Who will write about India’s handloom revivalists? Well, they themselves. Hema Shroff Patel rummages through mood diaries, memories and Maheshwar’s textile weaving milestones for a just-launched book that’s unusually personal

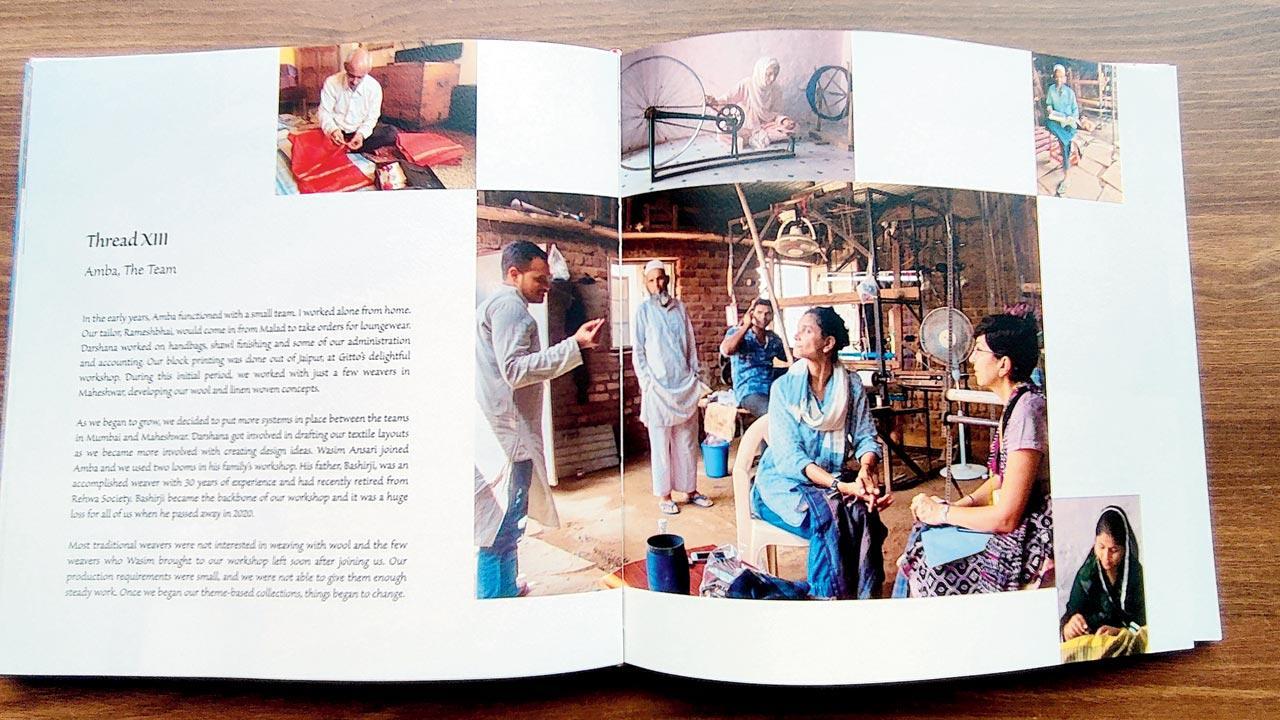

Hema Shroff Patel (centre in blue) seen in discussion with weavers from team Amba. Pics Courtesy/Amba Twenty-one Threads

When Suman Chauhan settles in for the day’s work at 11 am, dropping her legs into the cavity of the pit loom to position her feet on pedals and tells me, “Yahan mistake nahin chalti”, she is paying a compliment to her senior colleague; a quality control manager who sits a courtyard away from her in a tiny room lit by a bright tube. He carefully rolls out an aubergine-edged red Maheshwari cotton-silk saree in rhythmic spurts over a wooden rod that hangs on a swing of sorts, running his gaze from behind his spectacles, left to right, in search of an error. It’s the final stage of quality check conducted at a unit of Rehwa Society’s weaving centre in the ramparts of Ahilya Fort in Maheshwar, Madhya Pradesh’s temple town famed as much for the Narmada river that licks the flagstones of its ghats as its hand-weaving tradition, that some say, dates back to the 5th century.

ADVERTISEMENT

At this non-profit weaver’s cooperative, which employs local men and women, the fight to live up to a legacy is personal. What started with Maratha queen Ahilyabai Holkar (1725-1795) inviting master karigars from Surat and Malwa to weave traditional nauvaris, became a thing of the past after Independence with the abolition of the privy purse and the rise of power looms. But when her descendent Shivajirao Richard Holkar and his then wife Sally, decided to give it a fillip in the 1970s with the founding of Rehwa, they ended up resuscitating the local textile industry, making Maheshwar one of India’s key weaving clusters.

Like with all pioneers, Rehwa and Sally have inspired those around them, spawning socially-conscious micro-labels, such as Amba. Launched in 1999 by American-born, Mumbai-based self-taught textile practitioner Hema Shroff Patel, it produces hand-woven super-fine natural dye scarves, stoles and block-printed djellabas that sell at trunk shows and select stores across the US, UK and France. Honouring traditional textile techniques while experimenting with yarn to create a design language that’s so very present-day, Hema seems to have spent a large chunk of the last 30 years in R&D as it were, producing along the way collections with a practice firmly rooted in Maheshwar but inspired by the urban, including 1930s architecture. A blue fabric with a geometric pattern that her team worked on was inspired by the angular woodcut window frame detail of Ram Mahal, a residential building in Churchgate that’s part of the UNESCO-honoured Victorian Gothic and Art Deco Ensembles of Bombay.

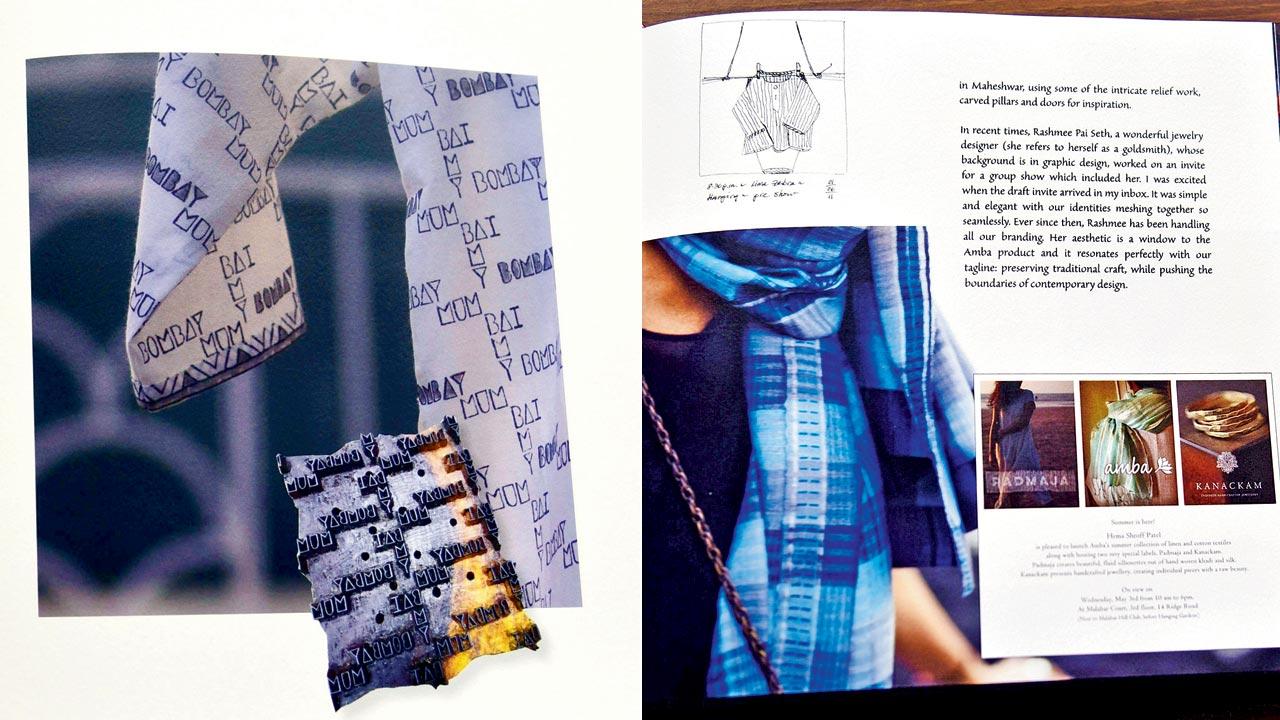

An innovative block print developed as an ode to the author’s city of residence; (right) The book carries the vibe of a journal with scribbled notes, sketches and photographs of swatches

An innovative block print developed as an ode to the author’s city of residence; (right) The book carries the vibe of a journal with scribbled notes, sketches and photographs of swatches

In her just-launched book, Amba Twenty-one Threads, Hema writes with candour about the hits and misses that make up the journey of a craft entrepreneur, which in her case, started with buying five metres of Rehwa-woven cotton to make kurta-pajama sets for kids that vividly showcased border details—a Maheshwari trademark. She dedicates a whole chapter to the relentless pursuit of natural dyes, failing and faltering before the team finds success at a Sawantwadi dyeing unit that does justice to Maheshwar’s unstarched degum silk easily given to tangling.

The tell-a-story style of her narrative mentions sundry collaborators she meets along the way, making this an unintentioned little black book of unique indie voices committed to Indian handloom. Dehradun’s resident Japanese textile designer Chiaki Maki’s scarves and stoles are hand spun, naturally dyed and hand woven at a sustainable in-nature studio where dyeing effluents reach directly down to the nearby indigo plantation. Andheri resident and Adiv Pure Nature’s Rupa Trivedi, who remarkably like Hema, has no formal training in textiles, runs a dyeing and garments units where she makes colours from scratch using onion peel, pomegranate, marigold and coconut. The hand-dyed fabrics are turned into quilts and scarves for the European market. In an earlier interview to this newspaper, Trivedi, who uses discarded hibiscus and marigold from Prabhadevi’s Siddhivinayak temple, had said, “I was my best teacher”. Hema speaks fondly of the marigold petals-dyed ‘puja’ saree in cotton and silk with a gold chatai border on which Rehwa, Amba and Adiv had once jammed.

In the book, the river is as central a protagonist as the writer herself, much like she is in Maheshwar. Personified as “Narmada ji”, she’s everywhere; from the hand-painted signboard of Maa Narmada Kirana Shop near Pandharinath mandir to the ornate ‘lehar’ border on the classic saree whose crests and troughs mimic her robust ripples. For Hema, the sacred river is equally a harbinger of peace and a gateway to adventure. “As Garbharbhai expertly rowed us to the river,” she writes about her first boat ride across, “Sally called out to our group and asked if anyone would like to swim across. And just like that we were diving off the boat!”

Hema, who calls herself “a compulsive list maker”, has a penchant for documenting; this makes the book resemble a mood board in part, part journal. It carries her scribbling and delightful line sketches, with the scant use of water colours. One of these towards the end of the book is of a potted plant and what looks like a folding chair in the corner of a sparse room. It could be the interiors of Amba Niwas, a cerulean blue-window cottage she decided to rent for her long stays at Maheshwar in Ahilya Vihar Colony that houses some 35 weaver families. Despite her privilege, that Hema chose not to be an armchair craft activist (they have their merits too), folded up her sleeves and got her hands dirty in indigo, makes this the story of someone who the bunkars can call their own.

Amba Twenty-one Threads is for those earnestly curious about India’s hand-weaving legacy and what a startup founder looked and behaved like in pre-liberalisation India. And for those who care to pluck the day.

Perhaps it’s time to finally sign up for that swimming class I’ve been dodging. I don’t want to be twiddling my thumbs when someone asks, “Would you like

to jump?”

To check out a copy of Amba Twenty-one Threads, DM @ambaweave

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!