Blood Suckers and Sautan Badi Chudail.

As the show’s creator, Bala—Anurag Kashyap’s protege, who’s made the critically acclaimed Mard Ko Dard Nahi Hota (2018) and Monica, O My Darling (2022)—says, these directors essentially aren’t slaves to their filmmaking circumstances.

Like them, he’s also been “trained not to curtail ambition, and to find truth within the frame”. What’s the difference between him and them still, I ask Bala. “Aesthetics, and gaze,” that’s it.

Mayank Shekhar attempts to make sense of mass culture. He tweets @mayankw14

Send your feedback to [email protected]

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!