Why does it take you hours to find anything but a Google search can pull out what you want in nanoseconds? Can we learn their hacks?

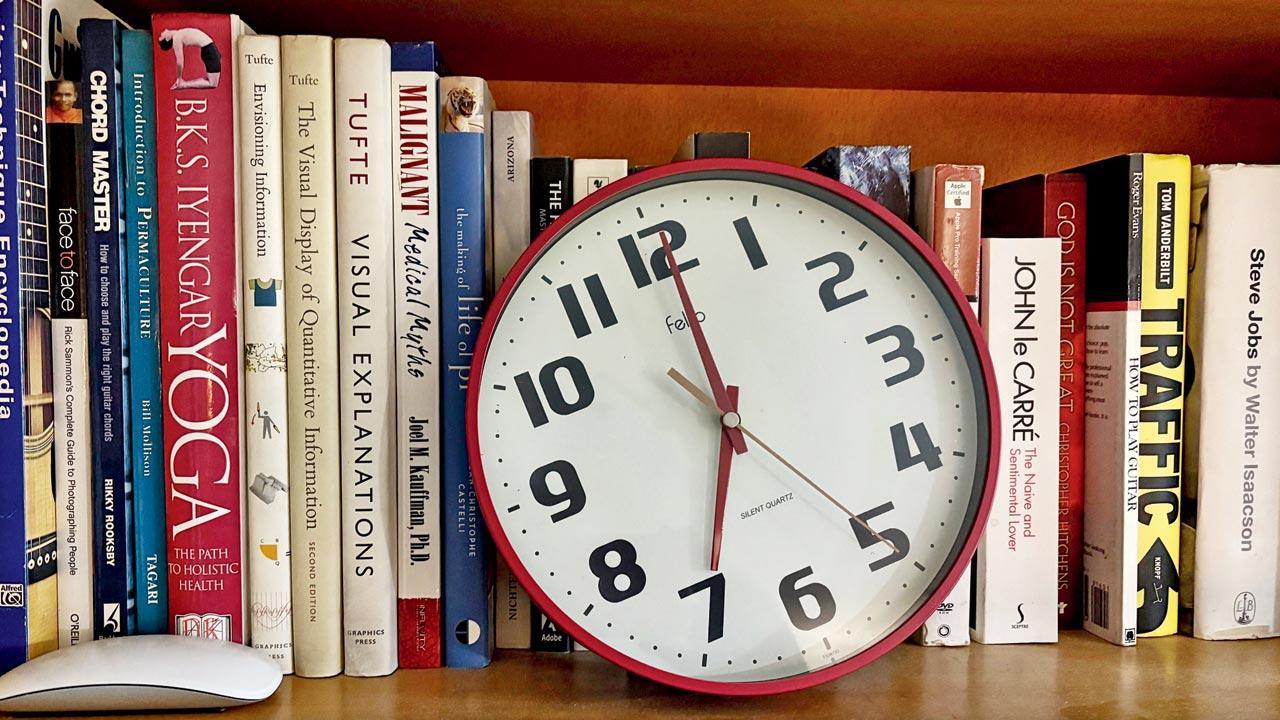

Behind my work desk is a rack with 191 books, reflecting the befuddled polymath who owns them. Photo by C Y Gopinath

Ramu the Bamu left a mess behind when he passed in 2017. As his brother, it fell to me to sort through the prodigious debris of his life, mostly books, magazines and sundry files and papers. Ramu, beloved to all who knew him, was accepted for what he was: the absent-minded, kindly lord of his pigpen. He lived in a room defined by its chaos, where he and only he could accurately and swiftly find whatever he wanted.

Ramu the Bamu left a mess behind when he passed in 2017. As his brother, it fell to me to sort through the prodigious debris of his life, mostly books, magazines and sundry files and papers. Ramu, beloved to all who knew him, was accepted for what he was: the absent-minded, kindly lord of his pigpen. He lived in a room defined by its chaos, where he and only he could accurately and swiftly find whatever he wanted.

ADVERTISEMENT

Covering an entire wall in another room were his nearly 3,000 books and magazines from a lifetime of squirrelling: Punch, Geo, National Geographic, LIFE, Playboy, Penthouse, New Yorker, Esquire, in the magazine half, and weathered and brown collections of books from the Jurassic Era in the other half.

If you wanted, say, for Playboy’s interview with Truman Capote, Ramu the Bamu could fish it out instantly.

I have far fewer books. My cuisine shelf has 125 books on food and cooking. In the guest room are 61 books mainly related to diet, health, cholesterol, photography and, idiosyncratically, tips on how a gentleman should dress. Alone on a single shelf are 19 battered Tarzan books. Behind my work desk is a rack with 191 books, reflecting the befuddled polymath who owns them.

But earlier today, the polymath could not find a specific book—Hatter’s Castle by A J Cronin—in this meagre collection of 306 books, even after turning the shelves upside down and inside out. It took hours.

It takes your wife ages to find the soont powder in a swarm of 50 or so spice bottles. You search for a particular tie among your dozens, you just saw it last week, where could it have gone?

Made me wonder about Google search. I ask a question—say, Why isn’t the sky green?—and even before my fingers can rise from the Return key, Google is already displaying the top 10 of about 1,510,000,000 results, compiled in apparently 0.34 seconds.

Almost as good, I’d say, as Ramu the Bamu.

Could we speed up how quickly we find our spices, books, ties and files by studying how Google does it?

In 1975, Intel’s Mr Gordon Moore correctly predicted that computing power would double every two years. It did, but the universe of stored knowledge has also been exploding. The more information a storage device has, the longer it takes to search through it. A better solution was needed.

So they invented a cache, a special, super-fast memory module for keeping information you accessed recently or frequently. A bit like keeping a few much-needed textbooks handy as you study.

By the way, your mother and her mother before her knew all about caches; so probably does whoever cooks in your home. India’s most ubiquitous cache is the masala dabba, the circular, lidded steel container with six canisters for storing powdered dhania, jeera and mirchi, as well as whole jeera, mustard and pepper—the most commonly accessed spices of the Indian kitchen.

This masala dabba has another feature: it is right next to the cooking area.

Google and other websites understand the importance of proximity. When data flashes by at the speed of light, reducing the distance between the server and you revs up the delivery. If you’re in Mumbai, your search results are not coming from the Googleplex in Mountain View, California, but probably from a content delivery network in Marol or Nallasopara.

Let’s say you’re a quick study, and this column has inspired you to create a small ‘cache’ closet for clothes you wear regularly and a larger one for less frequently used attire like business suits.

What will you do when your closet gets full?

A computer would evict some data to create space. But how does it decide which items to evict from an overloaded cache? In computers, the first to go would be the Least Recently Used (LRU) items.

Sounds geeky, but humans have been using LRU in their daily lives long before computers. For example, I have made several hundred friends over my life but I divide them now into those with whom I have regular contact, and the ones who are in my address book but not my life. They are my LRU friends, who only send me cat videos and Janmashtami greetings now and then and don’t even expect a reply.

LRU is powerful. Facebook has used it to subvert minds and democracies. Their algorithm assumes you want more of whatever you watched recently. If it was a climate change conspiracy video, your feed would fill up with more climate-paranoid videos. Pretty soon, you’d be a raging conspiracy theorist who trusts nothing and no one.

Today, I rearranged my books, banishing the LRUs. I began parking frequently accessed books on a shelf away from the LRUs. Recently-read books go to the left side of that shelf. It’s a new life, and it’s weightless.

Try it, it’s easy.

1. Separate the LRUs from your collections so that your most recently accessed books, clothes, spices, whatever, are within easy reach and the rest are elsewhere.

2. After using any of them, place them back on the very left of the storage space.

Seek now, and ye shall definitely find.

You can reach C Y Gopinath at [email protected]

Send your feedback to [email protected]

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!