Between the culinary treasures of Bhendi Bazaar lies an aesthetic treat — the workshop that creates contemporary Ajrakh that international designers lap up

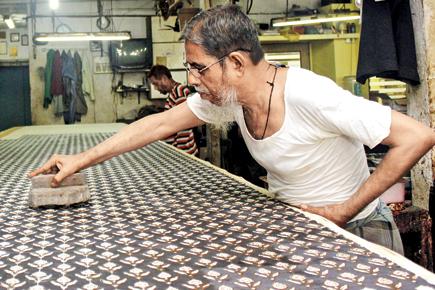

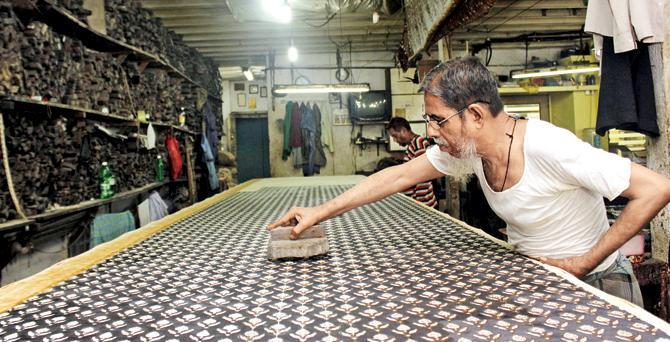

Ahmed and Sarfraz Khatriu00c3u00a2u00c2u0080u00c2u0099s block-printing workshop at Bhendi Bazaar.

ADVERTISEMENT

Picture this: American fashion designer Donna Karan treks her way through the serpentine maze that makes up the trade village squatting between Masjid Bunder station and Mohammed Ali Road. At an industrial estate in Damar Galli, she walks up the vertiginous stairs to the penultimate floor and opens the door to something like Aladdin’s den.

Only, instead of gold coins and ornaments, the antechamber is filled with fabrics dyed with natural dyes — dupoin silks, 200 gm crepe de chines, georgette tussar, and wool and silk blends. The inner chamber is a workshop with long work benches where bent men with inked fingers rhythmically keep time with a double-tap that transfers print on cloth.

Ahmed and Sarfraz Khatri’s block-printing workshop at Bhendi Bazaar. Pics/Tushar SatamAM

For a designer, Ahmed and Sarfraz Khatri’s workshop is a gold mine. Donna Karan did visit here in 2013 and bought R5 lakh worth of fabric for a collection. She’s not the only one. Rohit Bal, Priyadarshini Rao and many others who would rather not say that their unique prints, made from eco-friendly dyes come from this 25-year-old workshop in the heart of Mumbai and not in the scenic deserts of Kutch.

Though the Khatris are from the region of Kutch, Pracheen’s tale is not one of painstakingly hanging on to a hereditary craft. Ahmed Khatri was a synthetic dyer, working in a business built by his father. In the early 90s, a customer asked Ahmed to try his hand at natural dyes. “I made my way to Nissar Sikander,” says Ahmed, the senior Khatri, “a supplier who lived in Jogeshwari, who told me the process verbally. I bought 100 gms of ingredients from him — henna for mustard, madder for red, indigo, limestone for resist and went home to experiment. I went back to him with a few samples and he said I should stick to this method as it would take me far.”

Ahmed was familiar with Ajrakh, a 13-step printing technique, originating in the Sindh and Kutch region, since that’s where the family is from. On a trip to the region as a 13-year-old he had bought blocks with his father. “My father had a usool,” says 56-year-old Ahmed, “Never sell the blocks — you can give them away for free.” As a result, the family has a library of more than 800 blocks which are close to 80 years old — with new designs carved often. “The olden brass blocks have a very fine print which cannot be replicated anymore,” says 36-year-old Sarfraz, Ahmed’s son.

Ahmed Khatri’s family hails from Kutch, where the tradition of Ajrakh originated

Ahmed Khatri’s family hails from Kutch, where the tradition of Ajrakh originated

He started hanging out at the workshop after school when he was in class 10, and played around with the blocks and dyes. Meanwhile, Ahmed’s business was growing due to word-of-mouth. “In 1995, I was invited to showcase at a symposium in Delhi,” says Ahmed. “A student from National Institute of Design (NID) came and stayed with us for 10 days and gave us some guidelines. We made 60 pieces which were sold out in the first hour. For the first time in my life, I saw Rs 1.5 lakh in cash!”

Meanwhile, Nissar Sikandar’s wife, an artist, sent a silk dupatta with a leaf pattern created by Ahmed to the committee that oversees national awards for craftsmen. The piece won Ahmed the award in 2005. With Sarfraz’s growing interest in the trade, Ahmed sent him to apprentice with Dr Ismail Khatri, who has an honorary degree for his craft and is also a National Award winner, in Ajrakhpur. Their pact was that Sarfraz would not mimic traditional Ajrakh patterns (Islamic and Mughal motifs), thus avoiding a clash of business interests with his mentor.

“We modernised prints and played with the design concepts, experimented with the intensity of the dyes and expanded the kind of natural cloth that can take the print,” says Sarfraz.

At his stall at the last Lakmé Fashion Week, Sarfraz displayed lush, thick crepe with an ink splatter design that looked like batik, but was block print. Vibrant reds with the finesse of screen printing, that also came from blocks. They retail through trade exhibitions such as Paramparik Karigar, and four stores across the country. “Due to the time taken for production, designers prefer buying ready stock and yardages,” says Sarfraz.

This production pace also keeps the fabric out of avenues of fast fashion. “If there were platforms like fashion week,” says Sarfraz, “where we can display current stocks for large scale buyers, we would be able to expand operations.” It would also grow a small workshop into a factory that provides sustained employment, and legitimise it as a provider of quality products, not a backdoor provider of raw material for luxury designers. Or, you could make the trek like Rohit Bal does to the cave in Bhendi Bazaar.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!