As 2025 approaches, makers from the Himalayas and North East region reclaim the stage, weaving new meanings into India’s cultural fabric, while honouring the stories of its land and people

Namza Couture’s HOR-LAM collection, set in Basgo—a village along the Indus River in Ladakh—celebrates the deep connection between land and textile traditions. Pics Courtesy/Avani Rai

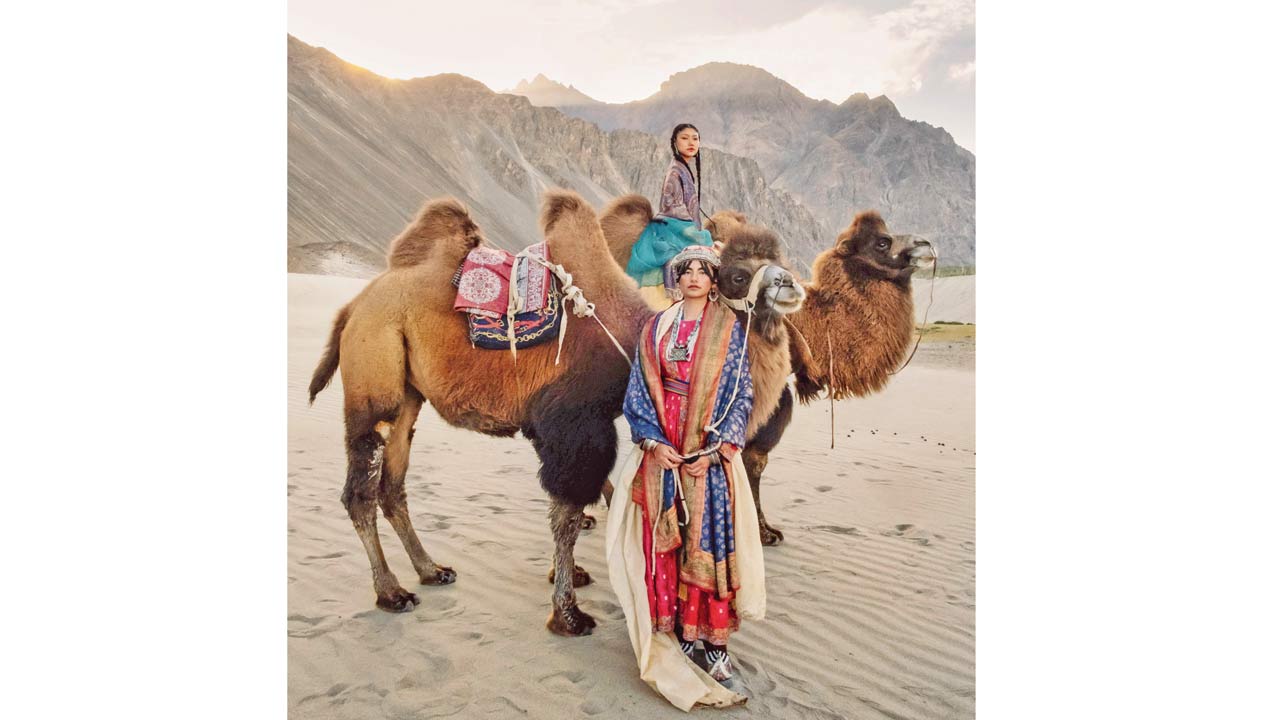

Model Anika Bogi stands, hands folded, gaze fixed, against a double-humped camel, dressed in a Ladakhi Sulma. With its elongated lines and voluminous silhouette, the robe evokes ritual. Designed to fall into a gown, it gathers (sul) at the waist with knee-length slits for ease of movement. Crafted from wool, brocade, velvet, or silk, it is secured at the waist with a brightly coloured skeyrak (sash) and paired with a tilin blouse, its wide sleeves rolled up in warmer weather. Traditionally worn by Ladakhi women, the Sulma often signifies marital status.

Model Anika Bogi stands, hands folded, gaze fixed, against a double-humped camel, dressed in a Ladakhi Sulma. With its elongated lines and voluminous silhouette, the robe evokes ritual. Designed to fall into a gown, it gathers (sul) at the waist with knee-length slits for ease of movement. Crafted from wool, brocade, velvet, or silk, it is secured at the waist with a brightly coloured skeyrak (sash) and paired with a tilin blouse, its wide sleeves rolled up in warmer weather. Traditionally worn by Ladakhi women, the Sulma often signifies marital status.

ADVERTISEMENT

In another photograph, Mila Dechen wears a Mogo, a traditional Ladakhi dress layered with a Bok—a wool shawl with vibrant colours and intricate patterns, reflecting Ladakh’s textile heritage. It’s paired with a gyaser, a silk brocade woven with gold and silver zari on wooden pit looms in Banaras.

Namza Couture collection, captured amidst the sand dunes of Ladakh

Namza Couture collection, captured amidst the sand dunes of Ladakh

Avani Rai’s photographs form a chiaroscuro hymn to Namza Couture’s HOR-LAM collection—named after the Route of the Hor People. “Hor” refers to the Uyghur “Horpa” communities from Xinjiang, and “Lam” means route. This ancient term connects to Ladakh’s role as a crossroads on the legendary Silk Road, linking Kashmir to the west, Tibet to the east, and Yarkand in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region to the north.

Through these poetic images, Padma Yangchan, the brand’s co-founder and designer, brings the ancestral Ladakhi textiles into conversation with contemporary design. “Ladakh’s textiles are shaped by its high-altitude environment and historic role as a Silk Road junction,” says Yangchan. “The fine quality Ladakhi pashmina is produced by goats adapted to the harsh climate. Other traditions include gyaser weaving, tigma dyeing, and yak wool weaving, each rich in cultural symbolism and storytelling. These crafts not only distinguish Ladakh’s textile history but also add to the diverse fabric of India’s craft legacy.”

Padma Yangchan, co-founder and designer of Namza Couture

Padma Yangchan, co-founder and designer of Namza Couture

Woven into Aratrik Dev Varman and Jisha Unnikrishnan’s textile installation is the Risha, a narrow, handwoven breastcloth traditionally worn by women of Tripura’s 19 tribes until the 1970s. This installation shifts focus from the finished textile to its creation process, drawing inspiration from the simplicity of the backstrap loom. Using just a few bamboo sticks to set up the warp, this lightweight and portable loom was essential for tribes practicing shifting agriculture, moving between hills to cultivate crops. Held by the weaver’s body, the loom limits the width of the textile, giving the Risha its characteristic narrow form of about 20 inches.

Measuring 3 feet by 14.5 feet, the installation is framed in teak wood, with cotton and lurex yarn woven into its multi-striped composition. Two sets of intersecting threads create a play of opacities, referencing Tripura’s tribal textiles. “We wanted the focus to remain on the loin loom’s simplicity,” says Varman, who hails from Tripura and now runs his label, Tilla, in Ahmedabad. “It’s not just about the object, but about the story it tells: the tools, the craftsperson’s life, and the context behind the tradition,” Varman adds.

Jagrity Phukan, founder and creative director of Way of Living Studio

Jagrity Phukan, founder and creative director of Way of Living Studio

Similarly, in Arunachal Pradesh, Jenjum Gadi looks at the loin loom, a tool used by his community for centuries, attached to the weaver’s body with a back strap. “It’s the first loom in history, its process unchanged, embodying the essence of slow fashion—unhurried, deliberate,” says Gadi, a contemporary designer from Tirbin village now based in New Delhi.

“Instead of creating fashion for fashion’s sake, textiles are a powerful way to raise awareness of my community’s heritage,” Gadi explains. “While it may seem homogeneous to outsiders, each state—from Nagaland to Arunachal Pradesh—has its own distinct craft language.”

Aratrik Dev Varman and Jisha Unnikrishnan with The Tripura Project, an installation commissioned by Royal Enfield Social Mission. Pic Courtesy/Tilla by Aratrik Dev Varman

Aratrik Dev Varman and Jisha Unnikrishnan with The Tripura Project, an installation commissioned by Royal Enfield Social Mission. Pic Courtesy/Tilla by Aratrik Dev Varman

For his latest menswear collection, Gadi draws inspiration from the Mopin festival, an agricultural celebration of the Galo tribe dedicated to the goddess Mopin Ane. Traditional Mopin attire features bold black-and-white geometric patterns, which Gadi reinterprets in black garments adorned with white motifs, giving ancestral symbolism a modern twist.

Rather than viewing indigenous crafts as static traditions, Yangchan, Varman, Unnikrishnan, and Gadi treat weaving as a living art form, evolving through its intersection with contemporary design across Ladakh, Tripura, and Arunachal Pradesh.

Aratrik Dev Varman (right) and Jisha Unnikrishnan

As 2024 draws to a close, craft enters a golden age of cultural storytelling, where the ancestral skills of textile artisans meet distinctly urban design approaches. This revival of interest has brought fresh attention to Himalayan and North East textiles.

Festivals like Journeying Across the Himalayas, held earlier this month in New Delhi, have spotlighted over 50 Himalayan communities and their artists across art, music, photography, food, design, and architecture. This diversity of works, makers, and meanings underscores culture’s power to shape identity—through its many forms, it remains one of the most accessible and enduring expressions of who we are. “The festival was founded on the recognition that the Himalayas hold stories worth sharing and preserving. As the region faces the impacts of climate change, it highlights the resilience of its communities, inviting a broader audience to celebrate their legacies,” says Bidisha Dey, executive director at Eicher Group Foundation, which organised the festival.

From Folk to Fabric: The Himalayan Knot exhibition in New Delhi recently explored textiles, folktales, and material culture across nine Himalayan regions

From Folk to Fabric: The Himalayan Knot exhibition in New Delhi recently explored textiles, folktales, and material culture across nine Himalayan regions

Part of this effort was the From Folk to Fabric exhibition, part of The Himalayan Knot project, which brought together nine Himalayan communities to share their stories. “The project inspires us with how craftsmanship connects diverse Himalayan communities. At Royal Enfield, craftsmanship is at our core, from hand-painted pinstripes to our attention to detail. The project celebrates the region’s textiles and traditions while supporting communities, promoting sustainable crafts, and preserving living heritage,” explains Dey.

Curated by Ikshit Pande, and contributions from Dr Monisha Ahmed (Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh), The Woolknitters (Himachal Pradesh), Anand Joshi (Uttarakhand), Aagor (Assam), Easternlight Zimik (Manipur), Charlee Mathlena (Mizoram), Kevisedenuo Margaret Zinyü (Nagaland) and Sonam Tashi Gyaltsen (Sikkim), the installations presented a layered narrative of not just textiles, but folktales and cultural memory.

Bidisha Dey, executive director, Eicher Group Foundation

Bidisha Dey, executive director, Eicher Group Foundation

For all the detail and sophistication in design, textiles remain living documents of the land, communicating shared ideas through folktales, myths, and oral histories. “Interest in heritage textiles, particularly from regions like Kutch and Bengal, has always been strong due to their accessibility,” observes Pande. “Now, textiles from the plains are starting to attract attention, but often through a limited lens—either by patrons or in museums. Modern storytelling by the original custodians is key to broader engagement; without their voices, these materials risk becoming forgotten relics.”

The exhibition transcended notions of luxury and the exotic, beginning with the Pawnpui—a traditional Mizo cotton blanket, valued as a bridal heirloom—and extending to the Moon shawl, a testament to Kashmiri weaving artistry. “Textile traditions from the eastern and western Himalayas are integral to India’s craft landscape, particularly in preserving intangible cultural practices and promoting sustainability. From natural dyes in Bodo cotton to sustainable Eri silk techniques, these textiles connect communities to their environment,” Dey says.

Jenjum Gadi’s latest menswear range draws inspiration from the black-and-white motifs found in the folk stories of the Galo community

Jenjum Gadi’s latest menswear range draws inspiration from the black-and-white motifs found in the folk stories of the Galo community

Each textile, whether designed by a contemporary artist or woven by an artisan, represents the transference of ancestral knowledge, evolving over time. This dynamic interplay gives textiles their “human face,” illustrating their ongoing relevance across generations. “They are more than just skills,” Pande reasons. “They pass down stories, beliefs, and traditions, with each piece reflecting the maker’s moods, experiences, and the communal nature of the craft.”

Some of the most inspiring stories from the Himalayan and North East regions come from communities where conservation and culture intersect. Green Hub, founded by Rita Banerji, empowers young people through visual storytelling focused on social change and conservation. Since 2015, Green Hub has partnered with grassroots organisations to support sustainable practices and amplify local voices.

Jenjum Gadi, menswear designer

Jenjum Gadi, menswear designer

The North East region, home to about 3.6 per cent of India’s 1.4 billion population, faces high unemployment and environmental challenges. The Green Hub Fellowship provides a platform for young changemakers, and the Green Hub Royal Enfield Conservation Grants—introduced in 2022—have supported youth from over 20 communities across six states in North-East India.

Wanmai Konyak of Nagaland is restoring jhum lands, while Chajo Lowang and Sara Khongsai from Arunachal Pradesh are documenting biodiversity and folktales from Tirap, and launching a conservation project. In 2024, Rangjalu Basumatary received a grant for his work protecting the Bengal Florican in Manas, and Jagrity Phukan was awarded for her Soil to Silk project, preserving Muga silk traditions in Dhemaji, Assam.

“Muga silks are the embodiment of slow fashion—like denim, they become more comfortable and durable over time,” Phukan explains. Since class 9, Phukan had dreamed of a career in fashion. After graduating from NIFT and working with the Ganga Maki brand, she felt drawn back to her village in the foothills of the Himalayas. There, inspired by her grandmother’s muga silk weaving, she launched Way of Living Studio (WOLS), reviving the craft while weaving in sustainable, modern values.

“Nature and the indigenous communities of Dhemaji are central to everything we do,” says Phukan, acknowledging how parts of her region feel overlooked by mainland India. “People sometimes don’t know where I’m from because of my Mongolian features. There’s a lack of awareness, but indigenous communities have always been part of this country—people just need to pay attention.”

This disconnect is something Yangchan also grapples with in her work. “The term ‘regional’ oversimplifies the depth and cultural significance of Himalayan crafts,” she argues. “When people say ‘it’s too regional,’ I ask them, ‘What about Chikankari or Phulkari? Aren’t those regional too?’ Every craft, from the Himalayas to the plains, carries its own unique story and legacy, deserving of respect and global recognition.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!