How do you observe loss of a man whose career was older than his nation? Through history, not obituary!

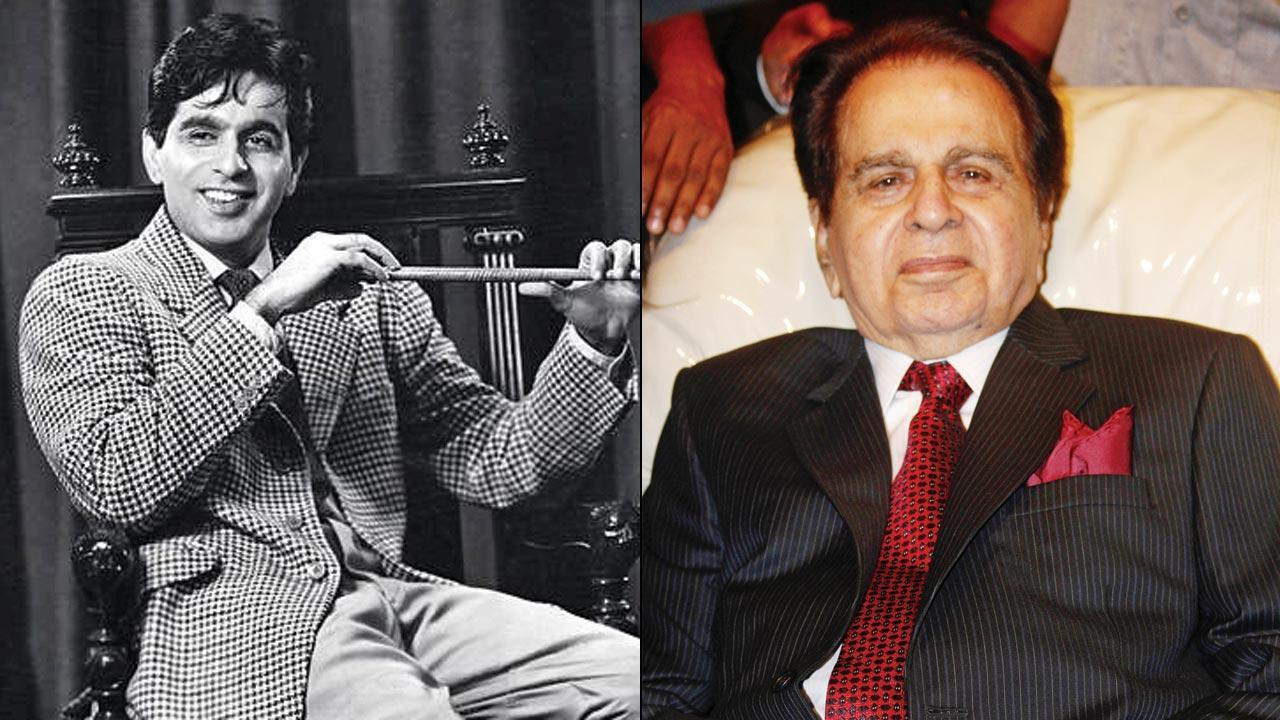

Dilip Kumar

How old is the agile Prime Minister of entire Indian government (currently)? 70. How old was the last one (at end of term)? 81. What’s the retirement age for an Indian bureaucrat? 60. Used to be 58, until 1998. What about Supreme Court judge? 65. High Court? 62. The latter sometimes get accused of doling out favours for post-retirement jobs. Can’t expect them to sit idly at home either, no?

ADVERTISEMENT

Sarkari age limits are probably based on estimates from independence, when India’s average life expectancy itself was 31 years! 1947 is also when actor Dilip Kumar (nee Yusuf Khan), 25, got his first major commercial success as actor—starring opposite Noor Jehan, in Jugnu, directed-produced by Shaukat Rizvi.

Before this, Dilip Kumar had been hired by Devika Rani’s Malad-based Bombay Talkies to debut in Jwar Bhata (1944). Bombay Talkies, being a traditional studio, rolling out multiple productions in a year, meant everyone (from star to spot-boy) would draw a corporate salary. There were many such.

The studio system collapsed during WWII, chiefly for hyper-inflation and restriction on imports (of film raw-stock). The star-system replaced it. Meaning, an independent producer or freelance moneybag could hire talents for a film—basis a popular lead actor saying yes to it. Hero’s face on poster drew audiences in. Dilip Kumar was that big face in the ’50s. He also worked in fewer films. He was his own boss, and could charge a fee he thought fit.

Dilip Kumar worked on his last movie, still as lead, in 1998, with Qila. He was 76. By early 2000s, when I saw him first in Bombay (as a journalist), rambling on in a speech (perhaps Alzheimer’s setting in), the audience around me was simply in a state of ecstasy/awe—looking at a living piece of eternal nostalgia, talking in suit and boot.

For several decades, Dilip Kumar had comfortably slipped into journalistic cliché of a ‘thespian’, not (any other) actor. Same way superstars of ’50s (Dilip, Dev Anand, Raj Kapoor), like Khans (Aamir, Salman, Shah Rukh) of ’90s, are always ‘triumvirate’; never a trio. Amitabh Bachchan’s voice = ‘baritone’. Saab is similarly Gulzar’s last name. As was Dilip’s.

Dilip Saab passed away on July 7, 2021. I’ve gobbled every piece that I could lay my fingers on him since. Barring a sobering eulogy, where fellow actor Naseeruddin Shah calls a spade a Dilip Kumar, lamenting all the more the superstar could’ve done for cinema, but didn’t—most others seemed to me an exercise in genuine, honest, intellectual adulation for the man who lived, rather than an instinctive/emotional outburst over a man we lost.

This isn’t surprising. If you consider that artistes/stars from pop-culture we identify with most spiritedly/viscerally, are those we grew up on (teenage idols is top of the pop)—hardly those we grow old with. Of course Dilip Saab’s greatest works survive still. Yet, for many writers, Dilip Kumar was from a time before theirs. Sure he made a comeback in the ’80s too—Shakti, Vidhaata, Mashaal, Karma.

But the stellar years he got credited with literally inventing understated calmness, and confident pause, on the big screen—and what it must’ve done to first-time audiences in theatres—happened in ’50s, and ’60s: Devdas, Ganga Jamuna, Madhumati, Aan, Kohinoor, even Andaaz (1949).

Besides that he regretted turning down three films—Deewar (1975), being one of them (Pyaasa, Baiju Bawra, the other two), my favourite Dilip Saab story is from Mihir Bose’s book, Bollywood: A History. BR Chopra sacked Madhubala from the Dilip Kumar starrer Naya Daur, because of her father’s interference. Chopra published an ad in a film-trade paper, showing Madhubala’s name crossed out from Naya Daur; replaced by Vijyanthimala.

Madhubala (evidently at father’s behest), in turn, ran an ad showing her upcoming films—crossing out Naya Daur from it. Law suit and counter suit followed, with crowds gathered outside a magistrate court in Girgaum, where Dilip Saab was brought in as key witnesses in a ‘breach of contract’ case.

What did Dilip Kumar do in court that fired up the press next morning? Confessed his love for Madhubala, before the judge! To explain breach of contract, since disapproving father wouldn’t allow couple to shoot outdoors.

That’s literally a ‘Pyar kiya toh darna kiya’ moment from his own Mughal-e-Azam in (or, well, before) Naya Daur. It’s from the mid ’50s, when Dilip Saab would’ve been in his early to mid 30s.

In the years he’d seen off British India, lived during Jawaharlal Nehru as India’s PM—for whom he was also a face for multiple public causes—down to Narendra Modi as PM (2014 onwards), Dilip Kumar remained also a poised/charming symbol for a syncretic culture, also public activism (including film industry issues), when occasion demanded.

It’s only when you sit through old pieces/videos/encomiums from his past, from peers and purported protégés alike (SRK literally rolling down the red carpet for him at an award show), you realise the beauty of the rarest long life, where one needn’t depend on posthumous tribute to rekindle intense public admiration.

He found it, all through—and knew how to take a compliment (like greats do). Maybe that’s how he lived till 98. Century would’ve been perfect for the cricket fan.

Mayank Shekhar attempts to make sense of mass culture. He tweets @mayankw14

Send your feedback to [email protected]

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!