Before India’s second museum dedicated to 1947’s Partition of South Asia opens up for the public, founder Kishwar Desai conducts a special walk-through for Sunday mid-Day and a writer trying to find her place between ancestral Lahore and her city of residence

The museum’s lobby-area leading up to the exhibition opens with the Kashmiri papier mache sculpture of a horse carrying a load of skulls and bones by Kashmiri artist Veer Munshi. Pics/Nishad Alam

At a hectic and continuous intersection of history from 17th to 21st century Delhi, facing the Delhi Junction Railway Station, an ancient building inside Ambedkar University is readying for its latest life as a museum. Its first stint was as Mughal prince Dara Shikoh’s library. It will now hold the country’s second Partition Museum dedicated to the 1947 Partition of South Asia into India and (East and West) Pakistan by the British Imperial rule.

ADVERTISEMENT

“This museum has a strong Delhi focus,” says Kishwar Desai, author and chairperson of The Arts and Cultural Heritage Trust (TACHT) that has founded both museums. The Delhi Partition Museum’s building was given to them by the Union Government’s Adopt A Heritage scheme, and was restored by the Delhi Government. The curatorial team comprises Desai, Mallika Ahluwalia, Ganeev Dhillon, Shreyashi Bagchi and Himanshi Saini.

The ancient building inside Ambedkar University was once Mughal prince Dara Shikoh’s library and is now set to hold the country’s second Partition Museum dedicated to the 1947 Partition of South Asia into India and (East and West) Pakistan by the British Imperial rule

The ancient building inside Ambedkar University was once Mughal prince Dara Shikoh’s library and is now set to hold the country’s second Partition Museum dedicated to the 1947 Partition of South Asia into India and (East and West) Pakistan by the British Imperial rule

The other museum is located in Town Hall building of Punjab’s Amritsar city, that my ancestors travelled to without fuss, from its erstwhile twin-city Lahore.

These cities are still an hour’s drive apart, but bureaucratic miles away due to the Partition’s creation of the India-Pakistan Wagah-Attari border. It’s these distances that the museums—possibly the only ones dedicated to one of 20th century’s largest human migrations—hope to understand and reconcile with.

That’s what I went for too: to know my place in this history. After all, I live in Delhi, the ‘Punjabi refugee city’ and not in my paternal-ancestral Lahore, casually passing Mughal queen Nur Jahan’s tomb, mouthing the Farsi verse inscribed on it that’s part of my inherited memory of home.

Between the Migration and Refuge galleries, sits the simulation of a train coach symbolising the transport that became synonymous with the sights of numerous Partition-migration massacres

Between the Migration and Refuge galleries, sits the simulation of a train coach symbolising the transport that became synonymous with the sights of numerous Partition-migration massacres

Nor do I spend summers eating the glowing-yellow berries of the khirnee tree in my grandparents’ home of a now-untraceable village in Pakistan’s Jhang province.

The museum’s lobby-area leads up to the exhibition, opening with a sculpture of a horse made of Kashmiri papier-mâché. I walked closer to inspect the horse’s load and was instantly horrified: it’s all skulls and bones. The metaphor of Kashmir, still bearing Partition’s festering wound, isn’t lost on me.

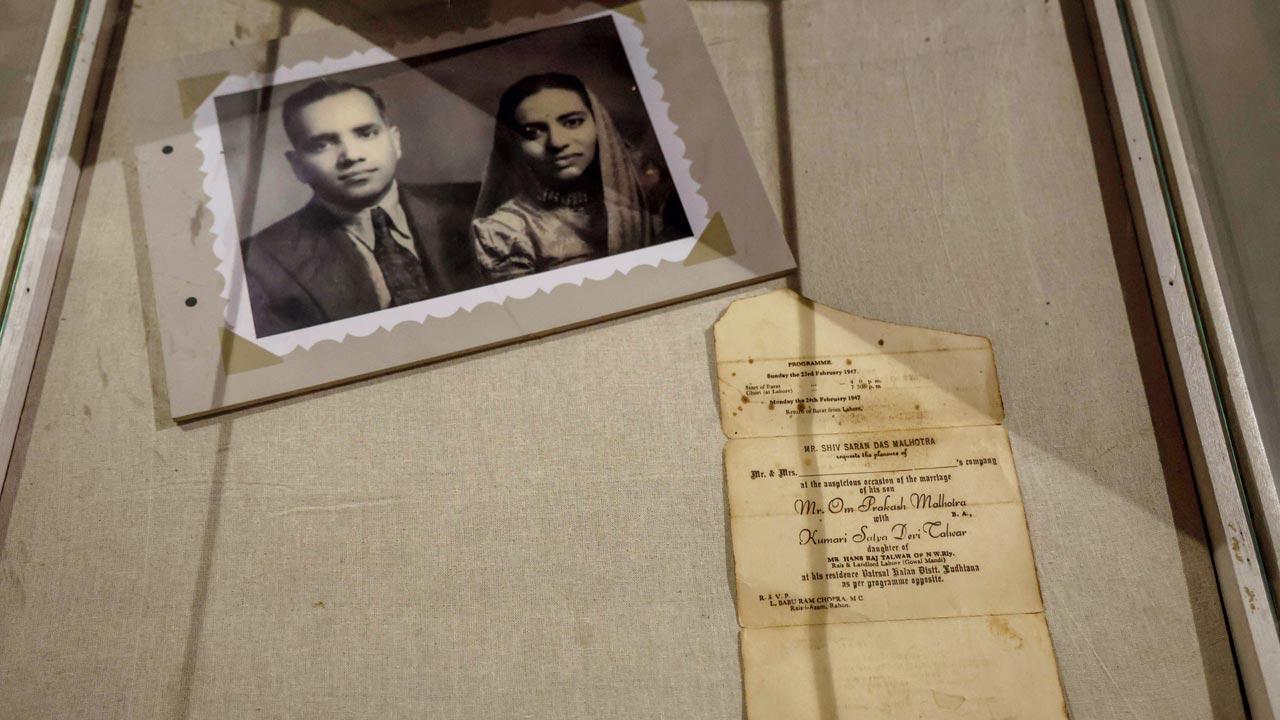

An invite to a wedding in Lahore scheduled for Sunday, February 23, 1947. The text-brief alongside claims it to be ‘The Last Peaceful Wedding of Lahore’

An invite to a wedding in Lahore scheduled for Sunday, February 23, 1947. The text-brief alongside claims it to be ‘The Last Peaceful Wedding of Lahore’

The walls have giant portraits of Hindu, Muslim, and Anglo-Indian Christian residents of old Delhi who stayed put and also provided refuge to many despite the communal violence that forced millions to become refugees in their own lands. Our people’s real-life Amar, Akbar, Anthony sentiment.

I walk into the actual opening of the exhibition along a blown-up black-and-white image of American photographer Margaret Bourke-White’s work, ubiquitous in all Google-search results of Partition’s photos.

Kishwar Desai, author and chairperson of The Arts and Cultural Heritage Trust (TACHT) that has founded both museums

Kishwar Desai, author and chairperson of The Arts and Cultural Heritage Trust (TACHT) that has founded both museums

The galleries ahead are divided by themes of chronology: Independence and Partition, Migration (extending to photographs of riots and Partition in the mind of 20th century’s greatest Indian artists), Refuge, Rebuilding Home, Rebuilding Relationships, and Hope & Courage.

A continuous projection of newspaper headlines from that subcontinent-defining era is around me. There’s the jubilance of Independence to Pakistan and India, there’s caution (the British regime had successfully divided people communally by then); and the havoc of redrawing boundaries, the Radcliffe Line, announced on August 17, 1947.

Old Delhi’s Partition survivors reminisce about the area’s communal harmony despite widespread rioting elsewhere

Old Delhi’s Partition survivors reminisce about the area’s communal harmony despite widespread rioting elsewhere

The gallery on Independence and Partition is a busy mass of walls with reproductions of historical pamphlets, posters, newspaper-clippings, photographs, maps, etc., starting from the year 1942 and until 1947, a decisive leg in the expulsion of the British regime from South Asia, the World War II and intense freedom agitations in India.

The chronology and the information became too intense to follow, and I gravitated towards an exhibit in a glass-case. It was a micro-history wedded to mine—an invite to a wedding in Lahore scheduled for Sunday, February 23, 1947. The text-brief alongside claims it to be ‘The Last Peaceful Wedding of Lahore,’ an anecdotal history of this family of the city’s landed rich as matter-of-fact history; the Rawalpindi Massacres of March 1947 might have had that awful effect on communal coexistence.

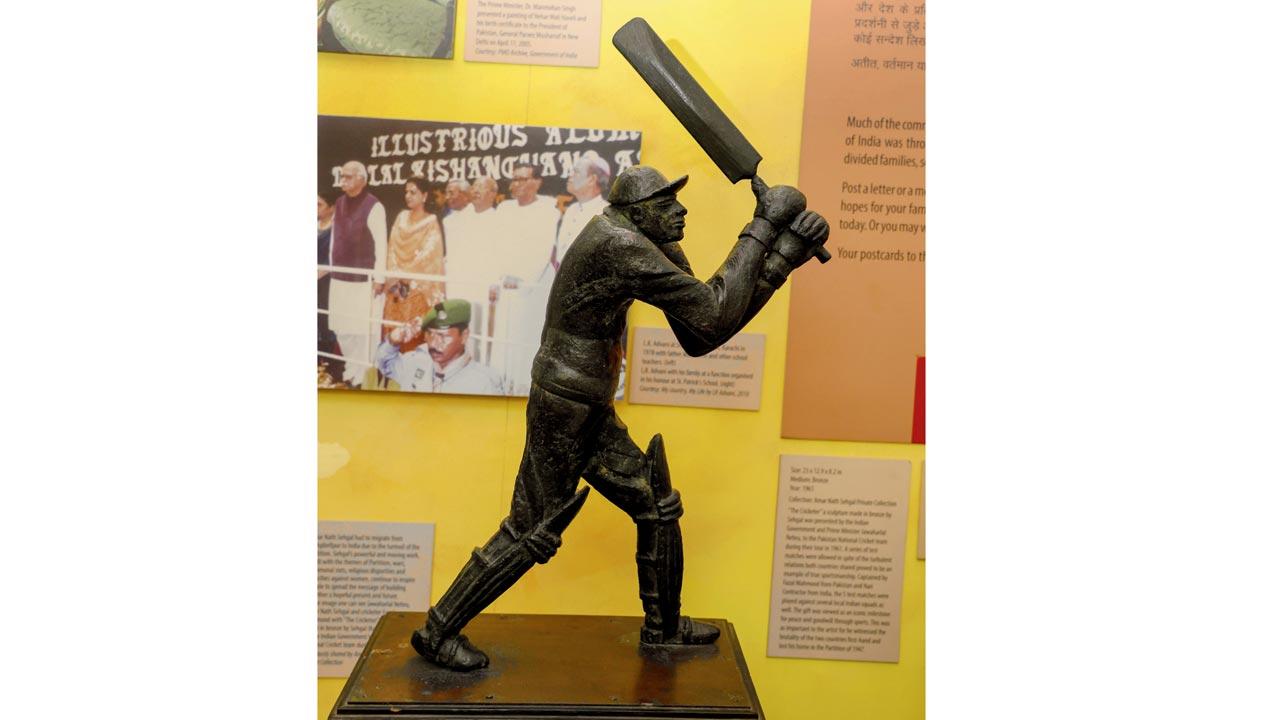

The Cricketer by sculptor Amar Nath Sehgal of a cricketer just after taking a shot. In 1961, then PM Nehru had gifted the older of this statue-pair to Pakistan’s cricket team on their India tour. That statue of The Cricketer still lives in Pakistan

The Cricketer by sculptor Amar Nath Sehgal of a cricketer just after taking a shot. In 1961, then PM Nehru had gifted the older of this statue-pair to Pakistan’s cricket team on their India tour. That statue of The Cricketer still lives in Pakistan

Personal belongings like this card are among the donations to this “people’s museum” that’s entirely founded by private donations in money, oral and material histories gathered from “500-600 people and their families” by TACHT.

A few of the galleries are consequently dedicated to people from India’s most influential households and industrial empires.

It is also a dismal reminder that whose histories are most diligently documented, preserved, and repeated depends on predictable markers of caste, religion and class, even though the museum dedicates the small section of a wall to the Dalit experience of Partition.

I glanced back at the wedding card: the hosts are the “Rais (rich and noble) and Landlord of Lahore” and the title Rais-i-Azam, the greatest of the rich was also there.

This induced an introspection for me: the contrasting social locations of my paternal and maternal families. The family situated pre-Partition in a cosmopolitan city and in government jobs, migrated via train, has letters, degrees, records, keepsakes from their homeland. Parts of it launched itself into America and elsewhere after migration.

The other side of the family living pre-partition in a village, migrated empty-handed via bullock cart and only few members in its third generation after Partition afforded comparable economic migration to foreign countries. Despite these contrasts, my heritage is one of a cultural Hindu’s uber-privilege in holding the luxury to pore over, grieve, and understand this violent history of my people.

The galleries ahead are a predictable confluence of historical visuals on walls and personal objects in glass cases. Each room also has at least one screen playing videos of survivors narrating oral histories or a prominent historical commentator explaining the complex Colonial history. There is almost a rhythmic alternation of historical rigour with a slightly-loose oral history placed on equal footing. This can be jarring to puritans and a welcome relief from oppressive, overwhelming details for those preferring more whimsical history lessons.

I wanted to quickly pass from the gallery on Migration to the gallery of Refuge. For this, I had to cross the simulation of a train coach. Trains were the sights of numerous Partition-migration massacres I’d read about in novels, watched in films, and heard from ancestors.

I was relieved to realise I’m still not desensitised to the sights of the horrific mass-migration from 75 years ago.

The Refuge gallery was not a comforting sight, nor new. Familiar picnic-spots of Delhi’s Puraana Qila and Humayun’s Tomb flooded with refugee tents in 1947 and the following years.

In 2018, I had reported about the government-sanctioned demolition of a Partition-era school-building inside the Puraana Qila. I was pained to think of that relic being stolen from refugees who used to visit with their children and grandchildren until the now-defunct school’s demolition. This museum, even if 75 years after the events, may at least offer some balm and catharsis.

I noticed the hint of a Mohammad Rafi song from somewhere, so my feet were hypnotised to move towards it. The song-source grew closer. I was now watching my city, my own rental neighbourhood, my older neighbourhoods, familiar roads, hospitals, colleges, from their birth-era. Rebuilding Home is a hopeful gallery.

Its exhibits symbolise the unbreakable spirits that gave a new identity to India’s capital city: a sewing machine, the vehicle of independent economic sustenance that countless women and girls used after surviving sexual violence, loss of all earning, male relatives; commemorative tools that were used to lay foundation of Punjabi Bagh by then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, telling the residents to not call themselves refugees, but Punjabis of Punjabi Bagh.

Similar nostalgic affirmations and hat-tips to lost homelands are still common in the names of Delhi’s neighbourhoods and establishments: Gujranwala Town, Mianwali Nagar, Rawalpindi Jewellers, Multan Nagar, Sindhi Kulfi, Derawal Nagar, Dera Ismail Khan BS School.

Now, I heard Rafi clearly while moving to Rebuilding Relationships gallery. I recognised the tune, of course! I’ve grown up on Yash Chopra’s cinema. “Tu Hindu banega, na Musalmaan banega, insaan ki aulaad hai insaan banega, you won’t become Hindu or Muslim, you’re the child of a human and will become just that.”

Chopra, himself a Partition-migrant, used this Sahir Ludhianvi lyric in his 1959’s directorial debut Dhool Ka Phool, long before millennials like I were born. But it’s the spirit of such popular culture even till 21st century’s Bollywood-blockbuster Veer-Zaara, a cross-border love-story by Chopra, that reminds us we are one people divided by Colonial borders and self-serving politicians.

This gallery is studded with posters of a sample of such film and TV productions from India: Waqt, Garm Hava, Tamas, Pinjar, Earth.

A contemporary, emotive virtual-reality film Child of Empire, is also available for viewing here. An entire wall celebrates Partition writers like Sadat Hasan Manto, Krishna Sobti, Khushwant Singh, and others.

It’s this hope we carry into the final, gallery of Hope & Courage, where one can post a postcard to the past or to the future into a real letter-box. Some of these postcards, including those written by Pakistanis, during a Partition Museum initiative, are on display at a board.

Alongside, an iconic, bronze sculpture, The Cricketer, by sculptor Amar Nath Sehgal, of a cricketer just after taking a shot, drills in India-Pakistan’s similarities in their collective obsession for cricket. In 1961, then PM Nehru had gifted the older of this statue-pair—of a batsman ready to hit a ball—to Pakistan’s cricket team on their India tour. That statue of The Cricketer still lives in Pakistan. A brother here, a brother there.

I had a sombre flashback of witnessing my friend’s old Delhi father and his elder brother, who had moved to Pakistan during Partition, having a tearful reunion after their entire youth apart. The friend’s uncle had managed to secure a visa with much difficulty to attend her wedding in Delhi. The brothers were sadder to not know when they’d meet next at their childhood home.

“Because of my father’s connections on the other side [Pakistan] as a young police officer in Amritsar, he was able to arrange a meeting between Madam Noor Jahan and Lata Mangeshkar on the border!” says Desai. Her Partition-migrant father was among the first IPS cadre of independent India. Noor Jahan had brought along kebabs from Lahore and our greatest singing sensations had picnicked at the border, she recounts this oral history playable in the museum.

“But in those days, it was a soft border because people knew each other.” How long can a border stay hard-hearted towards a shared melody, though?

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!