Pune-based artist, Aditi Deo, is researching the ancient Indian Brahmi script to bring it into mainstream art and lettering, and fashion a children’s book on how shapes turn into sounds

Pune-based artist Aditi Deo is cross-referencing lettering found on ancient artefacts to develop an alphabet chart for Brahmi

Aditi Deo was putting together a module on lettering in March, which sent her down a rabbit hole. The illustrationist teaches calligraphy to adults and children, and mainly works with the Latin script (like the one you are reading right now). She wondered why the Devanagari script was not treated with the same gravitas in calligraphy and lettering lessons, which devoted many pages to the germination, history and evolution of the Latin letters. Information about it is not popularised, and one has to go peering into history books or study Indology. “The history of Latin script can be traced back to 3000 BC, while that of Indian scripts start at 300 BC,” she says.

ADVERTISEMENT

Through the rabbit hole, she landed on the Brahmi script. “The origin of the Brahmi script is disputed. While some believe it has developed from Aramaic script (northern Semitic script), other say it evolved within the subcontinent. It does not have anything in common with the [yet undeciphered] script of the ancient Indus Valley civilisation, but bears commonality with the northern Semitic scripts [used for Aramaic],” says Deo over an online interview, “But Brahmi is written left to right, while the other is right to left. Brahmi was the progenitor of most scripts in the subcontinent: Devnagiri, Dravidian and even Tibetan. Its role is fleetingly mentioned in History class. I only found a few articles about it online, which more or less corroborated each other’s information.”

The wall of a stupa in Sarnath, Uttar Pradesh, where Gautam Buddha first taught his followers has inscriptions in Brahmi script. Pic/Getty Images

The wall of a stupa in Sarnath, Uttar Pradesh, where Gautam Buddha first taught his followers has inscriptions in Brahmi script. Pic/Getty Images

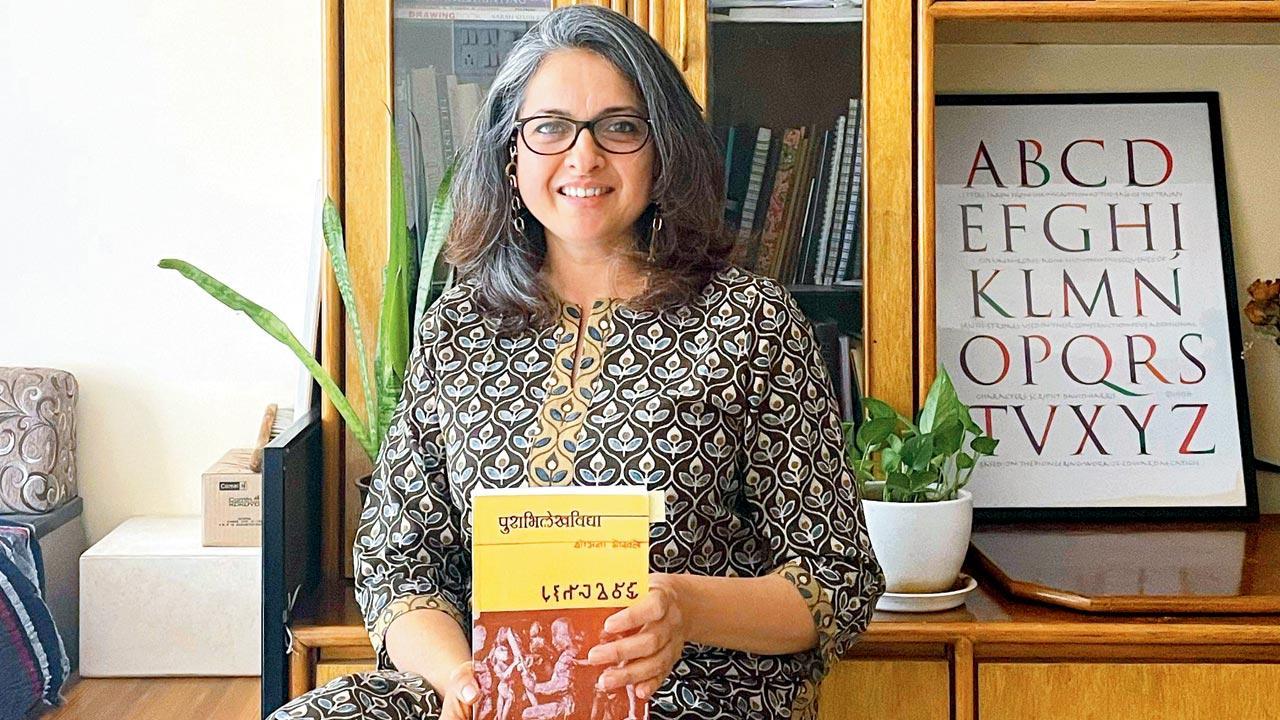

The first lead was Professor Manjiri Bhalerao who teaches ancient Indian scripts as part of the Indology course in Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth. She gave Deo a book called Purabhi Lekh Vidya by Shobhana Gokhale, roughly translating to ‘Knowledge of ancient scripts’. In it was a picture of a copperplate land deed dating to 415-420 CE, and it belonged to a family in Pune. “Suddenly, it was so close to home,” says Deo, who lives there.

“The book is in Marathi,” says the 48-year-old who runs The Doodle Factory, “so I am translating as I go.” The letters are shapes corresponding to sounds, with no baseline on top—a distinguishing trait in Devnagiri.

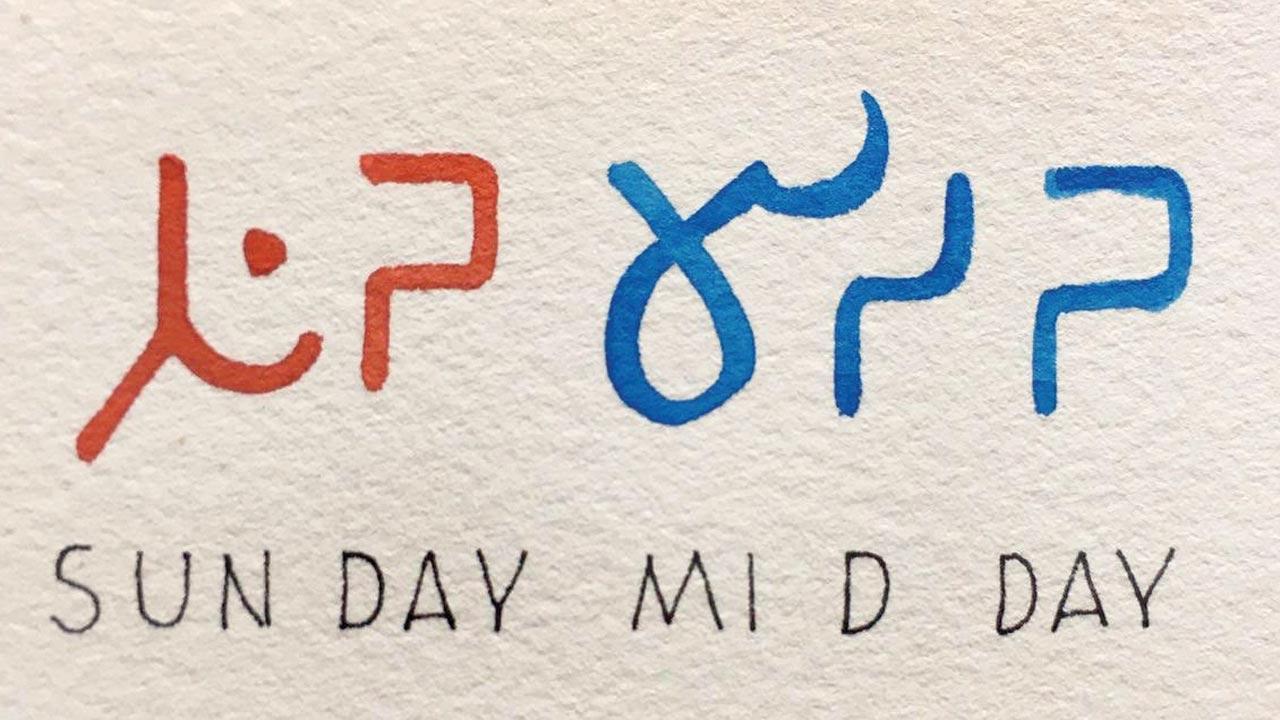

Sunday mid-day written in Brahmi. Some say the ancient script was influenced by the northern Semitic script, while others say it grew purely within the subcontinent

Sunday mid-day written in Brahmi. Some say the ancient script was influenced by the northern Semitic script, while others say it grew purely within the subcontinent

By cross-referencing lettering found on other ancient artefacts featured in the book, Deo is a working on an alphabet chart, which will evolve into a children’s book on how shapes turn into sounds. “I want to create multiple rabbit holes, even if only 5 per cent of the children go down it. Scripts are a kind of coding, which has a fun element. Also, it’s good to know or research something without tying it down to making lots of money from it,” she adds wryly.

An important distinction is to separate script from language. For instance, you could write the language Marathi in Latin script (and many Indianised words like that have made it to the Oxford dictionary) or in Devnagiri. And so it goes with Sanskrit.

“Literacy seems like a fairly recent concept to me,” says Deo, “The oral tradition was strong—languages such as Sanskrit were left undiluted because they were taught through recitation and repetition. Scripts started showing up on coins and royal edicts first because there was a need to say ‘this is the value of this coin, made under the rule of so-and-s0’ or ‘Alexander of Macedonia has conquered this area’ or ‘You are all Romans now’. The hieroglyphics in Egypt glorify the dead and their deeds. There was no reason for commoners to write anything down.” Then it moved on to royal priests, who needed to write down important matters pertaining to the rule of the king.

Deo conjectures that literacy became more important as kingdoms traded with or invaded each other. “You would need to claim land, spread ideology, or to be identified, as in the case of Alexander. King Ashoka’s edicts found near Bhubaneswar talk about Buddhism and what to aspire to,” she says.

In rudimentary scripts, called Abjad, only the consonants were written down with vowels to be filled in by the reader. Much like texting on a mobile phone before the advent of predictive text. “But in Brahmi, a vowel sound was attached with the consonant to make a unit,” she says.

Writing things down was a dynamic force. By 8 CE, Brahmi started splitting up and adapting to regional languages. “The act of writing it down also nudged the shape. It could be influenced by the handwriting or the medium, which required a slight alteration to be clearly read. By 11 to 12 CE, there were distinct scripts dedicated for regional languages.”

A symbol represented an object which then stood for a sound and thus evolved language. For instance, the letter ‘A’ started life upside down to denote a bull, then it turned right into a sort of ‘K’ and is now upright denoting the sound ‘Aa’ and is called the Alep in Semitic scripts. Devanagari’s unique top baseline also seems to have evolved later; Brahmi does not have it. “I remember my grandfather would draw the baseline first, from one end of the page to the other, and then write in Marathi, leaving gaps between words,” Says Deo. “By the time we wrote Marathi, the baseline held only one word together.”

She hopes to take children on this journey of shape-shifting scripts in her children’s book. But there is more research before that… “I have to trace how the Dravidian script changed so drastically,” says the artist.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!